The extraordinary rise of Pachacuti and the birth of Tahuantinsuyu

If we could say anything about Pachacuti, the most famous of all of the Inca rulers, it is that he did not wait for greatness to find him. He seized it with almost a calculated precision.

Even though he inherited a kingdom under the very real threat of collapse, he rallied his forces, crushed the invaders, and claimed the throne.

Even more, he did not settle for survival but then expanded Inca rule beyond the valleys of his ancestors and built an empire that stretched across mountains, rivers, and deserts.

His name meant ‘earth-shaker’, which seems to have suited his character perfectly, because no ruler before him had changed the Andes so dramatically.

How did Pachacuti rise to power?

The young Pachacuti was born into the ruling dynasty of the Inca people which claimed to be able to trace its origins to Manco Cápac, the legendary founder of Cusco.

His father was Viracocha Inca, who had ruled over a modest but expanding kingdom in the Andean highlands.

At the time, the Incas only controlled a small region centered around Cusco. As such, they were not a dominant force and their survival as a people remained quite precarious.

In fact, the neighboring groups such as the Chanca, the Ayarmaca, and the Lupaca had continually contested the Inca’s presence in the region.

The different groups each wanted to take control over various trade routes and fertile valleys.

However, it appeared that Pachacuti’s father initially favored his brother, Inca Urco, for the throne.

Before Pachacuti assumed power, the Inca state faced a dangerous threat from the expansionist Chanca people, who assembled a formidable army to seize the city of Cusco.

Rather than defending the city, Viracocha Inca withdrew to the safety of Calca and left Inca Urco to organize a resistance, which he failed to do.

In the absence of clear leadship and recognizing the urgency of the moment, Pachacuti took command without his father’s approval.

He rallied warriors from Cusco and other nearby settlements by drawing upon the frustrations of the experienced fighters who resented Viracocha’s retreat.

Next, he reinforced the city’s defenses and sent out scouts to gather vital intelligence on the Chanca troop movements.

These decisions seemed to have rapidly earned him the loyalty of a number of seasoned generals.

When the Chanca army finally reached Cusco, Pachacuti used the information gathered by his scouts to try and exploit the attacker’s overconfidence.

In particular, he positioned his soldiers in a defensive formation and drew the enemy into a series of costly engagements.

According to Inca accounts, his forces repelled each attack with such exceptional ferocity, that it was believed that the gods themselves had intervened to assist him.

Some traditions claim that stone warriors, brought to life with supernatural energy, rose up and fought alongside the Inca warriors.

After suffering one final, bloody defeat, the Chanca fled back to their homelands. After the battle, Pachacuti took the throne from both his father and brother.

He officially exiled his father for cowardice, and Inca Urco met his end at the hands of Pachacuti’s supporters.

This began a period where the new Inca ruler consolidated his authority by eliminating other rival claimants and forming new alliances with nearby regional leaders.

Expansion of the Inca Empire

Beginning in the 1430s, Pachacuti then launched military campaigns that aimed to subjugat neighboring polities to ensure that the Inca would never again face an exestential threat to their existence.

The same skills that helped him to defeat the Chanca were now used on a larger scale for his wars of expansion.

Firstly, he used reconnaissance to assess enemy strengths and weaknesses, and, once an army was assembled, Pachacuti deployed sent them to assault targeted weaknesses in key defensive positions.

The Lupaca and Colla, powerful groups in the Altiplano, faced his armies first.

Their strongholds fell quickly under sustained Inca offensives and their leaders were forced to recognize his authority.

However, rather than dismantling local power structures, Pachacuti installed Inca administrators alongside existing rulers as a way of guaranteeing stability while reinforcing his royal control.

To the north, the Chachapoya lived in quite mountainous terrain, which made direct assaults difficult and costly.

So, Pachacuti engaged in a prolonged campaign that gradually encouraged his enemy’s allies to consider strategic alliances with the Inca.

When possible, Inca commanders would divide enemy forces by sowing discord among rival factions.

As a result, some Chachapoya leaders defected to the Incas. Once sufficiently weakened, the Inca quickly conquered the last remaining strongholds.

Meanwhile, in the south, his forces advanced toward the Titicaca Basin, where they encountered the formidable Sillustani fortress but, we are told, the Inca engineers devised a number of effective siege tactics that overwhelmed its defenses.

As such the Inca were able to secure control over the region’s highly prized agricultural resources.

By the time these campaigns ended, Inca rule stretched across vast territories, with different traditions and geographical challenges.

As a result, Pachacuti needed to find a way to incorporate them into a single empire.

What is more, Pachacuti did not tolerate any challenges to his authority. Disloyal leaders faced swift retribution, and rebellious populations were relocated to weaken resistance.

By the end of his reign, he had transformed Cusco from a city-state into the center of a vast empire that ruled over millions from the mountains to the coast.

The political genius of Pachacuti

So, Pachacuti implemented a range of administrative reforms that divided his kingdom into four administrative regions, which was known as Tahuantinsuyu, meaning ‘the four suyu’ in Quechua.

These regions were known as Chinchaysuyu, Antisuyu, Collasuyu, and Cuntisuyu.

Each suyu had its own governor, who was responsible for collecting tribute and keeping order in their assigned districts.

Each province contained a hierarchy of officials, from local curacas to higher-ranking administrators who reported directly to the Inca.

This structure allowed orders to travel quickly and prevented individual leaders from amassing too much power.

Imperial inspectors, known as tokoyrikoq, or ‘those who see all’, monitored provincial rulers and to ensure their loyalty.

Next, he implemented the so-called mit’a labor system, which required subject populations to contribute manpower for any major construction projects in their region, or require them to undertake military service.

Each region also saw the construction of massive storehouses, known as qullqas, which were established along military roads in order to supply armies when they were on distant campaigns.

Likewise, garrisons were positioned in newly conquered regions, preventing rebellion and maintaining social order.

As a result, Pachacuti was confident that the empire could sustain large-scale projects without relying on permanent taxation.

Every able-bodied man provided labor for a set number of days each year, which meant that the state could maintain roads, construct fortresses, and expand agricultural terraces without disrupting local economies.

In return, workers received protection and access to state granaries during times of famine.

The architect of the Inca world

The newfound wealth created by his conquests allowed Pachacuti to create some of the most impressive engineering feats in Inca history.

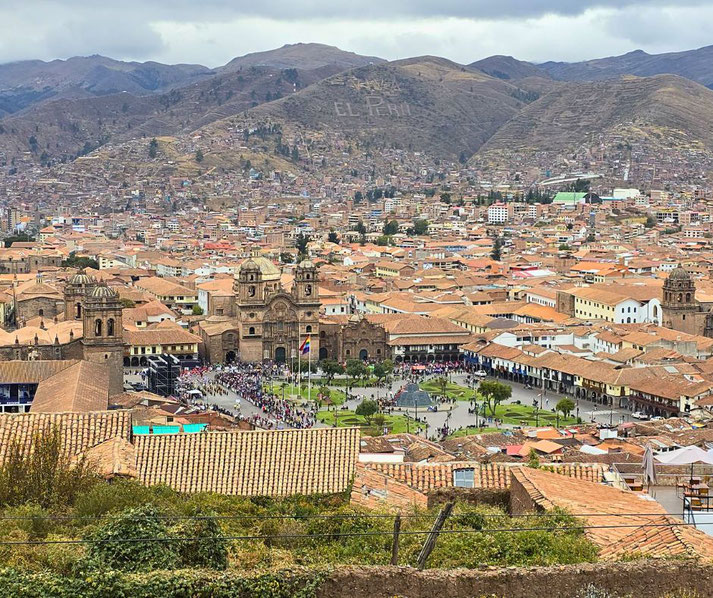

For example, he established the Qorikancha, an impressive temple dedicated to the sun god Inti in Cusco.

Also in the city, he ordered the building of defensive walls, aqueducts for fresh water, and the monumental Sacsayhuamán fortress, located on a hill overlooking the city.

Its enormous stone walls demonstrated the remarkable strength of Inca engineering, as it allowed the structure to withstand earthquakes.

Perhaps his most famous project was the commissioning of Machu Picchu, the mysterious holy city built on a steep ridge between the peaks of Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu.

The site contained grand temples, vast plazas, and awe-inspiring agricultural terraces, which meant that it could sustain a permanent or seasonal population.

Its remote location, as it was surrounded by dense cloud forests, protected it from outside threats but also meant that little information survives about its original purpose.

Some historians argue that it functioned as a royal estate, where Pachacuti and his retinue could retreat from the responsibilities of Cusco.

Others suggest that it operated as a religious sanctuary, where priests conducted ceremonies in honor of Inti.

Regardless, the time and effort it must have taken to build meant that it was of great importance to Pachacuti.

Pachacuti was also responsible for the greatest expansion of the Inca road network, which connected the empire’s distant provinces to its centre in Cusco.

The system was known as the Qhapaq Ñan and stretched more than 40,000 kilometers.

The emperor’s engineers constructed two primary routes: the Coastal Road, which extended along the Pacific shoreline, and the Highland Road, which crossed the Andean peaks.

Smaller paths branched off these main arteries, which helped even the most remote communities remain integrated into the state’s administration.

When needed, even suspension bridges, built from woven ichu grass, were placed across deep canyons.

This provided a surprisingly stable crossing for armies, traders, and messengers.

Pachacuti’s later life

By the 1460s, Pachacuti’s focus shifted from rapid territorial expansion to consolidation.

In newly conquered regions, he ordered the construction of Inti temples, which were designed to integrate local religious beliefs with the state religion.

Additionally, he organized the annual Inti Raymi festival to honor the sun god. In his final years, Pachacuti began preparing for succession.

By the late 1460s, he gradually transferred responsibilities to his son, Túpac Inca Yupanqui, who was an experienced military leader.

Túpac Inca had already commanded successful campaigns against the Chimú, which was the most powerful coastal civilization before its annexation into the empire.

Pachacuti observed these conquests closely, which allowed him to assess his son’s capabilities as a future ruler.

To prepare for a smooth transition, he instructed his officials to recognize Túpac Inca as his heir while he focused on finalizing construction of new palaces and ceremonial plazas throughout Cusco.

By 1471, Pachacuti officially withdrew from public life and allowed Túpac Inca to assume full control of the empire.

As a result, he spent his final years overseeing the completion of his panaka, which was a royal estate designed to house his descendants.

According to Inca tradition, his body was embalmed and placed in Cusco, where it remained an object of veneration for generations.

His mummified remains were even taken out and paraded during important ceremonies.

Ultimately, Pachacuti’s reign laid the groundwork for the sustained success of the Inca Empire, ensuring a stable foundation for future rulers.

As a result, Pachacuti’s successors inherited a unified and highly organized state, which was capable of sustaining and expanding the empire.

For example, Túpac Inca was easily able to expand the Inca Empire even further by focusing particularly on the northern and southern regions of the Andes.

His military campaigns followed the same successful strategies established by Pachacuti.

As such, Pachacuti’s long-term impact on Andean civilization remained significant, even long after his death.

By the time the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century, the Inca Empire had grown into a powerful and well-organized state, with a highly sophisticated infrastructure and a structured labor system.

The vast network of roads and trade routes continued to facilitate communication and movement of goods long after the empire’s collapse.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.