Revelations from the East: The extraordinary journey of Marco Polo

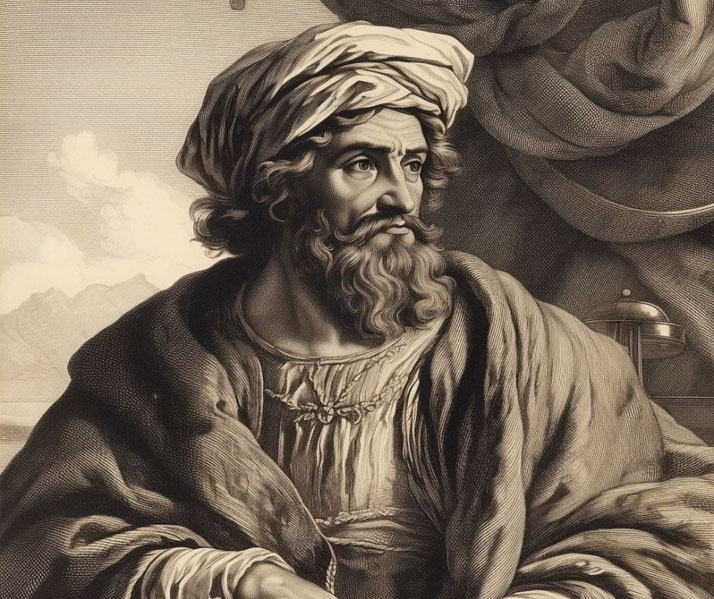

In the history of exploration and cultural exchange, few figures loom larger than Marco Polo. Born into a wealthy Venetian merchant family in 1254, Polo would go on to venture far beyond the confines of his native Europe, traversing vast and mysterious lands whose existence was but a whisper in the Western world.

His extraordinary journey – from the Byzantine grandeur of Constantinople to the distant court of the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, and beyond – would forever transform the European understanding of the world.

His vivid accounts of the far-reaching Silk Road and life under the Mongol Empire provided a window into a world that was otherwise inaccessible to his contemporaries.

Early life

Marco Polo was born in 1254 into a prosperous merchant family in the bustling city-state of Venice, a maritime republic known for its trade prowess, its intricate network of canals, and its diplomatic acumen.

It was this backdrop of mercantile ambition and maritime adventure that set the stage for Polo's later expeditions.

His father, Niccolò Polo, and uncle, Maffeo Polo, were pioneering merchants themselves.

Their initial journey to the East, during which they reached the court of Kublai Khan in China, was already steeped in family lore by the time of Marco's birth.

Niccolò had left his wife pregnant with Marco when he embarked on this journey, and would not return until his son was a teenager.

Due to these circumstances, Marco Polo's upbringing was marked by the absence of his father.

Raised by his mother until her death and then by extended family, he received a typical education of a Venetian gentleman, learning about classical literature, philosophy, the basics of bookkeeping, as well as the mercantile trade.

He also learned to read and write in Italian, and may have picked up some knowledge of sailing.

In 1269, when Marco was around fifteen years old, his father and uncle returned from the East with wondrous tales of distant lands and a mission from Kublai Khan himself.

Intrigued by their stories, young Marco found himself standing at the precipice of a vast unknown world, one he would soon come to know in great detail.

Marco Polo's journey to the East

In 1271, the Polo family - Marco, his father Niccolò, and his uncle Maffeo - embarked on a monumental journey that would span over 15,000 miles and nearly two decades.

The Polos' voyage was commissioned by Kublai Khan, the fifth Khagan of the Mongol Empire, who had requested they return with scholars and priests to teach Christianity and Western customs to his court.

Setting sail from Venice, they journeyed through the Mediterranean Sea and reached the rugged lands of the Middle East, following the established routes of the Silk Road.

They traveled through Armenia, Persia (modern-day Iran), and Afghanistan, across the Pamir Mountains and the formidable Taklamakan Desert, sometimes called "The Desert of Death".

Throughout this journey, young Marco Polo was introduced to a plethora of cultures and customs vastly different from his own.

He encountered various religious practices, a myriad of languages, and a diverse range of goods, enriching his understanding of the world with every step.

His exposure to the Silk Road, an essential artery of trade, communication, and cultural exchange between the East and West, was a significant aspect of his education as a traveler.

From the steppes of Central Asia, the Polos moved into the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in history.

There, they crossed paths with tribes and communities living under Mongol rule, witnessing first-hand the extent and influence of the empire.

After a grueling journey that lasted over three years, the Polos finally arrived at Kublai Khan's opulent court at Shangdu, also known as Xanadu, in 1275.

Marco Polo's exploration of Yuan China

Upon reaching the Mongol Empire, the Polo family was warmly welcomed by Kublai Khan.

His court in Shangdu was a place of unparalleled splendor, filled with the richness of many cultures.

Kublai Khan, impressed by young Marco's intelligence and perceptiveness, appointed him to serve in his court.

During his service, Marco undertook various administrative and diplomatic roles, even acting as a special envoy for the Khan.

These positions allowed him to travel across the vast stretches of the Mongol Empire, from Southeast Asia to India and possibly even Burma.

This period in the Mongol Empire was one of peace, prosperity, and cultural exchange, known as the Pax Mongolica.

Marco's keen observations during this period provided invaluable insights into the social, cultural, and political structures of the Eastern world.

He noted the Mongol's efficient postal system, their use of paper money, and the empire's system of public welfare, which included provisions for the care of the elderly and the poor.

Marco also wrote extensively about the grandeur of the cities he visited, such as Hangzhou, which he described as one of the most beautiful and luxurious cities in the world.

He noted the abundance of silk, spices, and precious stones, the likes of which were unknown in the West.

He described with awe the vast mountains of Tibet, the tropical richness of Burma, and the diverse cultures of India.

Return to Venice

After nearly 17 years in the court of Kublai Khan and traveling across the Mongol Empire, Marco Polo and his family began to long for their homeland, Venice.

The aging Khan had grown fond of the Polos and was initially reluctant to let them leave, but an opportunity soon presented itself that would allow for their departure.

In 1292, the Polos agreed to escort a Mongol princess, Kokachin, to Persia where she was to marry a Persian prince, a task that would allow them to finally return home.

Taking a different route from their initial journey, they embarked on a perilous two-year sea voyage that took them through the South China Sea, across the Indian Ocean, and through the Arabian Sea to the Persian Gulf.

The journey was filled with risks and dangers, including storms, diseases, and pirates.

Upon reaching Persia, they discovered that the Persian prince had died during their journey.

The princess was then married off to a local noble, and the Polos continued their journey overland, through Constantinople, and finally reached Venice in 1295.

Returning home after 24 years, they found Venice at war with Genoa. Their long absence and their Eastern attire led to them being initially unrecognized by their own family.

Yet, their tales of the Mongol Empire, their return laden with precious treasures, soon reinstated their status.

Tragically, soon after their return, the war with Genoa intensified, leading to Marco being captured and imprisoned during a naval battle in 1298, known as the Battle of Curzola.

The remarkable reason we have his life story

During Marco Polo's imprisonment, he came into contact with a fellow prisoner: Rustichello da Pisa.

Rustichello, a writer of romance novels, quickly became captivated by Marco's extensive tales of travel and adventure.

Recognizing the value and allure of these stories, he decided to help Marco record his experiences.

This collaboration resulted in "The Travels of Marco Polo", often known as "Il Milione", a collection of Marco Polo's travels and observations across the Mongol Empire and other Asian territories.

The account, filled with vivid descriptions of far-off lands, was unlike anything that had been seen in Europe at the time.

Marco's tales painted a picture of a world previously unimaginable to his contemporaries.

He detailed the wealth of the East, its majestic cities, the customs and cultures of its people, and the breadth of Kublai Khan's dominion.

Furthermore, his detailed observations on the political and administrative workings of the Mongol Empire, descriptions of commodities, currencies, and trade practices, as well as the depiction of the fauna, flora, and geography of the East, provided unprecedented insights into a world unknown to the West.

"The Travels of Marco Polo" became immensely popular, with manuscripts rapidly spreading throughout European territories.

Later life and death

Upon his release from Genoese captivity in 1299, Marco Polo returned to Venice, a city he had left as a teenager and only returned to briefly before his capture.

There, he took up the life of a Venetian merchant, living relatively quietly after the extraordinary adventures of his youth and early adulthood.

He married Donata Badoer, a woman from an old, respectable, but not particularly wealthy or influential, Venetian family.

Together, they had three daughters: Fantina, Bellela, and Moreta.

He spent much of his later years managing his household, participating in local events, and likely sharing tales of his travels with an ever-eager audience.

Marco Polo also continued his business ventures, establishing himself as a well-respected figure in the local merchant community.

It is known that he owned several trading vessels and was a prominent figure in the local commodities market.

His business dealings and his family's historical involvement in the Asiatic trade likely made him a wealthy man, providing a comfortable life for his family.

On January 8, 1324, Marco Polo passed away after falling ill. On his deathbed, he was asked to recant his stories, to admit that they were falsehoods concocted from hearsay and imagination.

His response was resolute: "I did not tell half of what I saw, for I knew I would not be believed."

Marco Polo's impact on exploration

Marco Polo's detailed descriptions of the lands, cultures, and resources of Asia had a significant influence on European cartography and exploration.

Before his accounts, maps of Asia were based largely on conjecture and mythology, and Europe's understanding of the world was centered primarily on its own continent.

Polo's book provided cartographers with a wealth of new and detailed geographic information.

He described landscapes, cities, and routes with such precision that his accounts became a crucial reference for mapmakers.

These descriptions, coupled with tales of the immense wealth and resources of the East, created a more accurate and intriguing picture of Asia, sparking a surge of interest and exploration.

Among the most notable of these were the Catalan Atlas of 1375 and the Fra Mauro map of 1459.

The Catalan Atlas, created by Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques, was one of the most advanced world maps of its time.

It incorporated much of Polo's information, especially his descriptions of China and Southeast Asia.

Similarly, the Fra Mauro map, a comprehensive mappa mundi, used Polo's accounts as a significant source, accurately depicting Asian geography and reflecting the rich culture and prosperity of the East.

Beyond cartography, Marco Polo's influence extended to the exploration itself. His accounts stirred the curiosity and ambitions of explorers, prompting them to see these foreign lands for themselves.

Christopher Columbus, inspired by Polo's descriptions of the wealth of the East and seeking a quicker route for trade, embarked on his voyage that eventually led to the discovery of the New World.

Columbus even had a copy of Polo's book among his possessions, using it as a guide and a source of inspiration.

Ongoing criticisms of Marco Polo's account

While Marco Polo's travels have captivated the imagination of the world for centuries, his accounts have also been the subject of considerable controversy and debate.

Many of these disputes arise from the seeming implausibility of certain elements of his narrative and the lack of specific mentions of significant cultural aspects in his accounts.

One of the most frequently cited points of contention concerns Polo's silence on certain distinctly Chinese cultural aspects.

For instance, Polo does not mention the Great Wall of China, tea, or chopsticks, all central elements of Chinese culture.

This silence led many scholars to question whether he ever visited China at all.

However, other historians argue that the Great Wall as we know it today did not exist in Polo's time, and tea, although consumed widely in China, might not have been a noteworthy aspect for Polo.

The descriptions of fantastical beasts and mythical figures, like the gigantic bird, the roc, and the Christian monarch Prester John, have also led some to dismiss Polo's account as imaginative fiction.

Others, however, argue that these could be misinterpretations or exaggerations of real phenomena or figures, not uncommon in medieval travel literature.

Marco Polo's detailed descriptions of the opulence of the Mongol Empire and the immense wealth of the East have also been met with skepticism.

However, these descriptions align with other historical accounts of the era and could be attributable to Polo's desire to communicate the exoticism and grandeur of the East to his audience.

Moreover, the absence of Marco Polo's name in Mongolian and Chinese records has been cited as evidence against his claims.

However, supporters argue that such omission is not conclusive proof against his presence, considering the vast size of the Mongol Empire and its administrative complexity.

While these controversies persist, there is no denying the profound influence of Marco Polo's accounts on the European perception of the East and the subsequent push towards exploration.

Whether entirely accurate or sprinkled with exaggeration, Marco Polo's accounts remain a valuable chronicle of 13th-century Asia through the eyes of a Westerner, forever enshrined in the annals of exploration and discovery.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.