What did Commodore Perry want from Japan?

Commodore Matthew Perry's mission to the Land of the Rising Sun marked a turning point not only in U.S.-Japan relations, but also in the broader context of international diplomacy and trade.

The story of Commodore Perry's expedition to Japan is one of ambition, determination, and the relentless pursuit of national interests.

It is a tale that unfolds against the backdrop of a rapidly changing world, where the forces of industrialization and imperialism were reshaping the global order.

Perry's mission was driven by a combination of economic, humanitarian, and strategic objectives, reflecting the multifaceted nature of American foreign policy in the mid-19th century.

America and Japan in the 19th century

The United States, having emerged from the Mexican-American War with vast new territories, was rapidly expanding both domestically and internationally.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 had triggered a massive westward migration, and the country was keen to establish secure and reliable sea routes to the West Coast.

Moreover, the U.S. was also eager to expand its trade relations, particularly in the resource-rich and largely untapped markets of the East Asia.

Across the Pacific, Japan was a nation in isolation. For over two centuries, under the policy of Sakoku, Japan had severely limited its interactions with the outside world.

Foreign trade was restricted to a small number of Dutch and Chinese merchants in the port of Nagasaki.

The shogunate, the military government of Japan, enforced this policy to maintain political stability and protect the country from foreign influences, particularly the spread of Christianity.

This isolation, however, also left Japan technologically behind the rapidly industrializing West.

Commodore Perry: The man and his mission

Matthew Calbraith Perry was born on April 10, 1794, in Newport, Rhode Island. He was the younger brother of Oliver Hazard Perry, a hero of the War of 1812.

Following in his brother's footsteps, Matthew Perry embarked on a naval career at an early age.

He served in the War of 1812, the Second Barbary War, and the Mexican-American War, earning a reputation as a skilled and disciplined naval officer.

His experience and leadership skills made him a natural choice for the challenging mission to Japan.

Perry was appointed by President Millard Fillmore to lead the U.S. Naval Expedition to Japan.

The primary objectives of the mission were twofold: to establish diplomatic relations and to negotiate a treaty that would ensure the safety of American sailors and open Japan to American trade.

The task was daunting, given Japan's longstanding policy of isolation and its resistance to foreign influence.

However, Perry was determined to succeed where others had failed.

In preparation for the expedition, Perry studied available information about Japan and its culture.

He understood the importance of demonstrating American technological superiority while also showing respect for Japanese customs and traditions.

He assembled a fleet of four ships, including two steam-powered frigates, the USS Mississippi and the USS Susquehanna.

The inclusion of these modern, powerful ships was a strategic decision, designed to impress the Japanese with American technological prowess—a tactic that would later be known as "gunboat diplomacy."

Perry's expedition set sail from Norfolk, Virginia, in November 1852. The journey was long and arduous, taking the fleet around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

The American arrival in Japan

Commodore Perry's expedition arrived in Edo Bay, present-day Tokyo Bay, on July 8, 1853.

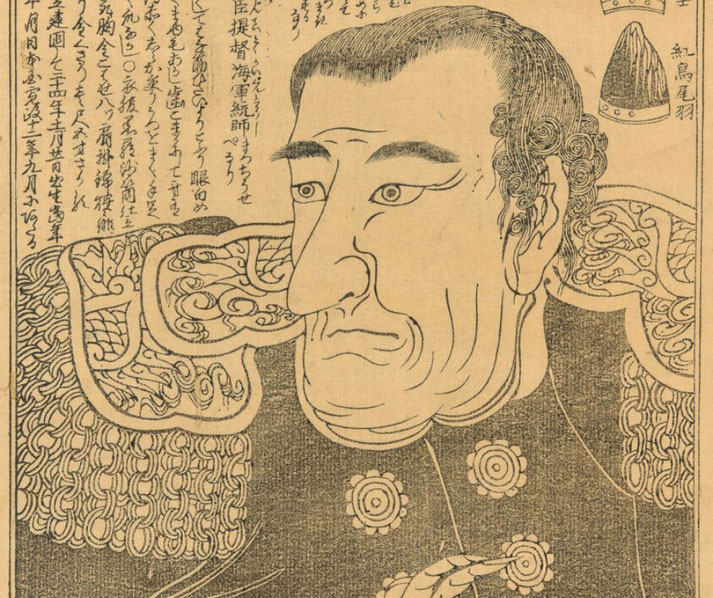

The sight of the American "Black Ships," as they were called due to the black smoke from their coal-fired steam engines, caused a sensation in Japan.

The Japanese had never seen such large, technologically advanced ships, and their arrival signaled a challenge to Japan's policy of isolation.

Perry refused to follow the usual protocol of dealing with local officials and insisted on delivering a letter from President Fillmore directly to representatives of the Japanese Emperor.

The letter outlined the objectives of the U.S.: the establishment of diplomatic relations, the opening of Japanese ports for American ships for supplies and repairs, and the fair treatment of shipwrecked American sailors.

Perry left the letter with the Japanese officials and departed, promising to return the following year for a response.

True to his word, Perry returned in February 1854 with a larger fleet. This time, he was prepared for lengthy negotiations.

The Japanese, recognizing the military power demonstrated by Perry's fleet and the potential threat it posed, decided to negotiate rather than risk a military conflict they knew they could not win.

After weeks of negotiations, the Treaty of Kanagawa was signed on March 31, 1854.

The treaty, the first between the U.S. and Japan, marked the end of Japan's 220-year-old policy of seclusion.

It provided for the return of shipwrecked American sailors, the opening of two ports to American ships for supplies and repairs, and the establishment of a U.S. consulate in Japan.

Did Perry achieve all of his objectives?

Commodore Perry's mission to Japan was driven by a combination of economic, humanitarian, and strategic objectives, reflecting the multifaceted nature of American foreign policy in the mid-19th century.

Firstly, the economic interests were paramount. The United States was in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, and its burgeoning industries were constantly seeking new markets for their goods. Japan, with its untapped markets, offered a tantalizing opportunity.

Moreover, American whaling ships operating in the Pacific needed Japanese ports for refueling and resupplying.

While the Treaty of Kanagawa did not immediately open Japan to American trade, it laid the groundwork for future trade agreements.

Secondly, there were humanitarian concerns. American sailors often found themselves shipwrecked on Japan's shores, and due to Japan's isolationist policies, they were often treated harshly.

The U.S. government sought to ensure the safety and fair treatment of these sailors.

The Treaty of Kanagawa addressed this issue by providing for the return of shipwrecked American sailors.

Lastly, the strategic interests of the United States played a significant role. The U.S. was keen to prevent any single foreign power from monopolizing access to Japan.

By opening Japan to American ships, the U.S. could ensure a balance of power in the region.

This was particularly important given the increasing influence of European powers in Asia.

The impact on Japan

In the immediate aftermath of the Treaty of Kanagawa, Japan's policy of isolation was effectively ended.

The treaty opened the door for other Western powers to negotiate similar agreements with Japan, leading to a period known as the "Unequal Treaties" due to the lopsided terms favoring the Western powers.

Japan was thrust onto the global stage, forced to interact with foreign powers and exposed to new ideas, technologies, and ways of governance.

The long-term consequences in Japan were even more significant. The inability of the shogunate to resist Western demands led to internal dissatisfaction and unrest, culminating in the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

This marked the end of the shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule. Under the Meiji Emperor, Japan embarked on a rapid process of modernization and westernization, transforming from a feudal society into a modern industrial state within a few decades.

The impact of Perry's expedition can still be felt today in Japan's status as a global economic and technological powerhouse.

For U.S.-Japan relations, Perry's expedition marked the beginning of a complex and evolving relationship.

From the initial contact marked by unequal treaties, the relationship has transformed over the centuries through war, alliance, and economic partnership.

Today, the U.S. and Japan are close allies, bound by shared democratic values and mutual security interests.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.