Sacred rituals and bloody ceremonies: Unmasking the true role of Aztec Priests

The history of the Aztecs, a civilization that dominated the heart of Mesoamerica in the 14th through 16th centuries, has always been a subject of intrigue and fascination.

Amidst tales of grandeur, conquests, and remarkable architectural marvels, the intricate and complex religious practices of the Aztecs stand out.

At the epicenter of this spiritual cosmos were the Aztec priests - the sacred intermediaries between the mortal world and the divine realms.

These men of faith held a position of remarkable importance, wielding considerable influence not only in spiritual matters but also in the societal, political, and even educational domains of the Aztec civilization.

Who were the Aztecs?

The Aztec civilization was a rich and vibrant culture that emerged as the dominant power in central Mexico from the 14th century until the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century.

Their capital, Tenochtitlan, constructed on an island in Lake Texcoco, was a marvel of urban planning and engineering with its intricate network of canals, magnificent temples, and bustling markets.

The city's grandeur amazed the Spanish upon their arrival, with many comparing it to the splendid cities of Europe.

The Aztecs were a stratified society with a distinct hierarchy, at the top of which sat the Huey Tlatoani, the Great Speaker, who ruled as the earthly embodiment of the Sun.

Beneath him were the nobility, which included military elites and high-ranking priests, who played vital roles in administrative, religious, and military affairs.

The lower strata consisted of commoners, merchants, artisans, farmers, and slaves.

Despite these hierarchies, the Aztec civilization was remarkably cohesive, bound together by shared cultural and religious values.

One of the distinguishing features of the Aztec civilization was its complex and multi-layered religious beliefs.

Their polytheistic religion was centered around a pantheon of gods who controlled different aspects of the universe, natural phenomena, and human life.

Huitzilopochtli, the sun and war god, Tezcatlipoca, the god of night, wind, and sorcery, and Tlaloc, the rain deity, were among the most revered gods.

The Aztecs believed in a cyclically created and destroyed world, and they saw themselves as living in the fifth and final era, a worldview that necessitated the continuous appeasement of the gods to maintain cosmic balance.

The central role of religious belief in Aztec society

Religion was not just a part of Aztec society—it was the very heart of it, permeating every aspect of daily life and shaping the civilization's world view.

Aztec religious beliefs were incredibly complex, incorporating aspects of mythology, ancestor worship, morality, and natural forces.

This polytheistic system was characterized by a multitude of gods, each governing over various elements of life and nature, thereby creating a cosmological model where humanity and divinity were intricately intertwined.

Religion was deeply interwoven into Aztec politics, governance, and social hierarchy.

The ruler, the Huey Tlatoani, was considered the representative of the sun god on Earth, solidifying the divine right to rule.

Every significant political decision or military campaign was intertwined with religious consultations, rituals, and divination, underscoring the significant role of religion in Aztec political life.

In the social sphere, religion played an equally prominent role. Major life events such as birth, marriage, and death were accompanied by significant religious rituals.

Aztecs observed a wide array of festivals and religious ceremonies throughout the year, each associated with specific deities and featuring its unique set of rites, sacrifices, dances, and songs.

These occasions served as communal events that strengthened social cohesion and emphasized shared cultural values.

Aztec religion was also an integral part of their education system. The children, whether they were from noble or commoner families, learned about religious traditions, rituals, and the pantheon of gods.

The moral code derived from their religious beliefs was taught as part of this education, guiding Aztecs in their conduct and ethics.

The different kinds of Aztec priests

The priests of the Aztec civilization held a unique and crucial position in society.

They were not just the intermediaries between the mortal world and the pantheon of gods, but also the bearers of religious knowledge, guardians of sacred rituals, interpreters of divine will, and essential players in the social, political, and cultural fabric of the Aztec society.

The priesthood was a highly organized and hierarchical institution in Aztec culture.

At the apex of this hierarchy was the High Priest, often referred to as the Quetzalcoatl Tlamacazqui.

This role was typically filled by a member of the nobility, reflecting the close ties between religious and political power.

Underneath the High Priest, there were a variety of other priestly roles, each associated with specific gods or temples, and each with their unique duties and rituals.

How to become an Aztec priest

Training to become an Aztec priest was a rigorous and demanding process, reflecting the immense responsibility these individuals would later bear.

The path to priesthood often began in childhood, with potential priests, usually from the nobility, enrolling in a special school called the Calmecac.

This institution was not just a school, but also a monastery, where the students led a disciplined and ascetic life and were taught by the older generation to take over their sacred duties.

The Calmecac curriculum was comprehensive and included subjects such as theology, ritual practices, divination, history, rhetoric, philosophy, the complex Aztec calendar, and the interpretation of religious texts and the pictographic writing system.

Students also learned music, poetry, and the art of public speaking – skills crucial for the performance of public religious ceremonies.

In addition to intellectual education, spiritual and moral training were also integral parts of a priest's formation.

Students were instructed in the principles of self-discipline, austerity, and self-sacrifice, often undergoing rigorous fasts and nocturnal vigils.

They were also taught the importance of penance, with self-bloodletting practices serving as a form of spiritual cleansing and a physical reminder of their dedication to the gods.

After years of rigorous education, when deemed ready by their mentors, the students would undergo the initiation process.

This involved several days of fasting, prayer, and ritual cleansing. The initiates were presented to the gods and took sacred vows to serve them.

The culmination of this process was a ceremony in which the newly initiated priests had their hair cut in a specific style that distinguished them as members of the priesthood.

Following this, they would be assigned their specific roles and responsibilities within the priestly hierarchy.

A day in the life of an Aztec priest

The daily life of an Aztec priest was a tapestry of rigorous duties, devotion, and community service.

These individuals, highly respected within the community, were central figures not only in religious affairs but also in the educational, moral, and sometimes even political aspects of society.

A priest's day would often start before sunrise. They would cleanse themselves in a ceremonial bath before attending to the sacred fires that had to be kept alight in the temples.

The priests would then offer prayers to the gods, often accompanied by the ritual of self-bloodletting as a personal sacrifice.

Throughout the day, priests would be involved in a variety of religious and societal activities.

They conducted public rituals and ceremonies, made astrological predictions, interpreted omens and signs, and performed the necessary rites for community events like births, marriages, and deaths.

One of their critical duties involved performing human sacrifices, which were considered essential to appease the gods and maintain balance in the universe.

Not only did they have to know the correct rites for the rituals, but the priests were also required to clean up the altar, temples, and implements after each sacrifice.

Priests also played a significant role in the education of young Aztecs. They taught at the Calmecac, where they imparted knowledge about religion, history, astrology, moral conduct, and other vital subjects.

This educational role also extended to the broader society as they provided moral and ethical guidance to the community, shaping the societal norms and values.

Even with their high status and important roles, Aztec priests led austere lives.

They followed strict rules, including celibacy for many, regular fasting, and self-inflicted bloodletting as acts of penance or devotion.

Their attire was simple, often consisting of a black or dark-colored robe, and their hair was typically worn long and matted, a symbol of their ascetic lifestyle.

While their lives were undoubtedly rigorous, the roles and duties of Aztec priests were seen as an essential service to the gods and their community.

They were the spiritual glue holding the society together, maintaining the celestial balance and ensuring the cultural continuity of the Aztec civilization.

Aztec priests and human sacrifice

One of the most infamous and misunderstood aspects of the Aztec civilization is the practice of human sacrifice.

This ritual, steeped in deep religious belief and symbolism, was primarily conducted by the Aztec priests, and it played a critical role in their cosmological understanding.

The Aztecs believed in a cyclic universe, one that had been created and destroyed four times before, and they were living in the fifth and final era.

This era's survival, according to their belief system, was dependent on the nourishment and appeasement of the gods, particularly the sun god Huitzilopochtli, who required the life-force or 'tonalli', associated with the heart, to battle the darkness and rise each morning.

Human sacrifices were seen as a form of repayment to the gods for the creation of humans and the sustenance of life and the universe.

The individuals sacrificed, often prisoners of war but sometimes volunteers or selected citizens, were considered 'ixiptla' or god impersonators.

The process of sacrifice was not seen as a death but rather as a direct union with the deity.

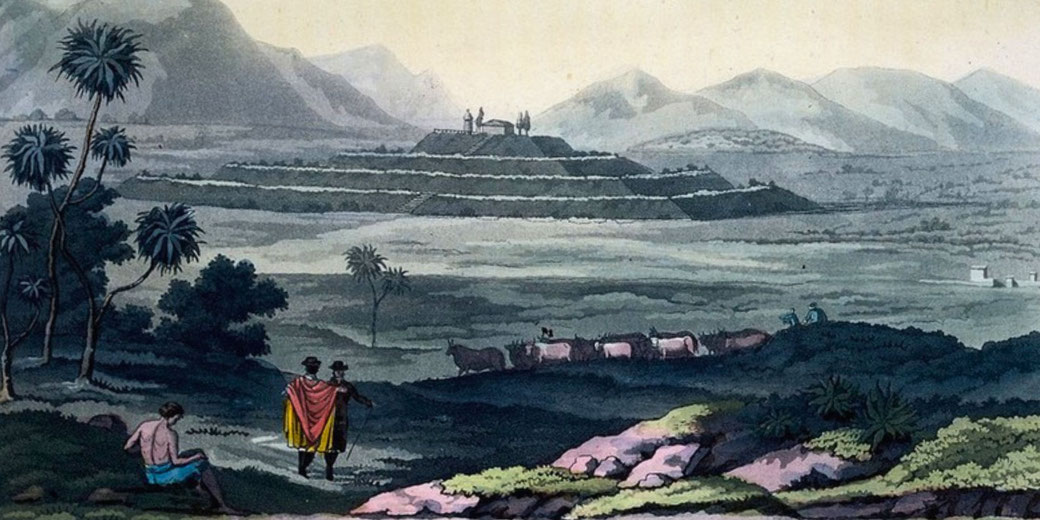

The ritual of human sacrifice was conducted with solemnity and reverence. It typically took place at the Templo Mayor, the main temple in Tenochtitlan, at the break of dawn.

The priests would lead the procession up the pyramid's steps, perform the sacrificial rituals, extract the heart, and offer it to the gods.

This was followed by the body's descent down the temple, symbolizing the journey of the sun across the sky.

It's important to recognize that, while it is the most notorious, human sacrifice was just one of many duties of the Aztec priests.

It was conducted within a broader system of rituals and ceremonies aimed at maintaining harmony between the human and divine realms.

Although unsettling by modern standards, it was a reflection of the Aztecs' profound sense of obligation to the gods and their cyclical understanding of life and death.

How the Aztec priests explained the universe

The Aztec cosmology was an intricate and multi-layered belief system that informed every aspect of their lives—from politics and warfare to agriculture and daily routines.

At the very core of this cosmological model were the Aztec priests, who served as the custodians and interpreters of this profound knowledge.

Aztecs believed in a universe that was divided into thirteen heavens (topan) and nine underworlds (mictlan).

These realms were populated by a myriad of gods and supernatural beings. The middle layer, where humans resided, was a floating island called Tlaltipac.

This cosmological view is often represented in the concept of the "Five Suns," referring to five epochs or "suns," each associated with one of the four cardinal directions and the center, and each ruled by a different deity.

Aztec priests were the ones responsible for interpreting and teaching this cosmological understanding to the rest of the society.

They were well versed in the intricate Aztec calendar systems—the 260-day sacred calendar (Tonalpohualli) and the 365-day solar calendar (Xiuhpohualli).

These calendars were not just measures of time but also crucial components of the Aztec cosmology. Each day was associated with a specific god and had a specific divine significance.

Priests also served as astronomers and astrologers, observing celestial bodies and interpreting their movements.

Planetary cycles, eclipses, and other celestial events were viewed as divine messages, and it was the duty of the priests to decipher these signs and their implications for the society.

The concept of 'Teotl', an animating life-force present in everything, was central to the Aztec cosmology.

It was the priests who performed rituals and ceremonies to harness and balance this energy, thereby ensuring the harmony between the cosmic forces and the earthly realm.

What happened to the priests when the Spanish arrived?

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early 16th century marked a tumultuous period for Aztec priests and the religious and cosmological system they upheld.

As the Spanish, led by Hernán Cortés, began to establish their rule, they embarked on a mission to convert the indigenous population to Christianity, which drastically affected the Aztec religious elite.

During the initial interactions between the Aztecs and Spaniards, the Aztec priests played a significant role.

They interpreted the arrival of the Spanish in the context of their prophecies, particularly the return of the feathered serpent god, Quetzalcoatl.

This interpretation influenced Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor, and his initial peaceful approach towards the foreigners.

However, as the Spanish became more aggressive and the reality of their intentions clearer, the role of the Aztec priests underwent significant changes.

They were among the most resistant to the Spanish, given their deep commitment to the Aztec gods and their central role in maintaining the traditional religious practices.

The Spanish, in their quest to Christianize the Aztecs, saw the Aztec religious system, particularly human sacrifice, as a primary target for elimination.

They destroyed Aztec temples and religious artifacts and disrupted religious ceremonies.

Many priests were killed or enslaved, while others were forced to convert to Christianity.

Despite this brutal suppression, some Aztec priests managed to continue their practices in secret, preserving their religious and cultural heritage.

They played a crucial role in recording and passing on the Aztec religious beliefs, rituals, and historical accounts, often blending them with Christian elements to survive the intense scrutiny of the Spanish authorities.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.