Ancient Chinese social structure explained

Ancient Chinese society was incredibly structured, with each person knowing exactly where they sat on the social hierarchy.

As early as the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046 to 256 BC), all of the people in China were assigned to one of four social groups, also known as social ‘classes’.

In Chinese, these groups were called the shi, nong, gong, and shang. Each of these is explained in more detail below.

While it was technically possible for a person to move from one social class to another, it was highly unlikely for most people.

Only through lucky circumstances or marrying into a higher social group could people hope to progress up the hierarchy.

For the majority of people, the class they were born into was the social group they remained in for their entire lives.

Social Structure

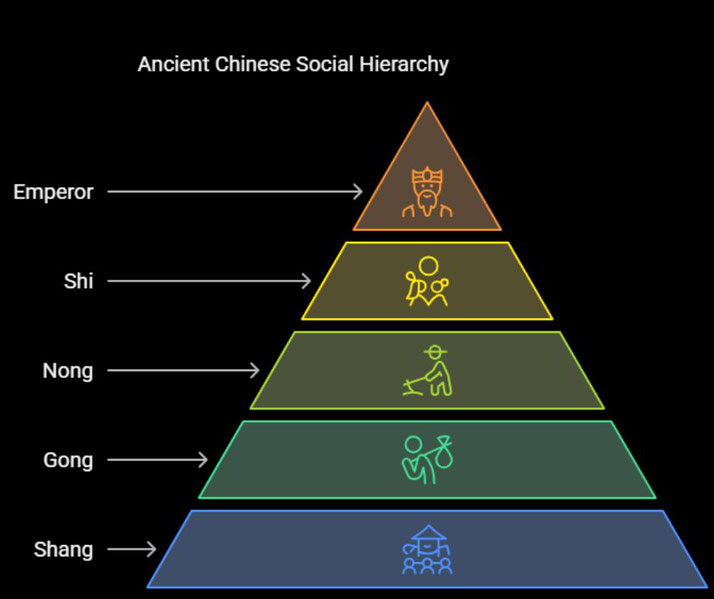

China’s social structure was based upon the idea of ‘four occupations’. Each social group was classified by the jobs the men in that class did on a daily basis, and the services they provided to the Chinese kingdom.

The four classes sat underneath the emperor, who was at the top of Chinese society.

It can be visualized like this:

1. The Shi (Nobles, scholars, and officials)

This social group was the ruling class and was at the top of the social scale. They held most of the power in society.

The shi class was made up of the governors of the regions of China, such as Zhao, Qin and Wei. Most of these governors were regional warlords.

These military commanders held an incredible amount of power, particularly during the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC to 1046 BC).

Many tombs from this period have been uncovered that contain powerful war chariots and the remains of thousands of followers buried with their masters.

The second kind of person in the shi class were the land-owning nobles. Those in this social group gained their power through inheriting land, power and status from being born into the noble families.

The nobles were required to raise armies for the governors and act as battlefield commanders during war time.

Obviously, the soldiers who were forced into these armies came from the peasant class.

The final kind of people in this group were the scholars: men who had spent their life studying in order to work as bureaucrats in the imperial government.

The scholars did not own land, but they were treated with great respect because they were very knowledgeable and were able to read and write.

The people in the shi class exerted their authority over the rest of the social classes below them, which was most of ancient Chinese society.

2. The Nong (Peasant farmers)

The people in the nong social class made up the vast majority of Chinese society: perhaps as much as 90%.

These people were peasants who lived in small rural communities whose main job was to work on the farms throughout China.

However, the farms were all owned by members of the shi class, and the peasants were required to work their fields in return for military protection.

Agriculture was the most important part of ancient Chinese economy and the more crops that peasants grew, the richer their masters would be.

The peasants could be tasked with raising sheep, pigs, poultry, buffalo and oxen, or growing grains such as wheat, millet and barley.

As a result, the people of the nong class produced all of the food for the country and they paid most of the taxes.

Therefore, they were considered to be a very important part of Chinese society and were positioned above the two other social classes for this reason.

However, most of the people in the nong group were powerless to change their lives, and most of them remained relatively poor throughout Chinese history.

Most peasants only had one or two hectares of land to look after and to draw an income from, which was often barely enough to avoid going into debt.

Unfortunately, during times of drought, war or economic difficulties, peasants often faced starvation, and evidence shows that some peasant families were forced to sell their children into slavery just to survive.

When their lords needed to raise armies for war, the peasants were recruited to create infantry units.

Their main job was to engage in hand-to-hand fighting with other peasants who were conscripted in the opposite army.

As is to be expected, most deaths on a battlefield were among the peasants, and if they were captured by the enemy, they were often executed or sold into slavery.

However, as difficult as life as a peasant in ancient Chinese society must have been, there were two more social classes lower on the social hierarchy.

3. The Gong (Artisans and craftspeople)

The third social class in ancient Chinese society was made up of artisans and craftspeople.

The people in this group had particular skills required to make highly specialised items. Included in this group were armourers, metalworkers, and carpenters.

The number of people in the gong social class was much smaller than that of the peasants, since learning these skills took time, which most peasants did not have.

However, unlike the peasants, craftspeople did not work on any land, and since agriculture and land ownership were so central to ancient China, their activities did not generate as much revenue as farming.

As a result, craftspeople were treated as ‘inferior’ to nong class.

However, despite being technically lower on the social scale than the peasants and nobles, artisans and craftspeople made the products that everyone else used in daily life.

For example, most household objects were made of some form of pottery, and as a result, most people were reliant upon potters throughout ancient China.

Their skills were so highly valued that families usually kept them a carefully guarded secret and passed them down from one generation to another.

Some artisans and craftspeople were even able to build businesses that hired other people to work for them.

4. The Shang (Merchants and traders)

The fourth and final social class in ancient Chinese society was made up of merchants and traders.

The members of the shang group focused on making money by selling objects to other people.

The reason that the merchants were placed at the bottom of the social structure in ancient China, is that they did not make anything of their own.

Unlike the peasants, who made food through their own hard work, or the craftspeople, who made objects through their own effort, merchants simply bought items from one person and sold them to another.

This was considered to be ‘dishonourable’ and ‘lazy’.

However, despite being at the bottom of Chinese society, merchants could become incredibly wealthy.

Many made their money simply by lending money to those who were in debt, and then charging regular payments until the loan was paid back.

Other traders generated wealth by exporting expensive products, such as silk, to other kingdoms or countries.

Slaves

The only members of ancient Chinese society that were considered ‘less honourable’ than the merchants, were the slaves.

It is estimated that less than 1% of ancient Chinese society were slaves and were technically not included in the social hierarchy.

Most people became slaves either through being captured in war, or by selling themselves into slavery to pay off a family debt.

On some occasions, people were condemned to slavery as a punishment for committing a crime.

Slaves could be owned by a member of any of the social classes, as long as they could afford to buy and feed them.

However, most slaves worked for members of the shi class, since they were the ones who were wealthy enough to afford them.

What about the emperor?

You’ll notice that even though we’ve explored the four social classes in detail, we never mentioned the most powerful person in ancient Chinese society: the emperor.

While many people assume that he would be included in the highest social class, the shi, this is not actually true.

The emperor was considered to be the most important person in Chinese society because the was given the ‘mandate of heaven’, which placed him in a special position above everyone else in China.

Therefore, the emperor and the royal family were considered to be above every other social class.

This elevated position meant that the emperor and the royal family had direct control over everyone else.

All four social classes were expected to follow his commands without question, and the emperor could order the death of anyone in society whenever he chose.

As a result of these incredible powers, the emperor and the imperial family were treated with the utmost respect by everyone.

However, the emperor was expected to rule well. If China suffered a series of natural disasters or if they were losing wars against invaders, the rest of society could decide that the emperor had lost the ‘mandate of heaven’ and could overthrow him.

If an emperor was overthrown, there was always a new emperor put in his place who was told that they now had the ‘mandate of heaven’.

Women in Chinese society

You would have also noticed in our study of Chinese society that we haven’t specifically mentioned women.

The four social classes mentioned so far all applied equally to men and women.

However, ancient Chinese society believed that women were naturally inferior to men, and they were treated in this way in everyday life.

This tendency began at birth. Chinese families treated sons better than daughters, and during times of hardship, poor families might kill baby girls in order to have one less mouth to feed.

In contrast, women who lived in the wealthy shi class lived relatively privileged lives.

They would have access to the best food, entertainment, clothes, and various servants.

However, regardless of what social class they were part of, women were considered to be most valuable when they had given birth.

In particular, women were treated with the most respect when they had provided a son for their husband.

When girls were old enough to marry, young women were expected to live with her husband’s family.

This was because traditional Chinese society believed that a man had to take care of his elderly parents and it was his wife’s job to help him do that.

Women were therefore expected to not only obey their husband, but to also obey his mother and father.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.