The significance of the Council of Trent in the history of the Catholic Church

In the middle of the 16th century, the Catholic Church was facing its biggest crisis in almost one and a half millennia. The rapid spread of Protestant challenges to its authority had seen a flood of people leaving the church, which triggered a widespread panic in its hierarchy.

After almost twenty years of confused delay, the pope finally decided to call a massive church council, which it hoped would finally heal this ruptured wound in the body of Christ.

But would it be too little, too late?

What were the causes of the Council of Trent?

On the simplest level, the rapid spread of Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation after 1517 was the primary cause for the calling one of the longest councils in ecclesiastical history.

By the 1530s and 1540s, Lutheran ideas had even won the support of many princes in Germany, which, from the church’s perspective, threatened the future unity of Christendom.

As a result, Pope Paul III recognized that the Church needed a new council to confront the new Protestant doctrines.

The complains that raised targeted the core Catholic teachings on salvation, sacraments, and their complex structures of authority.

All of these pressures also occurred at a time when the church was wrestling with ongoing internal Corruption.

For almost three hundred years, the Catholic Church had constantly tried to find ways to prevent a series of longstanding internal abuses, such as the sale of indulgences, clerical simony (buying church offices), pluralism (holding multiple benefices), and the lax morality of some clergy.

Each of those concerns had been blamed on the scandalization faithful churchgoers.

The failure to successfully address them had been among the causes of the Protestant revolt itself.

Church reformers had been calling for change, and even the Fifth Lateran Council in 1517 had proposed some reforms but with limited effect.

By the 1540s there was broad recognition that only a thorough council could address the moral and administrative failings of the Church.

However, the most public dispute that the council needed to address were theological in nature.

The Reformation movement had ignited fierce theological disputes that the Church needed to clarify.

The main issue included the source of Christian authority, whether it was scripture alone or scripture and tradition that was the source of doctrinal authority.

Also, there was the question about the doctrine of justification: did faith alone save someone, or was it a combination of faith and works?

But there were also questions around the nature and number of the sacraments, and the proper veneration of saints and relics.

Ultimately, Catholics and Protestants held fundamentally different positions on all of these points, which was leading to confusion and conflict, even among the protestants themselves.

A summary of what happened at the Council of Trent

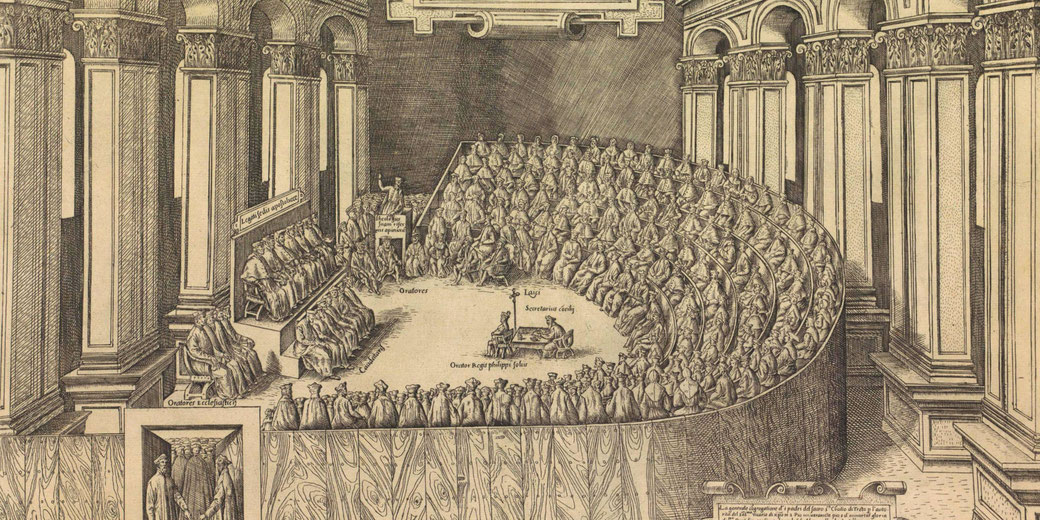

When it finally began in 1545, the Council of Trent was a truly monumental undertaking.

It wasn’t a single event but took place over 25 separate sessions over 18 years. To make it easier to understand, it is usually divided into three distinct phases:

First period took place under the pontificate of Pope Paul III. It opened on the 13th of December 1545, in Trent in northern Italy.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had been one of the strongest advocates for it, as he hoped it would heal the religious division in his empire.

In its early sessions, the council clearly reaffirmed traditional Catholic teachings such as the use of the Latin Vulgate Bible and the wording of the Nicene Creed.

It also began discussing reform of church discipline to finally address some of the abuses mentioned earlier.

However, in 1547, an outbreak of plague, along with some political tensions, prompted the council to temporarily transfer to Bologna, but by 1549, the council was suspended without finishing its work.

The second stage restarted the meeting after several years of delay. This time, Julius III was pope, and he officially reopened proceedings at Trent on 1 May 1551.

During this phase, the council issued important doctrinal decrees, including defining the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and reaffirming the sacrament of Penance.

To the surprise of many today, a number of Protestant representatives were invited and came to Trent under a safe-conduct to present their views. However, they were not given voting rights.

Once more, it was interrupted. In April 1552, an attack on the Emperor by a Protestant army under Elector Maurice of Saxony forced the council’s abrupt adjournment and no further sessions occurred under the following pope, Paul IV.

It would be ten years later before the third phase was finally called by Pope Pius IV after Paul IV’s death.

This time it reassembled in Trent in January 1562, with a much larger attendance of bishops.

It also included, finally, a delegation of French prelates who had boycotted the two earlier sessions.

Over nearly two years, the council completed its sweeping agenda and issued decrees on topics ranging from the Mass and holy orders to marriage, saints, and indulgences.

Then, on the 4th of December 1563, the Council of Trent held its 25th and last session.

It concluded with solemn praises for the Pope and secular rulers who supported the council.

The final decrees were then sent to Rome for papal ratification. Notably, none of the reigning Popes (Paul III, Julius III, or Pius IV) ever attended the Council of Trent in person; instead, papal legates were sent to preside over the proceedings.

How the Council of Trent changed the Catholic Church

On the surface, the documents produced by the council appeared to change little in regard to Catholic doctrine.

For example, it made an effort to clarify and codify long-standing Catholic beliefs.

However, its canons and decrees set in stone for the first time the Catholic response to Protestant theology, often ending with an ‘anathema’, which was an excommunication, for anyone holding the condemned views.

As such, it provided a clear identity for the Catholic Church for the next four centuries.

Perhaps the most significant change was the fact that Trent launched a vigorous Catholic revival by prompting major reforms in the church.

Some of the key reforms included establishing seminaries in every diocese in order to properly train priests.

This was meant to raise the intellectual caliber of the clergy. The council also required bishops to officially remain in their dioceses so as to end the practice of absentee bishops holding multiple positions.

Luxurious lifestyles among church leaders were condemned, while the giving of church offices to relatives, known as nepotism, was forbidden.

On a practical level, Trent addressed the pastoral care of the faithful, in that it instructed priests and bishops to preach regularly, to teach the catechism, and provide the sacraments to the people on a consistent and regular basis.

In the years immediately after 1563, the papacy carried out the council’s directives by issuing a new Roman Catechism in1566 to help teach the faith effectively, while revising the Roman Breviary in 1568, and the Missal in 1570.

Ultimately, this led to the development of the ‘Tridentine Mass’: a uniform Latin Mass that remained the norm in the Catholic Church for 400 years.

Remarkably, this Tridentine consolidation of liturgy and doctrine resulted in a stability in the Catholic form of worship right up until the 20th century.

Why the Protestants were still angered

While the Council of Trent generally revitalized Catholicism, it failed to heal the split in Western Christianity.

Trent’s decrees took a hard line and made no compromises with Protestant theology.

As a result, the Catholic-Protestant divide became permanent. After Trent, Europe entered an era of entrenched confessional divisions: Catholic regions and Protestant regions solidified their separate identities, often backed by different state powers.

The council’s firm stance arguably cemented the schism that had begun with the Reformation.

In the following decades, this polarization played out in conflicts like the French Wars of Religion and eventually the Thirty Years’ War.

There were a number of a decisions that the Protestants could not accept. For example, Trent rejected the Protestant doctrine of ‘justification by faith alone’.

Instead, it insisted that faith must be accompanied by love and good works aided by God’s grace.

In its Decree on Justification (1547), the council taught that humans cooperate with divine grace in the process of salvation, as opposed to the Lutheran view of passive, imputed righteousness.

The council declared that grace is not a one-time guarantee; it can be forfeited by mortal sin, and Christians must persevere in faith and penance.

Anyone claiming assurance of salvation by faith alone was anathematized.

What is more, Trent reaffirmed the Eucharist, the bread and wine, are truly transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ: a doctrine it described using the term ‘transubstantiation’.

Also, the Eucharist was officially defined as a propitiatory sacrifice offered to God for the living and the dead.

As a result, the Mass was explicitly affirmed as a true sacrifice. This was a direct challenge to Protestant claims that it was only a memorial meal.

Did the Council of Trent add books to the Bible?

During its Fourth Session on April 8, 1546, the Council of Trent issued a decree that officially confirmed the canon of Scripture, which included the 46 books of the Old Testament and 27 books of the New Testament.

At the time, it was the same canon as had been used in the Latin Vulgate Bible. This reaffirmation was considered necessary as part of the council because Protestant reformers, such as Martin Luther, had openly rejected several Old Testament books.

Luther did this based upon the Jewish Masoretic Text of the Old Testament, which did not include several books that had been part of Christian Bibles since the early Church.

The books that Protestant reformers removed were Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch (including the Letter of Jeremiah), 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, as well as additional passages in Daniel and Esther, which were found in the Septuagint.

However, the Church declared that each of these books had been widely used in the early Church and, since they were included in the Septuagint, which was the version of Scripture most commonly used by early Christians, they should be reaffirmed as part of the traditional canon that had been used in the Church since at least the 4th century.

The notorious ‘Index of Forbidden Books’

One of the most uncomfortable outcomes of the council was a decision that was made to help combat heresy through the spread of dangerous or ‘unorthodox’ writings.

Trent called for the creation of an Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1562, during the 18th session.

It appointed a commission to compile this list, but the task of finalizing the list was left to the pope himself.

Shortly after the council, in 1564, Pope Pius IV published the first Tridentine Index.

This specifically catalogued works by Protestant reformers and other writings forbidden to Catholics.

The Index remained in force for centuries as a tool to prevent the laity and clergy from reading materials contrary to the Catholic faith.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.