What was life like in Edo Period Japan?

The Edo Period, also known as the Tokugawa Period, was a significant era in Japanese history that lasted from 1603 to 1868.

This period was characterized by relative peace, stability, and isolation, marking a stark contrast to the preceding age of civil war and unrest.

The Edo Period was named after the city of Edo, now known as Tokyo, which became the political center of Japan under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Despite its isolationist policies, the Edo Period was a time of significant cultural and societal growth in Japan. The stability provided by the shogunate's rule allowed for the flourishing of various forms of art, literature, and theater.

The period also saw the rise of a vibrant urban culture in cities like Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto, where the merchant class thrived.

Who held the power in the Edo Period?

The political structure of Edo Period Japan was characterized by a feudal system under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate.

This period marked the last era of traditional Japanese government and the final stage of the social and political system established by the samurai class.

At the apex of this structure was the shogun, the military dictator of Japan. The shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who, after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, was appointed shogun by the emperor in 1603.

The emperor, while revered as a divine figure, held little political power and was largely a symbolic figurehead.

The real power lay in the hands of the shogun, who ruled from Edo, the political and cultural hub of Japan.

The shogunate implemented a centralized feudal system, where power was distributed among regional lords known as daimyos.

These daimyos were divided into several categories based on their relationship and loyalty to the Tokugawa.

The most loyal were the "fudai" daimyos, who were often given important government posts.

The "tozama" daimyos, who were less trusted, were kept at a distance from the central power.

The daimyos ruled their respective domains semi-autonomously but were subject to the shogunate's laws and regulations.

They were required to spend every other year in Edo, a policy known as "sankin-kotai."

This system was a strategic move by the shogunate to control the daimyos by keeping their families as virtual hostages in Edo during their absence.

Beneath the daimyos were the samurai, the warrior class. They served as the military and administrative apparatus of both the shogunate and the daimyos.

Despite their high social status, many samurai lived modestly and were often in financial distress due to the largely non-monetary stipend system.

What social class would you have been in?

The social structure was strictly hierarchical, with four main classes: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants.

This system, known as the "Shi-no-ko-sho" system, was based on Confucian ideals, which valued agriculture and discouraged commerce.

The samurai were at the top of the hierarchy, followed by farmers, artisans, and merchants.

However, the reality was more complex, with the merchant class, despite being at the bottom of the hierarchy, growing increasingly wealthy and influential due to the era's economic prosperity.

Women's roles in Edo society were also defined by strict Confucian values.

Women were expected to be obedient wives and mothers, and their lives were largely confined to the domestic sphere.

However, some women managed to exert influence in the arts, literature, and even business.

Fashion during the Edo Period was diverse and vibrant, reflecting the era's cultural dynamism.

The kimono was the standard attire for both men and women, with styles and patterns varying based on class, age, and occasion.

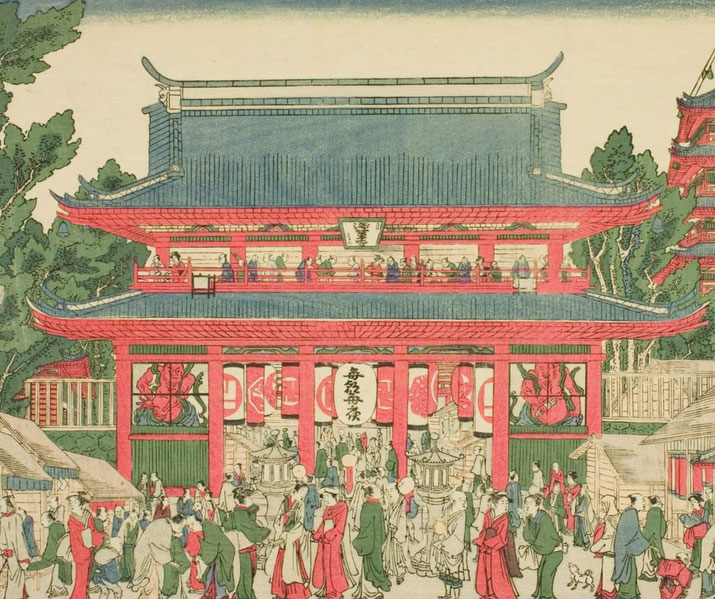

The period also saw the development of "ukiyo-e," a genre of woodblock prints that depicted scenes from everyday life, landscapes, and even kabuki actors.

Food culture also flourished during the Edo Period. Sushi, tempura, and soba became popular, and the tea ceremony, which embodied the spirit of "wabi-sabi" (the appreciation of simplicity and transience), was widely practiced.

Going to school

The Edo Period was a time of significant advancement in education and learning in Japan.

Despite the rigid social hierarchy, there was a widespread belief in the value of education, leading to the development of various educational institutions and a high literacy rate compared to other parts of the world during the same period.

The most common form of education for commoners was provided by "terakoya," or temple schools.

These schools were often run by Buddhist temples or private educators and offered basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

The curriculum was practical, focusing on skills necessary for daily life and work. By the end of the Edo Period, it is estimated that over half of the male population and a significant portion of the female population had some form of schooling, a testament to the widespread accessibility of education.

For the samurai class, education was more formal and rigorous. Samurai were expected to be not only skilled warriors but also learned men.

They were educated in a variety of subjects, including military strategy, martial arts, literature, and philosophy.

Confucian classics were a significant part of the curriculum, emphasizing moral virtues such as loyalty and filial piety.

Many samurai also pursued arts such as calligraphy, tea ceremony, and poetry, embodying the ideal of the "bunbu-ryodo," or the pen and the sword in accord

The Edo Period also saw the establishment of "hanko," or domain schools, by daimyos.

These schools were intended to educate the children of samurai in the domains, focusing on both martial and academic subjects.

Some of these schools even allowed commoners to attend, reflecting the changing social attitudes towards education.

The era also witnessed the rise of "rangaku," or Dutch studies. With Japan's isolationist policy, the Dutch were one of the few windows to the Western world, and scholars studied Dutch texts to learn about Western science, medicine, and technology.

What was it like to live in the city of Edo?

The Edo Period witnessed the rise of bustling urban centers, with Edo (modern-day Tokyo) emerging as one of the largest cities in the world.

Urban life during this time was vibrant and dynamic, characterized by a flourishing economy, a thriving cultural scene, and a sophisticated infrastructure system.

Edo, the seat of the Tokugawa shogunate, was the epicenter of political power and cultural activity.

The city was meticulously planned, with the shogun's castle at the center, surrounded by the residences of the daimyos.

Further out were the districts of the samurai, merchants, and artisans. The city was crisscrossed by canals and bridges, and punctuated by fire towers, as fires were a constant threat in the densely populated city.

Life in Edo was vibrant and diverse. The city was home to a thriving merchant class, who ran businesses ranging from small shops to large trading houses.

The city's streets were lined with a variety of establishments, including teahouses, restaurants, bathhouses, and theaters.

Edo was also the center of the "ukiyo" or "floating world" culture, characterized by pleasure-seeking activities such as kabuki theater, courtesan quarters, and sumo wrestling.

Infrastructure and city planning were advanced for the time. The shogunate implemented strict building codes and city planning rules to prevent fires and maintain order.

The city was divided into distinct districts for different classes, and large boulevards were designed for easy troop movement.

Edo also had an extensive water supply system, with aqueducts and canals providing clean water to the city's residents.

Public services were also well-developed. The city had a professional firefighting force, and the shogunate maintained public order through a network of local officials and neighborhood associations.

There were also various social welfare programs, including public granaries to provide for the poor during famines.

What was daily life like in the Edo Period?

Daily life during the Edo Period varied greatly depending on social status, occupation, and whether one lived in a rural or urban area.

However, despite these differences, there were common threads that ran through the fabric of everyday life in Edo Japan.

For the samurai class, daily life was a balance between their duties as warriors and administrators and their cultural pursuits.

Samurai were expected to be skilled in martial arts, but they also engaged in scholarly activities such as reading, writing, and studying Confucian classics.

They also practiced arts like tea ceremony, calligraphy, and poetry. The samurai lived by a strict code of conduct known as "bushido," which emphasized virtues such as loyalty, honor, and self-discipline.

Farmers, who made up the majority of the population, led a life centered around agriculture.

Their daily routine was dictated by the seasons and the demands of their crops. Despite their hard work, farmers were often at the mercy of weather conditions and the heavy taxes imposed by the shogunate and daimyos.

Artisans and merchants, who lived primarily in urban areas, had a different rhythm of life.

Artisans, such as blacksmiths, carpenters, and weavers, spent their days crafting their goods.

Merchants ran a variety of businesses, from small shops to large trading houses. Despite being at the bottom of the social hierarchy, many merchants were prosperous and lived comfortable lives.

Daily life in urban areas like Edo was vibrant and diverse. The streets were bustling with activity, from the busy markets to the lively entertainment districts.

People enjoyed various forms of entertainment, such as watching kabuki theater, visiting pleasure quarters, or simply strolling along the river and enjoying the cherry blossoms.

Food was an important part of daily life, and the Edo Period saw the development of many dishes that are still popular today, such as sushi, tempura, and soba noodles.

Tea was also a popular beverage, and the tea ceremony was a cherished tradition.

Why the Edo Period came to an end

The end of the Edo Period, also known as the Bakumatsu, was a time of significant upheaval and change in Japan.

The period was marked by internal strife, external pressure from foreign powers, and a growing discontent with the Tokugawa shogunate's rule.

The seeds of discontent were sown by a variety of factors. The strict social hierarchy and the shogunate's authoritarian rule led to resentment among the lower classes and the samurai, who were facing financial difficulties due to the changing economy.

The shogunate's policies, particularly its isolationist stance, were increasingly seen as outdated and unable to meet the challenges of the modern world.

The arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and his "Black Ships" in 1853 was a watershed moment.

Perry's demand that Japan open its ports to trade with the United States was a stark reminder of the country's vulnerability to foreign powers.

The shogunate's decision to sign unequal treaties with Western powers, granting them extraterritorial rights and imposing low tariffs, was met with widespread opposition and further undermined the shogunate's authority.

These tensions culminated in a series of rebellions and civil wars, most notably the Boshin War of 1868-1869.

The conflict pitted forces loyal to the shogunate against those seeking to restore the emperor's power.

The imperial forces, backed by powerful domains like Satsuma and Choshu and advocating for the slogan "sonno joi" (revere the emperor, expel the barbarians), emerged victorious.

The defeat of the Tokugawa shogunate marked the end of the Edo Period and the beginning of the Meiji Era.

The Meiji Restoration, as it came to be known, ushered in a period of rapid modernization and westernization.

The emperor was restored to power, and the feudal system was abolished. Japan embarked on a path of modernization, seeking to learn from the West while maintaining its unique culture and identity.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.