Silent killer of the Aztecs: The gruesome epidemic that toppled an empire

The Aztec Empire, once a beacon of power, sophistication, and cultural richness in the heart of Mesoamerica, met an abrupt and tragic end in the 16th century.

While the Spanish conquest led by Hernán Cortés is often credited for the empire's downfall, a silent and invisible enemy played an equally, if not more devastating, role in this historical narrative.

This enemy was disease, specifically smallpox, which swept through the Aztec population with a ferocity and speed that left an indelible mark on the course of history.

The Aztecs, like many indigenous societies of the Americas, had no natural immunity to many of the diseases brought by the Europeans.

Smallpox, a highly contagious and deadly disease, was one of these foreign invaders. It arrived in Mexico in 1520, just a year after Cortés, and it found a population that was completely vulnerable.

The disease spread rapidly, causing high mortality rates and contributing significantly to the social and political disruption of the Aztec Empire.

Background of the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, known more formally as the Triple Alliance, was a powerful political and military entity that dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 15th and early 16th centuries.

The empire was centered around the Valley of Mexico, with its capital, Tenochtitlan, located on an island in Lake Texcoco.

This city, with its grand temples, palaces, and bustling markets, was a testament to the Aztecs' architectural prowess and organizational skills.

The Aztec society was highly stratified, with a clear division of roles and responsibilities among its members.

At the top was the emperor, or 'tlatoani', who held absolute power. Below him were nobles, priests, warriors, merchants, artisans, farmers, and slaves.

This social hierarchy played a significant role in the functioning of the Aztec society, influencing everything from economic activities to religious practices.

The Aztecs were renowned for their advanced understanding of mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture.

They developed complex irrigation systems and were skilled in the art of terracing, enabling them to cultivate a variety of crops, including maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers.

Their calendar system, based on precise astronomical observations, was one of the most accurate of the ancient world.

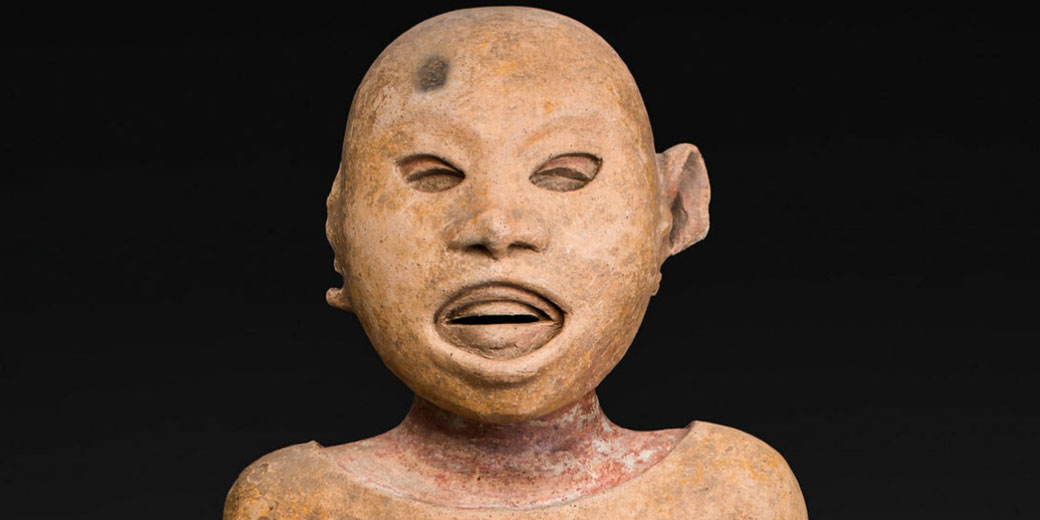

Religion was a central aspect of Aztec life, permeating every facet of their society. They worshipped a pantheon of gods, with rituals and ceremonies playing a significant role in appeasing these deities.

Human sacrifice, a practice often highlighted in descriptions of the Aztecs, was a part of these religious rites, believed to ensure the continued prosperity and survival of their civilization.

However, the Aztecs' understanding of health and medicine was rooted in their religious beliefs and cosmology.

They had a complex system of traditional medicine that involved the use of herbs, rituals, and the knowledge of healers, but they lacked an understanding of infectious diseases and how they spread.

This lack of knowledge, combined with the absence of natural immunity, would prove disastrous when they encountered the diseases brought by the Europeans.

Contact with Europeans

The first contact between the Aztecs and Europeans occurred in 1519, when a Spanish expedition led by Hernán Cortés landed on the eastern coast of Mexico.

Cortés, driven by tales of vast wealth and powerful empires in the interior of the continent, set out to explore and conquer these lands for the Spanish Crown.

The arrival of these strange men, with their steel weapons, horses, and unfamiliar customs, was met with a mixture of curiosity, awe, and fear by the Aztecs.

Cortés and his men made their way to Tenochtitlan, where they were initially received with hospitality by the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma II.

The Spanish were fascinated by the grandeur and complexity of the Aztec civilization, but they were also intent on converting the Aztecs to Christianity and gaining control over their wealth and resources.

This clash of interests and cultures set the stage for a series of conflicts and power struggles that would ultimately lead to the downfall of the Aztec Empire.

However, the Spanish brought with them more than just their religion, ambition, and weaponry.

They also brought diseases from the Old World, to which the indigenous populations of the Americas had never been exposed and against which they had no immunity.

One of these diseases was smallpox, which is believed to have been introduced to the Aztec population by an African slave who was part of the Spanish expedition.

The Outbreak

The smallpox outbreak in the Aztec Empire began in 1520, a year after the arrival of the Spanish.

The disease spread rapidly through the densely populated city of Tenochtitlan and the surrounding areas.

The death toll rose quickly in the first 60 days or so from the first infection, with some settlements losing as many as one third of their population.

Smallpox is transmitted from person to person, primarily through direct and fairly prolonged face-to-face contact.

In the crowded conditions of Tenochtitlan, with its large households and bustling markets, the virus found an ideal environment to spread.

The initial symptoms of smallpox include fever, headache, and body aches, followed by the appearance of a distinctive rash.

The rash develops into raised bumps filled with fluid, which eventually scab over and fall off.

The disease is particularly severe in individuals who have not been previously exposed or vaccinated, with a high mortality rate.

For the Aztecs, the disease was a terrifying and mysterious affliction. They had no knowledge of its cause, no effective treatments, and no way to stop its spread.

The disease struck indiscriminately, affecting people of all ages and social classes, including the emperor Cuitláhuac, who succumbed to the disease just a few months into his reign.

Impact on the Aztec Population

The impact of the smallpox epidemic on the Aztec population was catastrophic. It is estimated that between 1520 and 1521, the disease killed around a third of the population in the affected areas, including a significant proportion of the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan.

The actual numbers are difficult to determine due to the lack of accurate records, but it is clear that the death toll was in the hundreds of thousands, if not millions.

The disease did not discriminate between age, status, or occupation. From the highest nobility to the lowest classes, all were susceptible.

The loss of many leaders and experienced warriors severely weakened the Aztec's ability to resist the Spanish conquest.

Beyond the immediate death toll, the epidemic had profound social and psychological effects.

The sight of friends and family members succumbing to the horrific symptoms of the disease, coupled with the inability to understand or control its spread, must have been deeply traumatic.

The disease disrupted social structures, devastated families, and left many children orphaned.

The epidemic also had significant economic impacts. With a large portion of the population sick or dead, agricultural production would have been severely affected.

Food shortages and famine likely followed, exacerbating the suffering of the survivors.

How the Aztec Responded and Measures Taken

The Aztecs, like many pre-modern societies, had a complex system of traditional medicine that included the use of herbs, rituals, and the knowledge of healers known as 'ticitl'.

However, they had no understanding of infectious diseases and how they spread, and their medical practices were largely ineffective against smallpox.

When the epidemic struck, the Aztecs responded in the ways they knew. Healers would have used their knowledge of herbs and other natural remedies to treat the symptoms of the disease.

Rituals and prayers would have been performed to appease the gods and seek their intervention.

However, these measures were largely ineffective against the disease.

The Aztecs also attempted to isolate the sick, a common practice in many societies when faced with contagious diseases.

However, the crowded conditions in cities like Tenochtitlan, combined with the highly contagious nature of smallpox, made it difficult to control the spread of the disease.

The Spanish, for their part, were also largely helpless in the face of the epidemic.

While they had some knowledge of smallpox from their experiences in Europe, they had no effective treatments for the disease.

The concept of vaccination was not developed until the late 18th century, and the Spanish could do little more than watch as the disease ravaged the Aztec population.

Collapse of the Aztec Empire

The smallpox epidemic of 1520 was a major factor in the collapse of the Aztec Empire.

The disease struck at a time when the Aztecs were already under pressure from the Spanish conquest, and it significantly weakened their ability to resist.

The death of the Aztec ruler Cuitláhuac from smallpox just a few months into his reign was a major blow to the empire.

His successor, Cuauhtémoc, faced the daunting task of leading a population that was being decimated by disease and a city under siege by the Spanish and their indigenous allies.

The epidemic caused widespread death and suffering, disrupting social and economic structures and leaving the empire vulnerable.

With a significant portion of the population sick or dead, agricultural production would have been severely affected, leading to food shortages and famine.

The loss of many leaders and experienced warriors also weakened the Aztec's military capabilities.

In August 1521, after a prolonged siege, Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish.

Cuauhtémoc was captured and later executed, marking the end of the Aztec Empire.

The Spanish, led by Hernán Cortés, established the colony of New Spain, and the surviving Aztecs were subjugated and converted to Christianity.

Long-term Consequences

One of the most significant consequences was the demographic transformation of the region.

The smallpox epidemic, along with other diseases introduced by the Europeans, caused a dramatic decline in the indigenous population of the Americas.

In the case of the Aztecs, it is estimated that the population of the Valley of Mexico decreased by more than 60% in the century following the Spanish conquest.

This demographic collapse had profound social, economic, and cultural impacts, reshaping the region in ways that are still evident today.

The epidemic also facilitated the Spanish conquest and colonization of the region.

The fall of the Aztec Empire paved the way for the establishment of New Spain, a colony that would become one of the most important in the Spanish Empire.

The surviving Aztecs and other indigenous peoples were subjugated, converted to Christianity, and forced to adapt to Spanish rule.

Their lands, resources, and labor were exploited to support the colonial economy.

Culturally, the epidemic and the Spanish conquest led to a process of syncretism, with the blending of indigenous and Spanish traditions.

While many aspects of Aztec culture were suppressed or lost, others survived and adapted, influencing the development of Mexican culture.

The Nahuatl language, Aztec foods, and certain religious practices are among the elements of Aztec culture that have persisted.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.