The mysterious disappearance of the Maya civilization: what happened to them?

The Maya civilization, known for their extraordinary developments in writing, mathematics, and astronomy, remains a subject of enduring fascination.

However, equally captivating, and considerably more enigmatic, is the question of its disappearance. The transition from monumental grandeur to cryptic silence has puzzled archaeologists, historians, and enthusiasts for generations, marking one of the most tantalizing mysteries of the ancient world.

At their zenith, they had established a complex society, spanning across what is today Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, Belize, and parts of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

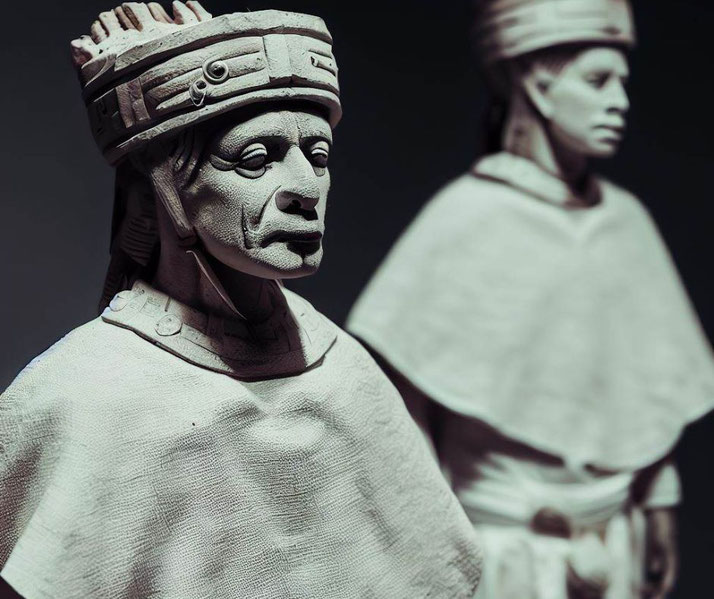

They constructed monumental cities with towering pyramids, developed a sophisticated hierarchical political structure, and cultivated a rich and intricate mythology.

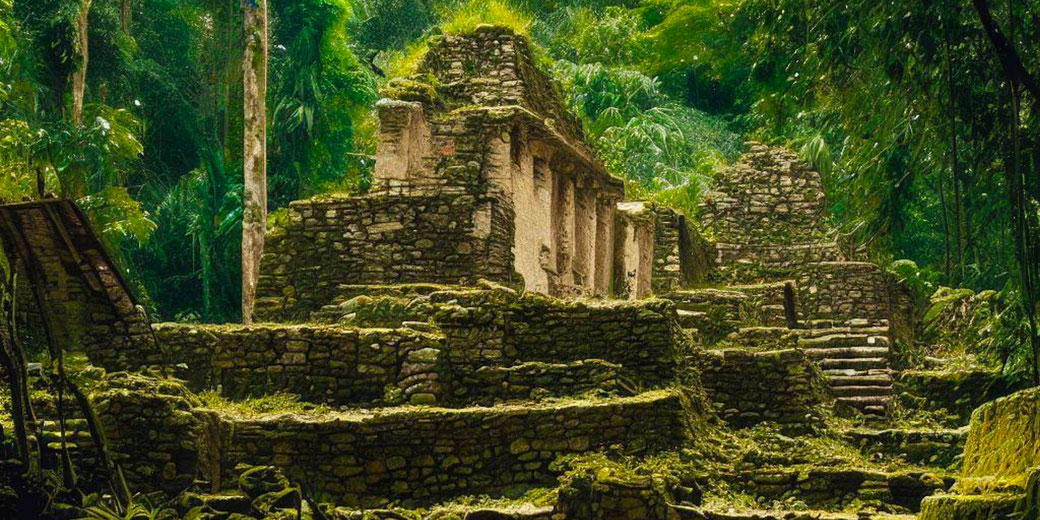

However, by the time Spanish conquistadors set foot in the Americas in the 16th century, the great cities of the Maya had been abandoned for centuries, retaken by the jungle.

What could have led to the dramatic decline and disappearance of such a potent civilization?

Was it warfare, famine, drought, disease, political discord, or a combination of these factors?

The rise of the Maya civilization

The Maya civilization's origins stretch back thousands of years, with the first settled villages established around 1800 BCE in the Soconusco region, along the Pacific coast.

These early Maya people were primarily agriculturists, cultivating staples like maize, beans, and squash.

Over time, their communities grew in size and complexity, leading to the birth of the Preclassic or Formative Period, which spanned from 2000 BCE to 250 CE.

During this time, the Maya developed the foundations of their culture, including a hierarchical society, a pantheon of deities, and a unique style of architecture.

They began constructing ceremonial centers featuring large platforms and temples.

This was also the time when the Maya started developing their intricate system of writing, initially through simple symbolic representations, which evolved into a complex combination of glyphs representing sounds and ideas.

The Classic Period, running from 250 CE to 900 CE, witnessed the apogee of the Maya civilization.

They constructed grand cities, like Tikal, Palenque, Copán, and Caracol, where they erected towering pyramids, ornate palaces, and astronomically aligned temples.

These were bustling urban centers, housing thousands of residents and playing host to complex political and economic activity.

The Maya made significant strides in arts, science, and technology during this period.

They perfected the art of writing and used it extensively to record historical events, astronomical observations, and religious rituals.

They also developed a sophisticated mathematical system, with the concept of zero, and an elaborate calendar system intricately tied to their cosmology and religious beliefs.

Their achievements in astronomy were particularly impressive, with the Maya accurately charting the movements of celestial bodies, aiding them in agricultural planning and religious ceremonies.

The first signs of trouble

The decline of the Classic Maya civilization, often referred to as the "Maya Collapse," was not a singular cataclysmic event but rather a series of setbacks unfolding over centuries.

The first signs of trouble arose in the southern lowland cities during the 8th and 9th centuries CE.

One of the most conspicuous indications of trouble was the sudden halt in the construction of monumental architecture and the cessation of the elaborate historical inscriptions that had been a hallmark of the Classic Maya.

The final Long Count calendar date recorded in the Southern Maya area was in 909 CE at Toniná, a city in present-day Chiapas, Mexico.

After this, no more grand temples or stelae were built, and the previously bustling cities slowly fell into ruin and were reclaimed by the jungle.

Warfare and political instability were significant contributors to this decline. The Classic Period was marked by increasing conflict, with numerous records of battles and capture of rulers between city-states.

These wars may have been driven by competition for resources, especially as overpopulation put stress on food and water supplies.

There is evidence of fortified cities and burnt palaces, suggesting widespread violence.

These conflicts would have disrupted trade routes and agricultural production, further destabilizing the region.

By the end of the 10th century, many of the great Classic Maya cities had been abandoned, and the focus of the Maya civilization had shifted to the northern regions, particularly the Yucatan Peninsula.

Here, new cities like Chichen Itza and Mayapan continued the Maya traditions, albeit in a modified form.

What caused the rapid collapse?

The enigmatic decline and eventual disappearance of the Classic Maya civilization has been the subject of much debate among researchers.

Multiple theories have been proposed, often focusing on environmental, social, or disease-related factors, or a combination thereof.

One of the most prominent theories is centered around environmental changes, particularly climate change and drought.

Paleoclimatic studies have suggested that a series of prolonged, severe droughts struck the Maya lowlands during the Terminal Classic Period (800-950 CE).

These dry spells, perhaps intensified by deforestation due to the Maya's agricultural practices, could have led to crop failures and water shortages, straining the densely populated cities.

Another environmental theory focuses on the consequences of intensive agriculture.

To sustain their growing populations, the Maya may have overexploited their agricultural land and caused widespread deforestation, leading to soil degradation.

These agricultural practices could have made their food supply increasingly precarious, particularly in combination with periods of drought.

Social factors also played a significant role, according to many theories. Overpopulation could have put severe strain on resources, leading to competition and conflict over food and water.

The complex system of city-states, each with their own rulers and dynasties, may have added to the instability, leading to frequent wars.

These conflicts, often recorded in their own inscriptions, disrupted trade and could have led to political collapse.

Epidemics and diseases form the basis of another set of theories. It's possible that the crowded urban centers, combined with the malnutrition and weakened immune systems resulting from food shortages, could have allowed diseases to spread rapidly and take a heavy toll on the population.

Many researchers now believe that it was not a single factor, but a combination of these environmental, social, and health-related stresses that led to the decline of the Maya cities.

A period of drought or a severe epidemic could have been the tipping point for a society already under strain from overpopulation, resource depletion, and warfare.

How archaeology has found answers to these questions

To support theories of climate change and drought, researchers have turned to paleoclimatic data from sources like lake and cave sediments, as well as stalagmites.

These records often show a decrease in rainfall during the period of the Maya collapse, which would have had serious impacts on their largely agrarian society.

Further evidence comes from the remains of ancient Maya water storage systems. In cities like Tikal, these reservoirs show signs of significant sediment buildup towards the end of the Classic period, suggesting longer and more frequent periods without rain.

The evidence of deforestation and soil degradation comes from pollen records and soil samples.

The pollen in ancient layers of lake sediment shows a decrease in tree species and an increase in grasses and weeds around the time of the collapse, suggesting widespread deforestation.

Soil samples often reveal signs of erosion and nutrient depletion, indicating over-farming.

The signs of social disruption, including warfare and overpopulation, are evident in the archaeological remains of Maya cities.

There is evidence of burnt buildings and increased fortifications, suggesting a rise in violence.

Some monuments depict scenes of warfare and record the capture of enemy rulers, pointing towards a time of political unrest.

Signs of overpopulation come from the size and density of residential buildings in the cities.

For example, Tikal, at its peak, had a population density comparable to some of the most densely populated cities today.

This density suggests the city was supporting a large population, which could have put pressure on resources and made it more vulnerable to other stresses like drought.

While direct evidence of disease is harder to find, some clues suggest health problems within the population.

Skeletal remains occasionally show signs of malnutrition, disease, or physical trauma.

Some researchers have suggested that a decline in the quality and quantity of grave goods during the late Classic Period could indicate a society under stress.

The Maya today

Despite the collapse of their great cities during the Classic Period, the Maya people did not vanish into the annals of history.

They continued to live, adapt, and influence the world in profound ways, and their descendants carry on many of their traditions today.

When the Spanish arrived in the Americas in the 16th century, they encountered a thriving Maya civilization in the northern Yucatan Peninsula.

Cities like Mayapan, Uxmal, and Chichen Itza, though not as grand as their Classic Period predecessors, still held significant influence.

However, the Spanish conquest brought drastic changes, with many Maya forcibly converted to Christianity and their written records destroyed.

Despite these challenges, the Maya people proved resilient. They continued to cultivate their lands, practice their crafts, and pass down their stories and traditions.

Elements of the ancient Maya religion were preserved, often syncretized with Christian beliefs.

The Maya language also endured, with millions of speakers today across Mexico and Central America, making it one of the most widely spoken indigenous languages in the Americas.

Today, the Maya play a crucial role in maintaining the cultural diversity of the region.

They continue to practice traditional agriculture, including the milpa system of rotating maize, beans, and squash.

Their skills in weaving and pottery are admired worldwide, with vibrant textiles and intricate ceramics reflecting a rich cultural heritage.

Archaeological sites like Tikal, Palenque, and Chichen Itza are now important cultural heritage sites, attracting visitors from around the world.

These ancient ruins serve as a testament to the grandeur of the Maya civilization and offer valuable insights into their complex society and beliefs.

In addition, contemporary Maya people have been active in asserting their rights and maintaining their distinct cultural identities.

They have been involved in political movements advocating for indigenous rights, land rights, and cultural preservation.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.