How did King Tut really die?

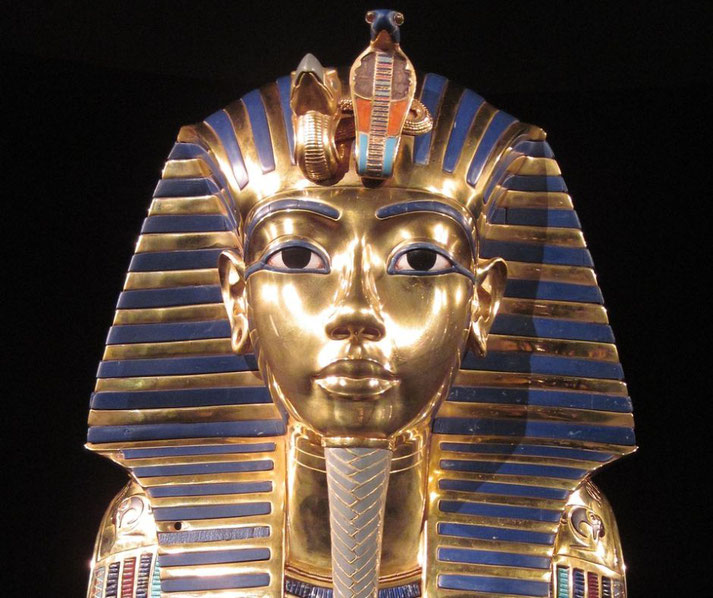

When the tomb of King Tutankhamun was found by Howard Carter in 1922, it held a treasure trove of mysteries.

The Boy King had ruled during a time of great change in ancient Egypt, but his sudden death continued to puzzle historians and scientists alike.

After more than a century of research and debate, experts still are still uncovering clues about what led to his death.

What do we know about Tutankhamun, the ‘boy king’?

Tutankhamun ascended to the throne of Egypt at around the age of nine.

During his short reign, from 1332 to 1323 BCE, Tutankhamun worked to end the worship of Aten and restore the polytheistic religious practices his father, Akhenaten, had altered.

With the help of his advisors Ay and Horemheb, Tutankhamun brought stability to the kingdom and his marriage to his half-sister Ankhesenamun strengthened his position as pharaoh.

By repairing temples and supporting the old gods, Tutankhamun sought to restore the glory of earlier dynasties.

At the same time, he moved the capital back to Thebes from Akhetaten. His reign lasted only about ten years when he died unexpectedly.

After his mysterious death, Tutankhamun’s tomb remained undisturbed for centuries.

Unlike other pharaohs whose tombs were looted, his burial site stayed hidden beneath layers of debris until the early 20th century.

The sensational discovery of his tomb

In November 1922, Howard Carter made one of the most notable archaeological finds of the 20th century.

In the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor, he uncovered the tomb of Tutankhamun.

For years Carter had searched for the pharaoh’s burial site. With financial backing from Lord Carnarvon, who shared his interest in Egyptology, he conducted a number of excavations but always came up short of finding what he was really after.

On November 4, a worker found a stone step leading to the tomb’s entrance.

Upon entering, Carter and his team discovered an undisturbed royal burial site.

The first chamber held an impressive array of artifacts, including chariots, furniture, and statues.

They immediately recognized the importance of their discovery.

By November 26, Carter peered through a small hole in the doorway and said he saw “wonderful things,” referring to the antechamber objects.

The nested coffins within the burial chamber, including Tutankhamun’s intact sarcophagus, would not be revealed until January 1923 when the inner chamber was opened.

As the team catalogued each item, the collection astonished the world. With over 5,000 items, the discovery stood unmatched in its richness.

Was King Tut murdered?

Once Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun's tomb, the young pharaoh's cause of death became a subject of great speculation.

Early theories suggested that Tutankhamun might have been deliberately murdered.

At the time of his death, Tutankhamun was a young pharaoh who had reversed many policies of his predecessor, Akhenaten.

This might have pushed away powerful groups within the priesthood and military.

Such groups had strong interests in keeping or regaining their influence. As a result, he might have created enemies among the powerful elite.

Specifically, the roles of key figures such as Ay and Horemheb came under scrutiny.

Since Ay had served as a powerful advisor during Tutankhamun’s reign and would succeed him as pharaoh, he had much to gain from the pharaoh’s death.

Similarly, Horemheb, commander of the army, might have harbored ambitions that included removing the young king.

Tutankhamun’s early death left no clear successor, allowing these two powerful figures to compete for control.

In the 1960s, radiologist R. G. Harrison conducted the first X-ray analysis of Tutankhamun’s mummy, and he found a thick area at the base of the skull originally thought to be evidence of a fatal blow.

Then, in 2005, a team led by Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass conducted a detailed CT scan of the pharaoh’s mummy.

Those scans revealed that the skull damage occurred after death and was probably caused by Carter’s handling of the mummy during excavation.

Was it simply an accident?

When Howard Carter discovered the tomb, initial examinations focused on the visible injuries and the condition of the body.

The most notable finding was a fracture in the middle of the left femur, but little more was concluded at that stage.

By the 1970s, interest in solving the mystery of Tutankhamun’s death had grown and some researchers suggested that the young king might have died from an infection caused by that broken leg.

Since healing was absent around the injury, it showed that Tutankhamun likely died shortly after sustaining it.

Experts concluded from the type of the break that it might have resulted from a serious accident, such as falling from a chariot.

In ancient Egypt, chariots played important roles in both military and ceremonial contexts.

As a pharaoh, Tutankhamun would have ridden chariots frequently.

Similarly, the scans showed an unusually small and broken navicular bone in his left foot, which some scholars called Köhler disease II (navicular osteochondrosis).

Other researchers suggested that the irregularity might have come from congenital underdevelopment or a clubfoot deformity instead.

Evidence of chronic foot pain in a royal setting appeared in the form of dozens walking sticks found among his funerary belongings, which suggested limited mobility in his final years.

Health issues of this kind probably increased the risk of an accident.

Was Tutankhamun seriously ill?

More recently, researchers suggested that Tutankhamun died from a combination of diseases and inherited disorders.

Advances in technology allowed scientists to study his mummy in great detail. In 2010, DNA analysis found fragments of Plasmodium falciparum in his remains, which meant that he had contracted malaria at least once.

But this did not prove whether those infections were severe enough by themselves to threaten his life.

The 2005 CT scans also revealed a gap in the hard palate that some specialists saw as a cleft palate; other experts argued that this might be damage that occurred after death rather than a birth defect.

The same scans showed a slight bend in his spine, a mild spinal curve according to some but not necessarily meeting the clinical criteria for true scoliosis.

Overall, the combined observations painted a picture of a young pharaoh whose physical condition was fragile.

How inbreeding may have doomed the boy king

Despite royal advantages, he faced ongoing health problems that likely weakened him.

Genetic analysis also confirmed that Tutankhamun’s parents were closely related.

His father was Akhenaten, and his mother was the mummy known as the “Younger Lady” from tomb KV35, widely believed to have been Akhenaten’s sister.

An incestuous marriage common among Egyptian royalty to keep the bloodline pure increased the chance of inherited disorders.

As a result, inherited factors seemed to have contributed to his palate issue and spinal curve, though the exact genetic causes were not clear.

That said, the question of murder remained open. No contemporary record or archaeological proof showed foul play, but his many health problems made him an easier target in theory.

Rivals seeking power might have used his frailty to their advantage. In a society where royal succession often led to conflict, removing a physically weak pharaoh offered a chance to advance.

Yet this idea was based on speculation rather than on firm evidence.

The real cause of Tutankhamun’s death?

Ultimately, Tutankhamun's death likely resulted from a combination of several debilitating factors. His genetic background meant that his body was already compromised.

So, when suffering recurrent bouts of malaria, his body faced constant strain and made him highly vulnerable to additional health complications.

As a result, when he suffered the fracture in his left thigh bone, with a compromised immune system, his body would have genuinely struggled to heal the wound and even a minor initial infection could have become fatal.

On the other hand, it wouldn't take much for an assassination to exploit Tutankhamun's fragile condition. His numerous health issues already placed him in a vulnerable state, and even a minor attack could have catastrophic consequences.

By removing Tutankhamun, they stood to gain power and control over the kingdom.

In a society where royal succession was often contested, assassinating a weak and ailing pharaoh would have been an opportunistic move.

The lack of conclusive evidence of a specific cause of death leaves room for speculation.

While modern analyses have debunked some earlier theories, they have not entirely ruled out assassination.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.