Cuzco's grandeur: The incredible history of the capital city of the Inca Empire

Every civilization has a heart, a pulsating center that feeds life into its societal body, fueling culture, politics, economy, and spirituality.

For the Inca Empire, a civilization that once spread across much of western South America, that beating heart was Cuzco. Nestled in the southeastern part of what is now modern-day Peru, Cuzco was more than just a city.

It was a symbol of Inca supremacy, a testament to their architectural prowess, and a vessel carrying the lifeblood of their rich culture and traditions.

Cuzco, often referred to as the 'navel of the world' by the Incas, was the epicenter of the Inca civilization. As the capital of the largest pre-Columbian empire in the Americas, its story is one of resilience, adaptation, and transformation.

It was here that the Incas built their most sacred temples, their grandest palaces, and administered a vast empire that stretched from Colombia to Chile.

The geographical brilliance of the city's founding

Situated high in the Andes Mountains in the southeastern region of modern-day Peru, Cuzco’s strategic location played a pivotal role in its development and rise as the capital of the Inca Empire.

At an elevation of around 11,152 feet, the city was literally and metaphorically at the zenith of the Inca world.

Surrounded by lush valleys and bisected by the Saphi River, Cuzco offered a fertile and defensible location that was befitting of an imperial capital.

Geographically, the Cuzco valley is part of the larger region known as the Sacred Valley of the Incas.

This area was a key section of the Inca Empire, the Tawantinsuyu, which spanned across a vast swath of the South American continent, covering parts of modern-day Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

The high altitude and rugged terrain provided natural barriers against invasions, enabling the Incas to develop and consolidate their power in relative peace.

Cuzco's location in the mountainous terrain of the Andes led the Incas to develop sophisticated agricultural techniques, like terracing, which maximized the use of arable land and helped sustain the city's population.

The presence of the Saphi River, along with several streams feeding into it, facilitated the construction of complex irrigation systems, thereby bolstering the agricultural capabilities of the region.

Interestingly, the Incas incorporated their profound respect for the natural world into the city's layout.

Cuzco was designed to mimic the shape of a puma, a sacred animal in Inca cosmology.

The Sacsayhuamán fortress represented the head of the puma, while the Tullumayo River delineated its spine.

This unique incorporation of geography into urban planning reflected the Incas' intimate relationship with nature and their keen understanding of their environment.

The history of Cuzco before the Inca arrived

While the Incas may be the civilization most famously associated with Cuzco, the city's history extends far beyond their reign.

Its origins date back to nearly a millennium before the rise of the Inca Empire.

Evidence from archaeological excavations reveals that the Cuzco valley was inhabited by pre-Inca cultures, with the earliest human settlements tracing back to around 2000 BCE.

The people who first settled in the Cuzco region were primarily farmers and herders.

They cultivated potatoes and maize and raised llamas and alpacas for sustenance.

These early inhabitants also developed rudimentary pottery and weaving skills, setting the foundation for the intricate textile designs that would later characterize Inca culture.

From the 7th to 9th centuries, the city was under the control of the Wari Empire, a civilization that dominated the Peruvian highlands and coasts.

The Wari introduced more advanced agricultural techniques, such as terracing and irrigation, which allowed for more efficient use of the high-altitude environment.

They also constructed roads and other infrastructure that would later be expanded by the Incas.

In the centuries that followed the collapse of the Wari Empire, Cuzco was inhabited by a number of smaller ethnic groups.

These groups, collectively known as the Killke, held control over the region from 900 to 1200 CE.

They were responsible for constructing the original version of the Sacsayhuamán fortress, which the Incas would later expand into an impressive citadel.

While these early cultures did not achieve the grandeur of the later Inca Empire, they nevertheless laid much of the groundwork upon which the Incas would build.

The agricultural practices, infrastructure, and artistic techniques of the pre-Inca cultures greatly influenced the development of the Inca civilization.

The dramatic arrival of the first Inca

The Incas trace their origins to a legendary tale of the first Inca, Manco Cápac, and his sister-wife, Mama Ocllo.

According to mythology, they emerged from the sacred Lake Titicaca, sent by the Sun God, Inti, to bring civilization to the people and to find the navel of the world, where they were to build a great city.

This quest led them to the future site of Cuzco, where Manco Cápac plunged his golden staff into the ground, signaling that they had found the promised location.

Historically, the Incas began as a small tribal group in the Cuzco region around the early 13th century.

Their transformation into an empire, however, didn't occur until the reign of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui in the mid-15th century.

Often compared to Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar in terms of his impact, Pachacuti is widely considered the architect of the Inca Empire, or Tawantinsuyu, which means "the four parts together," referencing the four corners of the empire.

Under Pachacuti's rule, Cuzco evolved from a minor regional center into the capital of a rapidly expanding empire.

He embarked on a series of military campaigns that brought large portions of the Andean region under Inca control.

His visions also led to significant urban and architectural projects, transforming Cuzco into an impressive city of stone.

Key to the Inca's rapid expansion was the policy of incorporating the gods, customs, and traditions of conquered peoples into their own religious and societal structure.

This inclusive approach fostered unity and loyalty, mitigating resistance and helping to hold the sprawling empire together.

The Inca Empire continued to grow after Pachacuti's reign, reaching its peak in the early 16th century.

By this time, it stretched from present-day Colombia in the north to Chile in the south, making it the largest empire in pre-Columbian America.

Through this growth and consolidation, Cuzco remained the political, administrative, and religious hub, maintaining its position as the sacred city of the Inca Empire.

Spectacular architecture and urban planning of Cuzco

Cuzco, during the zenith of the Inca Empire, was carefully designed and constructed, reflecting both the Incas' respect for their natural environment and their advanced understanding of urban planning.

The Incas viewed their capital as a reflection of the cosmos. This intimate connection between urban planning and the natural world was a hallmark of Inca architecture.

The city's design was orderly and symmetrical, with clearly delineated areas for administrative, religious, and residential structures.

Roads and plazas were carefully arranged, demonstrating the Incas' profound understanding of city planning.

Two primary roads, the Collasuyo route to the highlands and the Antisuyo route to the jungle, converged at the main square, the Huacaypata.

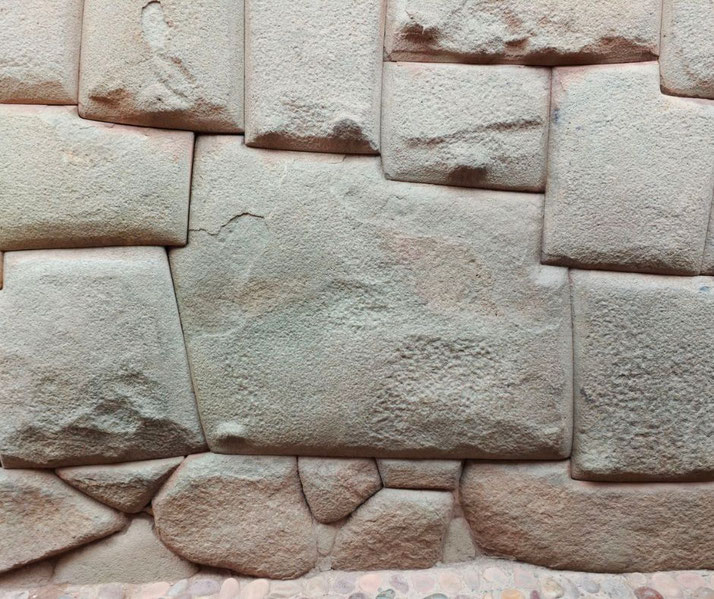

Inca architecture is renowned for its stonework. Masons would meticulously chisel stones so they fit together without mortar, a method known as ashlar.

The precision of their work was so accurate that even after centuries and numerous earthquakes, many of the structures remain standing, and a knife blade cannot fit between the stones.

The twelve-angled stone found in a wall of the Hatun Rumiyoc street is a renowned example of this technique.

Notable structures within Cuzco included the Qorikancha (the Temple of the Sun), the most important temple in the Inca Empire, originally lined with gold sheets, and Sacsayhuamán, a colossal fortress made of massive stones.

Residential districts, known as canchas, comprised walled compounds containing multi-family residences organized around central courtyards.

The Inca's architectural genius wasn't only in the design and construction of individual buildings.

It extended to their understanding of the city as a complex, interconnected entity.

They developed a comprehensive system of roads, bridges, and pathways, integrating Cuzco with the rest of the empire.

The ceque system, a series of ritual lines radiating from the Qorikancha, defined sacred spaces, shrines, and agricultural lands, illustrating how the city was an integral part of a larger sacred geography.

The fall of Cuzco to the Spanish

The Spanish arrival in the 16th century marked a devastating and transformative chapter in the history of the Inca Empire and its capital, Cuzco.

This period was characterized by violent conflict, political upheaval, and the rapid decline of Inca power in the face of European colonialism.

In 1532, Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his small force of men landed on the shores of the Inca Empire.

The timing of their arrival was opportune. The empire was still recovering from a brutal civil war between the sons of the late Sapa Inca, Huayna Capac - Atahualpa and Huáscar - and was further weakened by an outbreak of smallpox, introduced by the Europeans, which had killed a significant portion of the population, including Huayna Capac himself.

In an infamous event known as the capture of Atahualpa, the Spanish, despite being vastly outnumbered, seized the Sapa Inca during a meeting in Cajamarca.

They demanded and received a vast ransom for his release, only to execute him in 1533, leaving the empire leaderless.

In 1533, the Spanish entered and captured Cuzco with relatively little resistance. They installed a puppet Sapa Inca, Manco Inca Yupanqui, to help control the Inca population.

However, in 1536, Manco Inca led a rebellion against the Spanish, resulting in a destructive conflict known as the Siege of Cuzco.

Although the Incas were initially successful, they were ultimately unable to dislodge the Spanish, who had superior weaponry and received reinforcements.

Despite the fall of Cuzco, Inca resistance continued in the form of the Neo-Inca State, centered in Vilcabamba.

This holdout state lasted until 1572 when the last Inca ruler, Túpac Amaru, was captured and executed by the Spanish, effectively ending the last vestige of the Inca Empire.

What happened to Cuzco after the conquest?

Following the Spanish conquest, Cuzco underwent dramatic transformations as it was reshaped according to Spanish colonial norms, yet the city also retained and adapted many aspects of its Inca past, resulting in a unique blend of cultures that persists today.

Cuzco became a significant colonial center in the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru. The Spanish settlers implemented a series of architectural, political, and societal changes.

They built upon the existing Inca city, reusing many structures but also introducing their own architectural styles.

Spanish Baroque churches and mansions rose alongside Inca walls and foundations, creating a distinctive fusion of architectural styles that characterizes Cuzco's cityscape to this day.

The Spanish also imposed their own administrative systems, replacing the Inca's complex bureaucracy with their own colonial governance structure.

Spanish became the dominant language, Catholicism replaced the Inca polytheistic religion, and European customs were introduced.

However, the transition was not entirely one-sided. The Incas, and their Andean descendants, adapted to these changes while also retaining significant aspects of their own culture.

Indigenous languages like Quechua continued to be spoken, and many Inca customs, beliefs, and practices survived, often syncretizing with Spanish elements.

Inca agricultural practices, for instance, were maintained and adapted, helping the city to continue prospering.

Cuzco also continued to be a place of symbolic importance for the Andean people. Despite the Spanish attempts to suppress Inca culture, the memory of the Inca Empire remained powerful.

Many indigenous rebellions against Spanish rule were centered in or around Cuzco, such as the rebellion led by Túpac Amaru II in 1780, which was one of the largest indigenous uprisings in the colonial period.

In the centuries following the conquest, Cuzco has continued to evolve. It has navigated the path to independence, industrialization, and modernization, all while dealing with the legacies of both its Inca past and its colonial history.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.