How did Christianity change from a persecuted minority to the largest religion in the world?

Christianity, the world's largest religion with over two billion followers, has a history that is as fascinating as it is complex.

Its journey from a small, persecuted sect in the Roman Empire to a global faith that spans continents and cultures is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of its teachings and followers.

In the first century CE, Christianity emerged in the eastern Mediterranean region, born out of Jewish traditions and centered around the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

It was a time of great upheaval, with the Roman Empire exerting its influence over vast territories. Christians, seen as subversive and threatening to the established order, were often persecuted and forced to practice their faith in secret.

Yet, despite these challenges, Christianity not only survived but thrived, evolving from a persecuted minority into the state religion of the Roman Empire within a few centuries.

How Christianity began

The origins of Christianity can be traced back to the 1st century CE in the eastern Mediterranean region, specifically in Judea, a province of the Roman Empire.

This was a time of significant political and social change, with various cultures and religions intersecting under Roman rule.

It was within this context that Jesus of Nazareth, the central figure of Christianity, emerged.

Jesus, a Jewish preacher and healer, began his ministry around the age of 30. His teachings, which emphasized love, forgiveness, and the coming of the Kingdom of God, attracted a following.

His message was revolutionary, challenging both the religious and social norms of the time.

Jesus' followers, who believed him to be the Messiah—the Savior promised in Jewish scriptures—began to spread his teachings.

However, his message was seen as a threat by both the Jewish religious authorities and the Roman government.

In approximately 30-33 CE, Jesus was sentenced to death by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate. He was ordered to be crucified, an execution method reserved primarily for criminals and political dissidents.

His death, however, was not the end of his movement. His followers claimed that he had risen from the dead three days after his crucifixion, an event known as the Resurrection.

This became the central tenet of the Christian faith, symbolizing hope and eternal life.

The followers of Jesus, initially a small group of disciples, began to spread his teachings more widely, forming the early Christian Church.

The early Christians, or 'followers of the Way' as they were initially known, were predominantly Jewish and continued to participate in Jewish religious life.

However, tensions soon arose due to their belief in Jesus as the Messiah and their inclusion of Gentiles (non-Jews) without requiring adherence to traditional Jewish laws.

This led to increasing separations between Judaism and the nascent Christian movement.

Despite being a minority and facing persecution, early Christians were resilient. They established communities, developed rituals, and began to formulate doctrines.

The writings of the apostles and early Church leaders, which later formed the New Testament of the Christian Bible, played a crucial role in defining Christian beliefs and spreading the faith.

How it gained followers in the Roman Empire

One of the key figures in the early spread of Christianity was Paul the Apostle. Originally a persecutor of Christians, Paul converted after experiencing a vision of the resurrected Jesus on the road to Damascus.

He became a tireless missionary, traveling extensively throughout the Roman Empire and establishing Christian communities in key cities such as Corinth, Ephesus, and Philippi.

Paul's letters to these communities, many of which are included in the New Testament, provided guidance on Christian doctrine and practice, and played a crucial role in shaping the early Church.

Christianity's message of hope and salvation, its promise of eternal life, and its emphasis on love and charity resonated with many people across the Roman Empire, particularly among the poor and marginalized.

Moreover, the faith's inclusivity—it was open to all, regardless of social status, gender, or ethnicity—made it appealing to a wide audience.

The first recorded state-sponsored persecution of Christians occurred in 64 CE under Emperor Nero, who blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome, leading to brutal executions in the Colosseum and along the streets of Rome.

Under Emperor Diocletian, the Great Persecution (303–311 CE) sought to eliminate Christianity through systematic destruction of churches, burning of scriptures, and executions, marking the last and most severe crackdown before the faith’s legalization.

A turning point in the history of Christianity came with the conversion of Constantine the Great, the Roman Emperor.

In 312 CE, before the Battle of Milvian Bridge, Constantine reportedly had a vision of the Christian symbol, which led him to fight under the Christian banner.

After winning the battle, Constantine attributed his victory to the Christian God and converted to Christianity.

This marked the beginning of a new era for the faith.

In 313 CE, Constantine, along with his co-emperor Licinius, issued the Edict of Milan, which granted religious tolerance for all religions throughout the empire.

This effectively ended the state-sponsored persecution of Christians and allowed the faith to be practiced openly.

Constantine also provided patronage to the Church, commissioning the construction of churches and promoting Christians to high-ranking positions.

In 325 CE, Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea in an attempt to resolve theological disputes and unify the Church.

The council established key tenets of Christian doctrine, clarified the nature of Jesus Christ, and set the date for the celebration of Easter.

It was a significant step towards the institutionalization of Christianity.

Becoming the only religion of the empire

The rise of Christianity from a persecuted sect to the state religion of the Roman Empire marked a significant turning point in the history of the faith.

This transformation was largely completed under the reign of Emperor Theodosius I, who ruled from 379 to 395 CE.

Theodosius I was a staunch Christian, and his reign was characterized by policies that favored Christianity and sought to marginalize pagan religions.

In 380 CE, he issued the Edict of Thessalonica, also known as the Cunctos populos, which declared Nicene Christianity as the state religion of the empire.

The edict called for all Roman citizens to profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria, essentially making Christianity the official and dominant religion.

Theodosius also took steps to suppress pagan worship and other forms of religious practice that were not aligned with Nicene Christianity.

He ordered the closure of temples, banned sacrifices, and prohibited other pagan rites and customs.

These measures, while controversial and often met with resistance, significantly diminished the influence of pagan religions and further strengthened Christianity's position within the empire.

As the state religion, Christianity underwent significant institutional development. The Church hierarchy became more structured, mirroring the administrative organization of the Roman Empire.

Bishops, who were often based in major cities, gained considerable authority and influence, not just in religious matters, but also in social and political affairs.

The patronage of the state also led to a boom in church construction. Magnificent basilicas were built in Rome, Constantinople, and other major cities, often on a scale that rivaled the grandest Roman buildings.

These served not only as places of worship, but also as centers of social and cultural life.

However, the establishment of Christianity as the state religion also brought challenges.

The close association between the Church and the state led to power struggles and corruption.

Moreover, theological disputes became intertwined with political conflicts, leading to schisms and violence.

The fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Church

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE marked the end of ancient Rome's political dominance, but it also signaled the rise of the Christian Church as a major institution in Europe.

As the Western Roman Empire crumbled, the Church emerged as a stabilizing force, providing continuity and structure amidst the chaos.

The decline of the Western Roman Empire was a gradual process that unfolded over several centuries, marked by political instability, economic decline, military weakness, and social fragmentation.

The repeated invasions by Germanic tribes, culminating in the deposition of the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, by the Germanic king Odoacer in 476 CE, marked the official end of the Western Roman Empire.

In the midst of this turmoil, the Christian Church stepped into the power vacuum left by the collapsing imperial authority.

The Church, with its well-established hierarchy and network of dioceses and parishes, provided a semblance of order and unity.

Bishops, particularly the Bishop of Rome—who would later become known as the Pope—gained considerable influence, often serving as mediators and administrators in addition to their religious duties.

The Church also played a crucial role in preserving knowledge and culture during this period, often referred to as the Dark Ages.

Monasteries became centers of learning, where monks copied and preserved ancient texts, including the Bible and works of Greek and Roman literature and philosophy.

This ensured that much of the intellectual heritage of the ancient world was not lost but was instead incorporated into the emerging Christian culture.

Moreover, the Church continued to spread Christianity throughout Europe. Missionaries traveled to various regions, converting the Germanic tribes that had settled in the former territories of the Western Roman Empire.

The conversion of these tribes, many of which established their own kingdoms, further solidified the Church's influence.

The Church turns on itself: The Great Schism

The history of Christianity is marked by theological debates, political conflicts, and cultural differences, which over time led to the formation of various Christian denominations.

One of the most significant events in this process was the Great Schism of 1054, which resulted in the split between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church.

The roots of the Great Schism can be traced back to the division of the Roman Empire into eastern and western halves in the 4th century CE.

This division led to differences in language, culture, and political structures between the East and the West, which in turn influenced the development of Christianity in these regions.

The Western Church, centered in Rome, used Latin and was closely tied to the political power of the Western Roman Empire and later the Holy Roman Empire.

The Eastern Church, with its center in Constantinople, used Greek and was closely connected to the Byzantine Empire.

Over the centuries, theological disagreements between the Eastern and Western Churches intensified.

These included disputes over the nature of the Holy Spirit, the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist, and the role of images in worship.

However, the primary point of contention was the issue of papal authority. The Western Church asserted the supremacy of the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, over all other bishops, while the Eastern Church maintained that all bishops were equal and rejected the Pope's claim to universal jurisdiction.

These tensions came to a head in 1054 in an event known as the Great Schism. Representatives of the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated each other, formalizing the split between the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.

This division, which persists to this day, was a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity.

The Great Schism was not the end of Christian fragmentation. In the centuries that followed, further splits occurred, particularly in the Western Church.

Fragmentation in the West: The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation, which began in the 16th century, was one of the most significant events in the history of Christianity.

It led to a profound shift in religious thought and practice, and resulted in the formation of numerous Protestant denominations, fundamentally altering the religious, political, and cultural landscape of Europe.

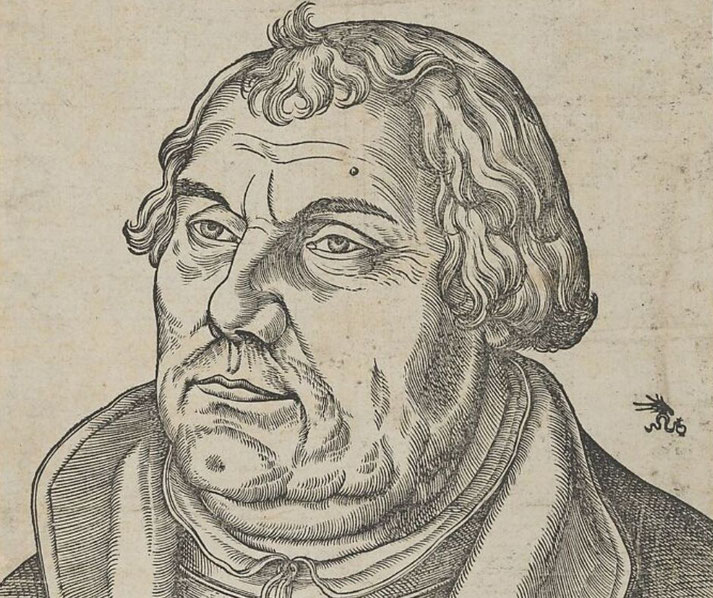

The Reformation was sparked by Martin Luther, a German monk and theology professor, who was deeply troubled by what he saw as abuses and corruption within the Roman Catholic Church, particularly the sale of indulgences, which were pardons for sins.

In 1517, Luther famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, a document that criticized the Church's practices and challenged its teachings.

Luther's primary contention was that salvation was achieved through faith in Jesus Christ alone, not by good works or the purchase of indulgences.

This doctrine, known as justification by faith alone, was a radical departure from the Catholic Church's teachings.

Luther also argued for the priesthood of all believers, asserting that all Christians had a direct relationship with God, and he championed the use of the vernacular in religious services, enabling people to read the Bible and participate in worship in their own language.

Luther's ideas quickly spread, thanks in part to the invention of the printing press, which allowed the mass production of his writings.

His teachings resonated with many people, leading to widespread support for the Reformation, particularly in Northern Europe.

Other reformers, such as John Calvin in Switzerland and Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich, also emerged, each contributing their own interpretations and innovations, leading to the formation of various Protestant denominations, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, and the Anglican Church.

The Catholic Church responded to the Reformation with the Counter-Reformation, a series of reforms and renewed missionary efforts aimed at addressing the criticisms of the Protestants and reaffirming Catholic doctrine.

The Council of Trent, which took place from 1545 to 1563, was an important part of this response, resulting in significant changes in the Church's practices and the affirmation of key Catholic doctrines, such as transubstantiation and papal authority.

The Reformation had far-reaching consequences, not just for Christianity, but for society as a whole.

It led to religious wars and conflicts, but also to greater religious pluralism and tolerance.

It influenced education, as Protestants established schools and universities to promote literacy and Bible reading.

It also had significant impacts on art, music, and literature, inspiring new forms of religious expression.

Christianity's struggles and success in the modern era

The modern era, from the Enlightenment to the present day, has been a time of significant change and development for Christianity.

The faith has continued to adapt and evolve in response to social, political, and intellectual shifts, demonstrating both its resilience and its capacity for transformation.

The Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, with its emphasis on reason, individualism, and skepticism of authority, challenged traditional religious beliefs and institutions.

Many Enlightenment thinkers criticized the Church for its perceived corruption and intolerance, and advocated for religious freedom and tolerance.

This led to significant changes in the relationship between the Church and the state, with many countries adopting policies of religious pluralism and separating religious institutions from government.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the expansion of Christianity beyond Europe and the Americas, largely due to European colonization and missionary efforts.

In Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, Christianity interacted with local cultures and religions, leading to the development of unique forms of Christian practice and belief.

At the same time, these interactions often involved conflict and coercion, and the legacy of colonialism continues to be a source of controversy within Christianity.

The modern era has also seen significant changes within Christian denominations.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), for example, led to major reforms within the Roman Catholic Church, including the use of the vernacular in the Mass, a greater emphasis on ecumenism, and a renewed focus on social justice.

Protestant denominations have also undergone changes, with debates over issues such as the ordination of women, the acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals, and the role of Christianity in social and political issues.

In the 21st century, Christianity faces new challenges and opportunities. The rise of secularism, particularly in Europe, has led to a decline in traditional religious belief and practice.

At the same time, Christianity is growing rapidly in regions such as Africa and Asia. The faith is also grappling with issues such as interfaith dialogue, the relationship between religion and science, and the role of religion in a globalized world.

How can the growth of Christianity be explained?

At its core, Christianity offers teachings—such as love, forgiveness, and the promise of eternal life—that have universal appeal.

The faith is open to all, regardless of ethnicity, social status, or gender, which has enabled it to cross cultural and geographical boundaries.

This universal message has been carried far and wide by dedicated missionaries. From the early apostles like Paul, who helped Christianity reach beyond Judea and into various parts of the Roman Empire, to modern missionaries who have established Christian communities around the globe, these individuals have played a crucial role in the spread of the faith.

Political support has also been instrumental in Christianity's growth. The conversion of Constantine the Great and the subsequent Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which granted religious tolerance throughout the Roman Empire, provided a significant boost to the faith.

In the Middle Ages, the Church served as a unifying force in Europe, and during the Age of Exploration, European Christian powers spread their faith to other parts of the world.

The institutional strength of the Church, with its structured hierarchy and established doctrines, has provided stability and continuity over centuries, while also playing a significant role in education, social services, and politics.

Christianity's adaptability has also contributed to its success, as it has allowed it to evolve in response to social, intellectual, and political changes.

In recent times, many Christian denominations have made efforts to engage with modern social issues, such as poverty, inequality, and environmental protection, ensuring the faith's ongoing relevance to contemporary life.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.