Roman gladiators: Ancient professional athletes

Imagine stepping back in time to the days of ancient Rome, where the clash of swords and the roar of the crowd echo through the great stadium known as the Colosseum.

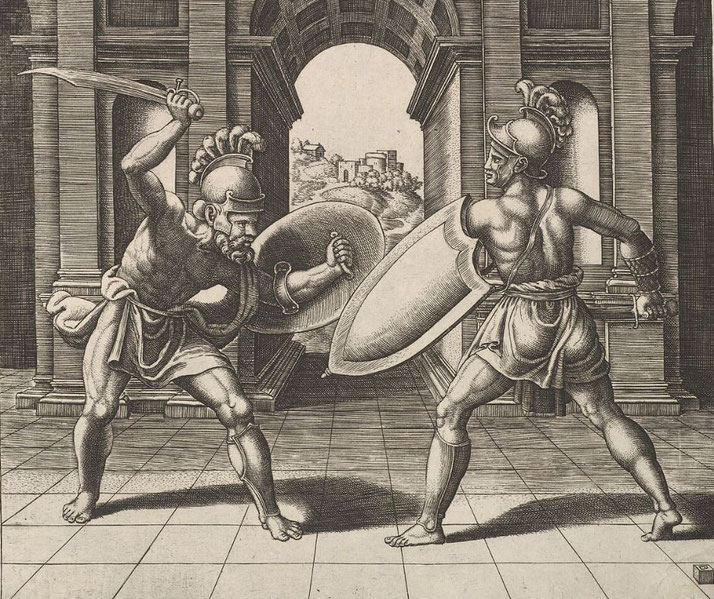

Here, in the world's most famous arena, gladiators – the ultimate warriors of the ancient world – prepare to engage in battles that are as much performances as they are bloody fights.

But who were the gladiators?

Who were the gladiators?

Gladiators are one of the most famous figures from ancient Rome and they existed between 207 BC and AD 404.

Gladiators were professional fighters that crowds of Romans could watch fight to the death in special arenas.

The name ‘gladiator’ is thought to have come from the Roman word for sword (gladius).

Due to their brutal fights, most gladiators lived very short lives, with most only living until their mid-twenties.

However, their fights became wildly popular and were one of the most-watched kinds of entertainment in ancient Rome.

The best gladiators were even treated like celebrities.

Most gladiators were slaves, ex-slaves, condemned prisoners, or enemies captured in war.

However, some people could volunteer to fight, as success in the arena promised fame and glory.

Surprisingly, one Roman emperor, Commodus, even took part in gladiator fights.

Training

Gladiators were owned by rich business owners (lanista in Latin), who were constantly looking for new fighters to become gladiators.

Young men were chosen to fight based upon their skill and strength.

Those who were chosen were trained in special ‘gladiator schools’, called ludi, to teach them the combat techniques required to survive in the area.

The ludi were often located close to the arena. The city of Rome had three gladiator schools next to the Colosseum.

The gladiator schools were similar to prisons: fighters usually lived in small cells and were often chained up when they weren’t training to keep them from escaping.

However, the trainees were also well cared for, since they cost their owners a lot of money to buy and train.

Therefore, gladiators were fed high-quality food to build their strength, and had experienced doctors to take care of any wounds or broken bones they received during training or fights.

Types of gladiators

There were different ways of fighting in the arena, and each gladiator was trained how to use a specific set of weapons and armour.

There were over twenty different kinds of gladiator, and each kind was called by a particular name, based upon their equipment or the region of the empire they came from.

Here are the most famous types that we know of:

Bestiarii

These were beast fighters. They were condemned to fight beasts and usually died in these battles.

Dimachaeri

This gladiator fought using two-swords, one in each hand.

Equites

These fighters fought on horseback with a spear and gladius. Most of the time, the equites only fought each other.

Essedarius

These were mounted gladiators, but very little is known about them, except that they fought mounted on chariots.

Hoplomachus

This is named after the Greek word for ‘fighter’ and based on classical Greek hoplites. They carried a spear, a short sword, and a small, round shield. They were often paired with murmillo or thraces for fights.

Murmillo

Known as the 'fish men' as their helmets (cassis crista) were decorated with pictures of fish (mormylos in Latin). They wore scale armour, used a short Greek sword and had an oblong Gallic shield. Murmillo was often paired with hoplomachus or thraces in fights.

Samnite

This type was the most heavily armed gladiator. They had large wooden shields (scutum), a helmet (galea), a short sword (gladius) and greaves. The samnites were the closest thing to a regular Roman legionary.

Retiarius

They were known as the 'net men' because they had weapons used by fishermen: a large fishing net (retes), a trident (fascina), a dagger, and a metal shoulder guard (galerus). They fought by attempting to trap their opponents with the net and stabbing at them with the trident. They were often paired against secutor or murmillo in fights.

Saggitarii

These gladiators were mounted on horses and used reflex bows.

Secutor

This gladiator had the same armour as a murmillo, including an oblong shield and a gladius sword. They were paired against retiarius.

Thraces

They had a small rectangular shield, a curved Thracian sword (sica), a helmet (galea) decorated with a griffin, and two thigh-length greaves. They were usually pitted against murmillo or hoplomachus.

Women

Almost all gladiators we know from ancient Rome were men. However, there were some female fighters, but they were often treated as a ‘strange’ form of entertainment rather than a regular type of gladiator.

Women were officially banned from taking part in gladiatorial contests around AD 200.

The fights

Typically, gladiators would only fight 2 or 3 times a year in stadiums where the ground was covered in a special sand called harena, which is where the name ‘arena’ comes from.

The most famous arena for gladiatorial combat was the Colosseum in Rome, which could hold over 50,000 spectators.

Most of the time, gladiators fought one another, but could also be forced to fight in chariots and even against wild animals.

Usually, gladiators fought in one-on-one combat rather than in large, multi-fighter combat.

As noted in the list above, certain types of gladiators were often paired with a particular type that had the opposite fighting styles.

This was probably to increase the entertainment value of the fight for the crowd.

Gladiatorial fights were organised occasions, much like modern sporting events. There were even official referees to ensure that rules were followed.

What happened if you won?

If a fighter was lucky enough to win a gladiatorial combat, they were given a range of possible rewards.

They could be given a branch of a palm tree as a trophy, or a ceremonial crown.

Other prizes known from history include silver dishes, prize money and on some rare occasions, if a fighter achieved a significant number of victories over many years, they could even be awarded their freedom.

Victorious gladiators, especially those who had a number of wins over time, became celebrities.

We have found a number of graffiti from ancient Roman buildings that show that people loved and supported their favourite fights, just like we follow our favourite sports teams today.

What happened if you lost?

Most people are surprised to learn that most fights did not end in the death of one of the combatants.

Since the owners of the gladiators had spent so much time and money training and feeding the fighters, they wanted them to survive as long as possible.

Instead, either the referee or the crowd would announce a winner and the fight would end.

We are told that often, a gladiator who had defeated his opponent, would ask the crowd for their opinion about what they should do.

The people watching could indicate with their hands whether the loser should live or die.

Based upon the crowd’s reaction, a referee, or the emperor himself, would then declare the outcome.

If a gladiator died at the end of a fight, their owner could fine the sponsor of the event to cover the cost of replacing the victim with a new slave.

It is estimated that around 8000 warriors died in the arena every year during the Roman period.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.