The harsh realities women faced in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, which lasted for roughly 1000 years, from about 5th to the 15th century, a rigid structure was imposed on the lives of most women.

As a result, they experienced many challenges. Yet, in the face of these daily struggles, women played crucial roles in maintaining households, contributing to economies, and even influencing wider cultural developments.

How life was different for rich and poor women

During this period, many women belonged to the peasantry, where life was harsh and labor-intensive.

These women worked alongside men in the fields, tending to crops and livestock, which was essential to agricultural productivity.

In addition, they also engaged in domestic tasks like baking, brewing, and cloth-making, which were vital to their households' survival.

For some women, economic power came through trade and craft guilds. In cities like Paris and London, female artisans and merchants, such as the silk-weavers, played key roles in local economies.

They contributed to their families' income and sometimes managed their businesses.

For those women born into wealthy noble families, they enjoyed certain privileges and held significant influence within their households and sometimes beyond.

They often managed large estates, oversaw agricultural production, household staff, and finances.

They played crucial roles in maintaining the economic stability of their lands, especially when their husbands were absent due to war or political duties.

Yet, they still faced restrictions compared to their male counterparts.

Medieval marriage

The practice of arranged marriages was very common in the Middle Ages, particularly in the upper classes.

This is where two families formed alliances to strengthen familial ties and consolidate wealth, which was confirmed by the marriage of one person from each family.

These arrangements often included a dowry, a transfer of parental property, wealth, or gifts given to the groom's family.

For noble families, a substantial dowry could enhance social standing and secure political alliances.

In contrast, peasant marriages were much simpler. These were often based on practical considerations rather than wealth or alliances.

The bride and groom typically brought fewer material resources into the union, yet they worked together to sustain their household.

Medieval women and the law

In the Middle Ages, women’s legal rights and their interactions with the law were heavily influenced by their social status and marital status.

The concept of "coverture" was fundamental in determining a married woman's legal standing.

Under coverture, a woman's legal rights and obligations were subsumed by her husband's upon marriage, which limited her ability to own property, enter contracts, or represent herself in legal matters.

This system effectively rendered a wife legally invisible and dependent on her husband.

Widows, however, experienced a different legal status. They could own property, manage estates, and sometimes engage in legal disputes.

For example, the widow of a nobleman might act as the head of her household, overseeing land and tenants until her children came of age.

Unmarried women, or 'femme sole', had the ability to conduct business, own property, and enter contracts independently.

These women often found more freedom and autonomy than their married counterparts.

Women of the lower classes generally had fewer legal protections and faced harsher consequences under the law.

Peasant women, for instance, were subject to the jurisdiction of manorial courts, which handled local disputes and offenses.

These courts often enforced traditional gender roles and expectations, leaving women with limited recourse in legal matters.

Could women read and write in the Middle Ages?

Education and literacy in the Middle Ages were primarily reserved for the elite, with significant gender disparities.

By the 12th century, literacy rates among women were exceedingly low, particularly outside the nobility and monastic communities.

Only about 1% of medieval women were literate. However, noblewomen and nuns had better educational opportunities.

For instance, Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine abbess, became renowned for her theological, scientific, and musical writings.

Her works illustrate that, within convents, some women received extensive education.

Approximately 20% of noblewomen could read and write, often learning Latin to engage with religious texts and manage estates.

In contrast, peasant women rarely had access to education, and focused instead on household and agricultural duties.

This lack of formal schooling kept literacy rates exceptionally low among this social group.

However, some merchant and artisan women learned basic literacy and numeracy to assist in family businesses.

These skills, though limited, enabled them to keep accounts and correspond with customers.

Formal colleges and institutions like the University of Paris and Oxford University did not admit women.

Any woman who sought intellectual pursuits often needed male relatives or patrons to support their efforts.

Wealthy figures like Christine de Pizan could still become very well educated. De Pizan, for example, produced influential works in the 14th and 15th centuries, including The Book of the City of Ladies, which advocated for women's education and intellectual contributions.

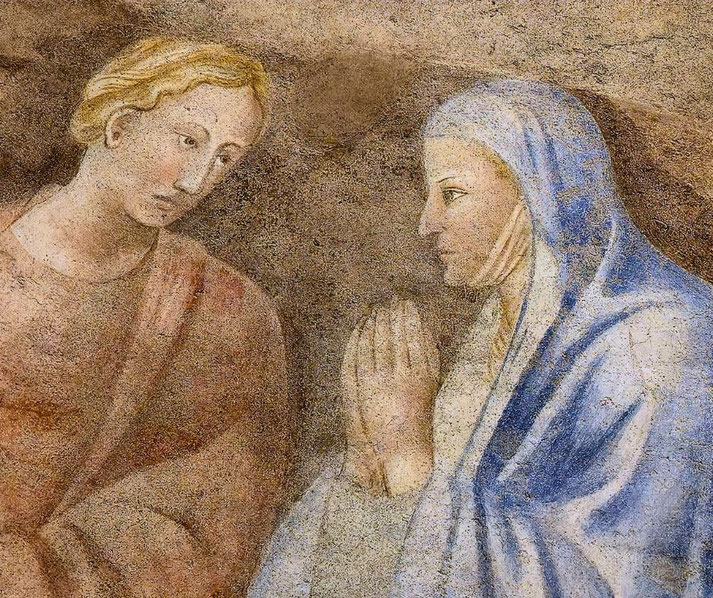

Women and the church

The Catholic Church was a dominant force in medieval society, which dictated much of daily life and moral expectations.

To the surprise of many modern observers, women had a strong presence in religious life of the time.

In particular, convents provided women with an alternative to marriage and a space for spiritual and intellectual pursuits.

For example, Clare, a follower of Francis of Assisi, founded the Order of Poor Ladies, known today as the Poor Clares, which emphasizes a life of poverty and prayer.

There was also the concept of 'anchorite' or 'anchoress' that referred to a woman who chose to live in seclusion for religious reasons.

These women, like Julian of Norwich, withdrew from secular life to dedicate themselves to prayer and contemplation. Julian, an anchoress in Norwich, wrote Revelations of Divine Love, the earliest known book in English written by a woman.

For ordinary women not living in religious communities, they could also engage in spiritual practices.

Pilgrimages were a popular form of religious devotion, which allowed women to travel to holy sites like Canterbury or Santiago de Compostela.

Margery Kempe, for instance, undertook numerous pilgrimages, seeking spiritual growth and expressing her fervent religious devotion through her writings and travels.

Powerful women in the Middle Ages

Despite the patriarchal structures that dominated society, there were a number of important examples where women were able to wield considerable power and influence in Europe.

In particular, noblewomen, queens, and female regents played crucial roles in politics. The best example is perhaps Eleanor of Aquitaine.

As the Duchess of Aquitaine and Queen consort of both France and England, she exerted considerable influence over two of the most powerful kingdoms of the time.

In particular, Eleanor actively participated in political decisions, supported her sons' rebellions against their father, King Henry II, and played a crucial role in the administration of her vast territories.

Similarly, Isabella of France, known as the 'She-Wolf of France', was another formidable political figure.

As the Queen consort of England, she led a successful invasion against her husband, King Edward II, which resulted in his deposition.

In the Iberian Peninsula, Queen Isabella I of Castile demonstrated extraordinary political acumen.

She, alongside her husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon, unified Spain and sponsored Christopher Columbus's voyage to the New World, which had far-reaching implications for global history.

Even in the Byzantine Empire, Empress Theodora, wife of Emperor Justinian I, wielded significant influence over state affairs.

Her political savvy and support of women's rights, including anti-trafficking laws, demonstrated her impact on both political and social reforms.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.