What was the Hundred Years' War?

The Hundred Years’ War was a series of conflicts from 1337 to 1453 between England and France. It included many battles, sieges, and diplomatic moves rather than one long continuous conflict.

But, what sparked this long war?

What were the causes of the war?

The main reasons for the war include claims to the French crown, disputes over land, and economic concerns.

Dynastic claims and the French throne

One of the most immediate causes of the Hundred Years' War was the disputed claim to the French throne.

Edward III of England, the grandson of Philip IV of France through his mother, Isabella, laid claim to the French crown after the death of Charles IV of France, Philip IV's last living son.

The French nobility, however, invoked the Salic Law, which prohibited succession through the female line, to disqualify Edward's claim.

Instead, they crowned Philip VI, a cousin of the deceased Charles IV, as the King of France.

This decision set the stage for a dynastic struggle that would last for over a century.

Territorial disputes: The Gascony flashpoint

Gascony, a region in southwestern France, was another major point of contention.

Although technically a fief of the French crown, Gascony had been under English control since the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II of England in the 12th century.

The region was economically significant for both nations; it was a major wine-producing area for France and a key trading partner for England.

When Philip VI tried to confiscate Gascony due to perceived disloyalty from Edward III, it provided the casus belli for the English to declare war.

Economic interests: The wool trade and Flanders

Economic factors also played a significant role in the onset of hostilities. The wool trade was the backbone of the English economy, and much of this wool was processed in the cloth-making towns of Flanders, a region under French suzerainty.

The English crown had a vested interest in ensuring that Flanders remained a reliable trading partner, free from French interference.

Attempts by the French to exert greater control over Flanders were viewed as direct threats to England's economic security.

The role of alliances

The complex system of European alliances also contributed to the escalation of the conflict.

The Kingdom of Scotland, traditionally an enemy of England, was allied with the French, leading to a two-front war for the English.

Similarly, various other European states were drawn into the conflict due to their existing treaties and obligations, further complicating the geopolitical landscape.

Key battles and turning points

The Hundred Years' War saw several key battles and turning points that shifted the balance of power between England and France.

Battle of Crécy (1346)

One of the earliest significant battles was the Battle of Crécy in 1346. Here, the English army, led by Edward III, used the longbow to devastating effect against the French cavalry.

The French forces relied on traditional medieval tactics and the crossbow, but were decimated.

The victory at Crécy shattered the myth of French invincibility and demonstrated the tactical superiority of the English longbow, which set the tone for future battles.

Battle of Poitiers (1356)

Another pivotal moment came a decade later at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. The English, under the command of Edward, the Black Prince, managed to capture the French King John II.

This led to a temporary cessation of hostilities and the signing of the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, which granted England significant territories in France.

However, the treaty was short-lived, and hostilities soon resumed.

Battle of Agincourt (1415)

The Battle of Agincourt in 1415 is one of the most famous battles of the war.

Led by Henry V, the English were heavily outnumbered but managed to pull off a stunning victory, thanks in part to the muddy conditions that hampered the French cavalry and the effective use of the longbow.

The battle was a significant morale booster for the English and led to Henry V's recognition as heir to the French throne through the Treaty of Troyes, although this was later contested.

Siege of Orléans (1428–1429)

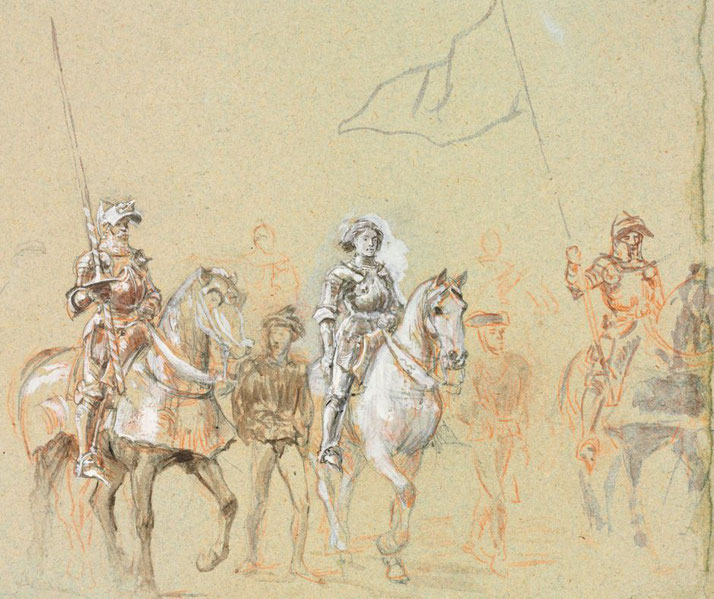

However, the tide began to turn in favor of the French with the Siege of Orléans between 1428 and 1429.

The French were on the brink of losing the strategically important city when Joan of Arc, a young peasant girl, claimed to have received guidance directly from God.

She convinced the Dauphin Charles (later Charles VII) to allow her to lead the French army.

Her presence revitalized the French troops, and they successfully lifted the siege.

This was a turning point in the war, since it reignited French hopes and led to several key victories that helped to slowly push the English out of France.

The end of the war and its consequences

The Hundred Years' War came to a close in 1453 with the French recapture of Bordeaux, a significant event that effectively expelled the English from France, except for the port city of Calais.

Social impacts

On the social front, the war had devastating effects on the populations of both countries.

The prolonged conflict led to widespread famine, disease, and economic hardship.

In France, the war had sparked social upheavals like the Jacquerie, a peasants' revolt fueled by the misery and taxation that the war had brought.

England experienced similar social unrest, most notably the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, which was partly a reaction to the heavy taxes levied to fund the war.

These revolts were brutally suppressed but signaled a growing discontent with the feudal system and the beginning of the end for serfdom.

Economic consequences

Economically, the war had a profound impact as well. The cost of maintaining armies and fortifications for over a century drained the coffers of both nations.

France's economy was particularly hard-hit, with many agricultural areas ruined by years of warfare.

England faced economic challenges too, including the loss of important French territories that had been lucrative trading partners.

Impacts on the royal houses of England and France

Politically, the end of the war had significant ramifications. In France, the victory solidified the power of the monarchy and helped forge a sense of national identity.

The Estates-General, an early form of a representative assembly in France, lost much of its power as the king centralized authority.

In England, the loss in the war and the subsequent decline in feudal revenues weakened the English monarchy, setting the stage for internal conflicts like the Wars of the Roses, which would plunge England into civil war for much of the latter half of the 15th century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.