Feasting on peacock and porpoise: The weird world of medieval cuisine

From the sprawling farms of the peasantry to the opulent banquets of the nobility, food in the Middle Ages was as varied as it was intriguing.

This period, stretching roughly from the 5th to the 15th century, was marked by a distinct culinary culture that not only reflected the socio-economic conditions of the era, but also exemplified the tastes, beliefs, and customs of the people.

Yet, when one ventures deeper into the annals of medieval cuisine, they uncover a fascinating array of dishes that, to the modern palate, might seem quite strange.

The Middle Ages have long held an enchanting allure, filled with knights, castles, and a charming simplicity of life. Yet behind the romanticized veneer lies a complex world of food that was much more than just sustenance.

It was a statement of status, an assertion of cultural identity, and at times, a canvas for artistic expression. The cuisines ranged from the mundane to the extravagant, the predictable to the bizarre, and the simple to the complex.

How food was understood in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages, also known as the medieval period, was a thousand-year epoch marked by vast changes in society, economy, and culture.

It was a time when feudalism held sway, where kings, queens, knights, and serfs each had distinct roles in society, and these roles greatly influenced what they ate and how they ate it.

In general, the diet of the medieval people was based on what could be grown, hunted, or fished locally.

This resulted in a considerable variance in what people ate, influenced by factors such as geography, climate, and seasonality.

For instance, those in coastal regions might have had greater access to fish, while those in fertile valleys could cultivate an abundance of crops and raise livestock.

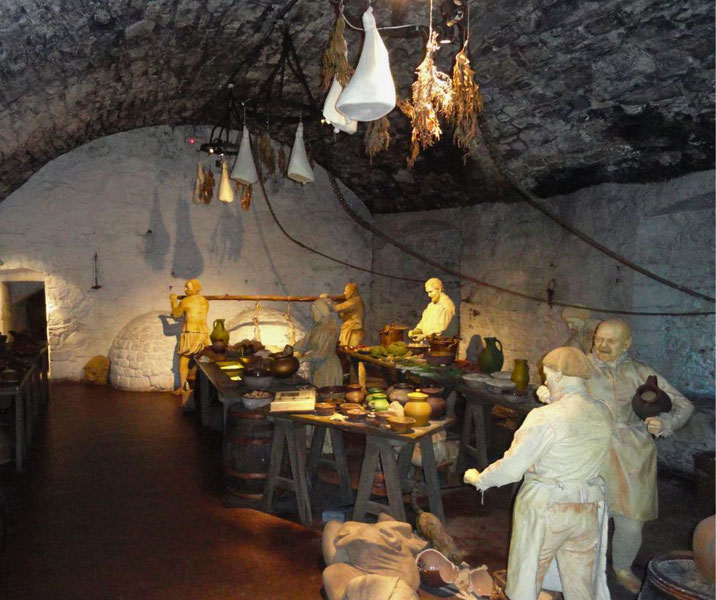

Feasting was a prominent feature of medieval life, particularly for the nobility and royalty. These meals were not just about food, but were elaborate events demonstrating wealth, power, and status.

The dishes were crafted to impress, often featuring exotic ingredients, complex preparations, and ornate presentations.

Simultaneously, these grand feasts also showcased the skill of the cooks and the bounty of the kingdom.

On the other end of the spectrum, the lower classes, which included the peasantry and the serfs, had a simpler and more monotonous diet.

It was largely grain-based, with barley, oats, and rye making up a significant part of their meals.

Vegetables, legumes, and a limited variety of fruits were consumed, while meat was usually a rarity, reserved for special occasions.

How diets varied in different parts of medieval Europe

In the vast expanse of the Middle Ages, food and culinary habits were greatly influenced by geographical location.

From the chilly territories of the northern realms to the sunny landscapes of the Mediterranean, the available resources and climate significantly shaped the regional diets, often leading to dishes and ingredients that would appear quite odd to modern sensibilities.

In the colder regions of Northern Europe, for instance, preserving food for the harsh, long winters was a necessity.

This led to an array of preservation methods, such as smoking, drying, and fermenting.

The Scandinavians developed lutefisk, dried whitefish, normally cod, treated with lye, which gave it a peculiar jelly-like consistency.

Similarly, pickled herring and other fermented fish became staples of the Nordic diet.

In these lands, game meats such as reindeer and wildfowl were also frequently consumed.

In contrast, the Mediterranean regions with their sunnier climes and fertile soils boasted a diet rich in fresh fruits and vegetables.

Olives, grapes, figs, and an assortment of greens featured prominently on the plates of those living around the Mediterranean Sea.

However, the uniqueness of this diet was highlighted by the use of certain pungent ingredients such as garum, a fermented fish sauce that Romans loved and which continued to be used in the Middle Ages.

It was a condiment with an exceptionally strong flavor and aroma, which may seem rather overpowering to many today.

In the British Isles, access to both the sea and inland resources led to a mix of marine and terrestrial diets.

Besides common grains and vegetables, medieval Britons had a liking for eels, and lampreys, a type of jawless fish, which were considered a delicacy.

Further East, the rich spice routes introduced the Middle Eastern and Asian tastes to medieval European cuisine.

Spices like cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and pepper began to appear more frequently in the food of the wealthy, adding an exotic flavor that became quite desirable.

The strangest foods eaten in the Middle Ages

As we venture further into the gastronomical narrative of the Middle Ages, we encounter a myriad of dishes and ingredients that, to our modern palates, may seem downright peculiar.

A particularly fascinating category of food is the array of unusual meats that were consumed. Besides the standard fare of chicken, pork, and beef, a wide variety of wild game graced the tables, particularly of the wealthy.

Peacock, heron, swan, and even porpoise were considered exotic delicacies. Roasted peacock, for instance, was often served at grand feasts, sometimes even presented in its plumage as a display of opulence.

Spices and flavors used in medieval dishes were quite varied, and sometimes a little strange.

An important ingredient in many recipes was a sauce called 'verjuice', made from unripe grapes or crab-apples, which added a sour flavor to many dishes.

Spices, considered a luxury item, were used extensively by the affluent, with one of the most peculiar being grains of paradise, a peppery spice native to West Africa.

Sweet and savory combinations were common. Meat dishes often included fruits, sugar, and spices to create a complex flavor profile.

For instance, a popular medieval dish was 'blancmange', a type of stew usually made from chicken, rice, sugar, and almond milk.

The season of Lent also inspired some strange food creations. As meat was forbidden during this period, imaginative alternatives were sought.

Almond milk was used as a substitute for animal milk, while fish became a primary source of protein.

Even more peculiar, certain aquatic birds, like puffins, were classified as 'fish' by the Church to provide more variety during Lent.

Why medieval people used food as medicine

Food and health were intrinsically linked in the Middle Ages, much like they are today.

However, the understanding of this connection was vastly different, largely governed by the humoral theory of medicine, prevalent during this period.

This theory, inherited from ancient Greece, proposed that the human body was made up of four humors - blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm - and that maintaining a balance of these humors was crucial to good health.

Food played a pivotal role in this balance. Each food, according to this theory, was believed to possess one of four qualities - hot, cold, wet, or dry.

These qualities had nothing to do with the physical temperature or moisture of the food but were linked to their perceived effects on the body.

For instance, red meat was considered 'hot' and 'dry', while fish was considered 'cold' and 'wet'.

Individuals were advised to eat according to their personal humoral constitution and the current season.

The medieval diet was also punctuated by several foods that were believed to possess healing properties.

Certain herbs, spices, and other ingredients were considered medicinal, often incorporated into dishes to promote health and wellbeing.

Honey was frequently used as a sweetener, but also recognized for its antimicrobial properties.

Sage was thought to improve memory, and ginger was believed to aid digestion.

One notable example of medicinal food was 'theriac', a compound of several ingredients, including opium, myrrh, and viper's flesh.

This was considered a universal antidote and was used extensively. Another peculiar health remedy was 'garum', the fermented fish sauce imported from the Mediterranean, which was believed to have health benefits, despite its strong smell.

Moreover, certain dietary practices were followed as part of disease prevention and treatment.

Fasting, for instance, was not only a religious practice but was also considered beneficial for health.

It was believed that is helped to cleanse the body of diseases and restore the balance of the humors.

The role religion played in food choices

In the Middle Ages, the spheres of the sacred and the everyday were deeply intertwined, and food was no exception to this.

Both religious doctrines and popular superstitions exerted a strong influence on what people ate, how they ate it, and when they ate it.

Christianity, being the dominant religion in Europe during the Middle Ages, had a profound impact on dietary habits.

The liturgical calendar was punctuated by numerous feast days and periods of fasting, each dictating specific food practices.

During the 40-day period of Lent, for instance, all animal products were prohibited, which led to the creation of various substitutes, including the extensive use of almond milk and stockfish.

Similarly, during Advent, fasting was practiced on certain days, and more fish and vegetarian dishes were consumed.

Certain foods were specifically associated with religious celebrations. At Christmas, a boar's head was traditionally served as a symbol of sacrifice and abundance.

Simnel cake, a fruitcake with layers of almond paste, was associated with Mothering Sunday in the British Isles, a day in Lent when people visited their 'mother' church.

Superstition also played a significant role in shaping food practices. Certain foods were considered lucky or protective.

For example, it was commonly believed that carrying a bit of bread saved from a meal could protect one from harm.

Similarly, ale was often blessed to ward off evil spirits before it was consumed.

The 'Doctrine of Signatures', a popular belief during this time, proposed that the physical appearance of a plant indicated its healing properties.

For instance, walnuts, because of their resemblance to the human brain, were believed to be beneficial for brain ailments.

Even the way food was consumed was influenced by superstition. For example, it was considered bad luck to overturn a loaf of bread, to spill salt, or to leave a plate of food unfinished.

The art and gaudiness of medieval feasts

Feasting was a cornerstone of medieval social life. Whether to mark religious observances, celebrate victories, or commemorate special occasions, feasts were grand affairs that demonstrated wealth, power, and status.

The dishes served at these events were as much about spectacle and entertainment as they were about satisfying hunger.

A grand medieval banquet was a lavish spectacle. Tables were laden with multiple courses, featuring a bewildering variety of dishes.

The practice of disguising food was also popular during these events. Cooks would often prepare dishes to look like something else entirely, such as shaping a meat pie to look like a fruit, or crafting a sweet dessert to resemble a roast.

Another oddity was the 'cockentrice' - a dish created by sewing the front of a piglet and the rear of a capon together, then roasting the resulting creature to amaze the banquet guests.

One of the most elaborate aspects of a medieval banquet was the presentation of 'sotelties' or 'subtleties', intricate edible sculptures that were meant to entertain and amuse guests between courses.

These creations, often made of sugar paste, marzipan, or gelatin, depicted scenes from religious, historical, or chivalric narratives.

They were a testament to the medieval love of spectacle and storytelling.

Drinks, too, were not without their quirks. A variety of ales, meads, and wines were commonly served.

One unusual concoction was 'Hippocras', a spiced wine named after Hippocrates, which was often served at the end of a feast and believed to aid digestion.

Can we recreate medieval foods today?

As we seek to understand the Middle Ages through the lens of food, there is a growing interest in recreating medieval recipes in modern kitchens.

These culinary time-travels provide us not only a hands-on (and mouth-on!) experience of history but also offer interesting insights into the evolution of our food culture and taste preferences.

Modern attempts to recreate medieval food often start with deciphering medieval cookbooks, or 'Forme of Cury' as they were known.

These recipes, however, come with their own set of challenges. They usually lack specific measurements, have unfamiliar terminology, and often call for ingredients that are hard to source or are no longer consumed.

Nevertheless, these difficulties have not deterred food historians and cooking enthusiasts from bringing medieval dishes to life.

Some recreations focus on the extravagant subtleties, like the gilded peacocks or the mythical cockentrice, primarily for their artistic and dramatic appeal.

Others attempt to recreate the daily fare of the average medieval person, such as pottage (a kind of thick stew made from grains, legumes, and vegetables), bread, and ale.

These recipes, albeit less glamorous, offer a taste of the mundane realities of medieval life.

There are even some food establishments and festivals today that offer a medieval dining experience, complete with period-appropriate dishes, utensils, and entertainment.

These provide an immersive way to explore the medieval past and its idiosyncratic gastronomy.

Recreating medieval food is about more than just replicating old recipes. It's about engaging with history in a tangible, sensory way.

It's about understanding our culinary roots and the journey our food culture has taken over the centuries.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.