The pope as a prince: The political power of the Papal States

The Papal States, a unique blend of spiritual sanctity and temporal power, have long stood as a testament to the relationship between church and state in the heart of Europe.

From their inception in the turbulent Middle Ages to their eventual dissolution in the face of burgeoning nationalism, these territories have witnessed periods of grandeur, conflict, and transformation.

But how did the Papal States rise to prominence amidst the political complexities of medieval Europe?

What challenges did they face during the Renaissance, and how did they navigate the tumultuous waters of the modern era?

And how did the Lateran Treaty pave the way for the birth of the world's smallest sovereign state, Vatican City?

How the Papal States were formed

The origins of the Papal States are deeply intertwined with the broader context of European geopolitics and the ever-evolving relationship between the Church and secular powers.

In the early Middle Ages, the Italian Peninsula was a mosaic of territories, often at odds with one another, and the city of Rome was no exception.

The Lombards, a Germanic people who had established a kingdom in Italy, posed a significant threat to the Pope and the inhabitants of Rome.

Their incursions and territorial ambitions in central Italy under King Aistulf left the papacy in a precarious position, seeking allies to counter this looming menace.

Enter the Franks, a rising power in Western Europe. Their king, Pepin the Short, was approached by Pope Stephen II, who sought military assistance against the Lombards.

Recognizing the spiritual and political benefits of such an alliance, Pepin responded by launching a series of campaigns against the Lombards.

These military endeavors culminated in the Donation of Pepin in 756, a landmark event in which the Frankish king ceded a vast tract of land, previously held by the Lombards, to the Pope.

This territory, stretching across central Italy, formed the nucleus of what would eventually become the Papal States.

It was a gesture that not only solidified the alliance between the Franks and the papacy but also established the Pope as a temporal ruler in his own right.

The pope's dependence on the Holy Roman Empire

From the outset, the very foundation of the Papal States was inextricably linked to the Frankish realm, the precursor to the Holy Roman Empire.

The crowning of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800 AD was emblematic of this bond.

By bestowing upon Charlemagne the title of Holy Roman Emperor, the papacy was not only recognizing the Frankish king's dominance over Western Christendom but also ensuring a powerful protector for the nascent Papal States.

However, as the decades rolled into centuries, the dynamics between these two colossal entities began to shift.

The Holy Roman Empire, with its vast territories and diverse populace, often found its interests at odds with those of the Papal States.

One of the most significant flashpoints in this relationship was the Investiture Controversy of the 11th and 12th centuries.

At its core, this was a dispute over who held the authority to appoint bishops and other high-ranking church officials within the empire: the Pope or the Emperor.

This struggle was not merely about ecclesiastical appointments but represented a broader contestation of power and influence between secular and religious authorities.

The eventual resolution, the Concordat of Worms in 1122, was a compromise, delineating the roles of both the Emperor and the Pope in such appointments, but it also underscored the delicate balance of power that existed between the two.

The pope as a territorial conqueror

The very nature of the Papal States, straddling the spiritual and temporal realms, meant that territorial expansion was both a matter of divine mandate and geopolitical necessity.

As the Middle Ages progressed, successive popes sought to consolidate and expand their territories, ensuring that the Papal States remained a formidable power in the Italian Peninsula.

One of the primary drivers behind this territorial expansion was the need for security.

Surrounded by powerful and often hostile neighbors, the Papal States were in a constant state of vigilance.

To the north, the Holy Roman Empire, with its shifting allegiances and territorial ambitions, posed a perennial challenge.

To the south, the Kingdom of Sicily and later the Kingdom of Naples, with their own designs on the Italian Peninsula, were frequent adversaries.

In this volatile landscape, the papacy often found itself forging alliances, sometimes with unlikely partners, to safeguard its territories.

The use of papal legates, emissaries endowed with both diplomatic and military powers, became a common strategy to negotiate, and when necessary, defend papal interests.

However, the Papal States were not merely passive players in this game of territorial chess.

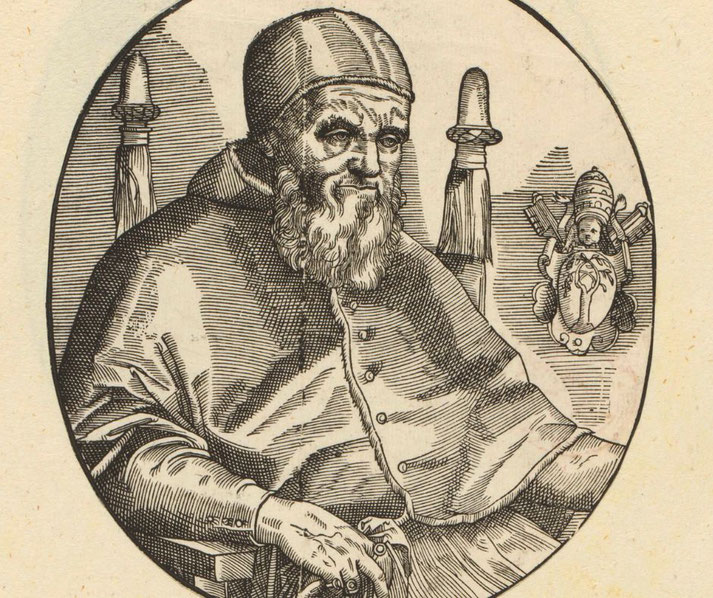

Under the leadership of assertive popes, most notably the likes of Pope Julius II in the early 16th century, known as the 'Warrior Pope', the Papal States embarked on military campaigns to reclaim lost territories and annex new ones.

These endeavors were not without their challenges. The very act of a spiritual leader waging war often drew criticism, both from within the Church and outside.

Yet, for the popes, the preservation and expansion of the Papal States were seen as essential to maintaining the Church's independence and authority.

The Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism

The Avignon Papacy and the subsequent Western Schism stand as two of the most tumultuous periods in the history of the Catholic Church, casting long shadows over both its spiritual authority and the temporal integrity of the Papal States.

The 14th century, marked by political intrigue, religious dissent, and societal upheaval, set the stage for these unprecedented events.

The Avignon Papacy, often referred to as the 'Babylonian Captivity' of the Church, began in 1309 when Pope Clement V, under the influence of the French King Philip IV, decided to relocate the papal residence from Rome to Avignon, a city in southern France.

This relocation was initially seen as a temporary measure, driven by the unstable political climate in Rome and the broader Papal States.

However, what was meant to be a brief sojourn turned into a stay of nearly seven decades, with seven successive popes, all of French origin, reigning from Avignon.

This extended absence from Rome had profound implications. The Papal States, without the direct presence of the pope, faced internal strife and external threats, while the city of Rome itself fell into decline.

Moreover, the close proximity of the papacy to the French crown raised questions about the independence and impartiality of the Church, with many fearing undue French influence on religious matters.

The return of the papacy to Rome in 1377, under Pope Gregory XI, should have marked the end of this challenging chapter.

However, it was merely the prelude to an even greater crisis: the Western Schism. Following Gregory's death, the subsequent election of Pope Urban VI in Rome and the later election of an antipope, Clement VII, in Avignon, plunged the Catholic world into chaos.

Christendom was now faced with the unprecedented situation of multiple claimants to the papal throne, each with their own set of supporters among Europe's monarchs and principalities.

This schism, which lasted for 39 years, was not just a religious crisis but also a political and diplomatic quagmire.

The Papal States, already weakened by the Avignon exile, were further fragmented by shifting allegiances to the rival popes.

The resolution to this schism came with the Council of Constance (1414-1418), which sought to heal the rift by deposing the existing claimants and electing Pope Martin V as the sole legitimate pope.

While the Western Schism was formally ended, its repercussions were long-lasting.

The prestige and authority of the papacy had been severely tarnished, and the unity of Christendom was fractured.

How the Renaissance revolutionised the Papal States

The Renaissance, a period of profound cultural, artistic, and intellectual rebirth between the 15th and 17th centuries, had its epicenter in the Italian Peninsula.

As cities like Florence, Venice, and Milan burgeoned into hubs of innovation and creativity, the Papal States, with Rome at its heart, were not mere spectators but active participants in this grand revival.

In the wake of the tumultuous Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism, the papacy was keen on reasserting its spiritual and temporal authority.

The Renaissance provided the perfect canvas for this endeavor. Popes of this era, recognizing the power of art and architecture as tools of propaganda and piety, became patrons of some of the most illustrious artists of the time.

With the backing of popes like Nicholas V, Julius II, and Leo X, Rome was transformed. The city, which had witnessed decline during the papacy's absence in Avignon, was rejuvenated with grand basilicas, palaces, and public spaces.

The construction of the monumental new St. Peter's Basilica, which started in 1506, symbolized the Church's aspirations to project its majesty and divine mandate.

Yet, the relationship between the Renaissance and the Papal States was not just limited to grand architectural endeavors.

The papal court became a magnet for artists, scholars, and thinkers. Figures like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Bramante found patronage and purpose in Rome, creating masterpieces that would become timeless testaments to the era's genius.

The Sistine Chapel's ceiling, the Raphael Rooms, and the design of St. Peter's Dome stand as enduring symbols of this symbiotic relationship between the papacy and the arts.

However, this golden age was not without its shadows. The very popes who championed the Renaissance were often embroiled in political intrigues and military campaigns to safeguard and expand the Papal States.

The Borgia and Medici popes, while great patrons of the arts, were also astute political players, navigating the complex power dynamics of the Italian city-states.

Furthermore, the lavish expenditures on art and architecture, coupled with the perceived moral laxity of the Renaissance papal court, sowed seeds of dissent.

This dissent would, in the subsequent century, find its voice in the Protestant Reformation, challenging the very foundations of the Church.

The Church in crisis

The trajectory of the Papal States, much like any great historical entity, was marked by periods of ascendancy and decline.

As Europe transitioned from the heights of the Renaissance into the modern era, the Papal States faced a myriad of challenges, both internal and external, that would test the very fabric of its existence.

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century was a watershed moment. Initiated by Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, this religious movement rapidly spread across northern Europe, challenging the doctrinal and institutional authority of the Catholic Church.

While the Papal States themselves remained staunchly Catholic, the broader religious fragmentation of Europe led to significant political and diplomatic consequences.

The Catholic Church's efforts to counter the Reformation, known as the Counter-Reformation, not only involved theological debates but also saw the mobilization of military resources, as religious divides often translated into geopolitical conflicts.

Amidst this backdrop of religious upheaval, the Papal States faced another devastating blow: the Sack of Rome in 1527.

Orchestrated by the mutinous troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, this event saw Rome subjected to pillage and devastation.

The Sack, beyond its immediate destruction, symbolized the waning temporal power of the papacy in the face of rising European nation-states.

The challenges for the Papal States did not abate as the centuries progressed. The Enlightenment era, with its emphasis on reason, science, and secularism, posed ideological challenges to the Church's authority.

Philosophers and thinkers began advocating for a separation of church and state, questioning the very premise of a religious entity like the Papal States wielding temporal power.

The fall of the Papal States

The 19th century witnessed a fervent wave of nationalism sweeping across Europe, reshaping political landscapes and redrawing boundaries.

Italy, a patchwork of city-states, kingdoms, and duchies, was no exception. The clarion call for a united Italy, 'Risorgimento' as it was termed, echoed across the peninsula, challenging the very existence of the Papal States and setting the stage for a dramatic confrontation between the ideals of nationhood and the millennia-old temporal power of the papacy.

The initial seeds of Italian unification were sown in the early 19th century, inspired by the revolutionary ideals of liberty and nationhood emanating from France.

Various secret societies and movements, such as the Carbonari, championed the cause of a unified Italy, free from foreign domination and internal fragmentation.

However, it was the concerted efforts of key figures like Giuseppe Mazzini, a visionary thinker; Count Camillo di Cavour, the astute Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia; and Giuseppe Garibaldi, a charismatic military leader, that gave tangible momentum to the unification movement.

By the 1860s, significant parts of the Italian Peninsula had been unified under the banner of the Kingdom of Sardinia, primarily through a combination of diplomacy, alliances, and military campaigns.

Yet, the Papal States remained a significant holdout. Protected by French troops and buoyed by the spiritual authority of the Pope, these territories presented a formidable challenge to the unifiers.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that any direct assault on the Papal States risked alienating Catholic populations and drawing the ire of Catholic-majority nations.

The turning point came in 1870. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War compelled Napoleon III to withdraw French troops from Rome, leaving the Papal States vulnerable.

Seizing this opportunity, the Kingdom of Italy launched a military campaign, culminating in the Capture of Rome on September 20, 1870.

Despite a token resistance, the city fell, and with it, the last vestiges of the Papal States were absorbed into the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Italy.

The Lateran Treaty and the birth of Vatican City

The dissolution of the Papal States in 1870 left an enduring question in its wake: What would be the status of the Pope and the tiny enclave of the Vatican within the newly unified Italy?

This 'Roman Question', as it came to be known, was not merely a territorial dispute but a profound dilemma that touched upon issues of sovereignty, national identity, and the millennia-old authority of the papacy.

For nearly six decades, this question remained unresolved, casting a shadow over the relationship between the Italian state and the Catholic Church.

The crux of the issue lay in the Pope's dual role as both a spiritual leader of the Catholic Church and a temporal ruler of the Papal States.

With the annexation of these territories by the Kingdom of Italy, the Pope's temporal sovereignty was ostensibly extinguished.

However, the popes, starting with Pius IX and his successors, refused to recognize the Italian state's legitimacy, considering themselves 'prisoners' within the Vatican walls.

This self-imposed isolation was a symbolic gesture, underscoring the papacy's protest against what it perceived as an unjust usurpation of its territories.

The situation began to shift in the early 20th century. Benito Mussolini, who rose to power in Italy in the 1920s, recognized the importance of resolving the Roman Question to consolidate his regime and gain broader acceptance.

Negotiations between Mussolini's government and the Holy See, represented by Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, culminated in the signing of the Lateran Treaty on February 11, 1929.

This historic accord achieved several key outcomes. Firstly, it recognized the Vatican City as an independent and sovereign city-state, separate from Italy, thereby restoring the Pope's temporal sovereignty within its confines.

In return, the papacy formally recognized the Kingdom of Italy and renounced any claim to the former territories of the Papal States.

Additionally, the treaty established Catholicism as Italy's state religion (which remained until 1984), guaranteed the Church's role in religious education in Italian schools, and granted the Church certain financial compensations for its lost territories.

The Lateran Treaty, beyond its immediate provisions, had profound symbolic significance.

It marked a reconciliation between the Italian state and the Catholic Church, healing a wound that had festered for nearly six decades.

The birth of Vatican City, the world's smallest independent state, ensured that the Pope could exercise his spiritual duties without interference while acknowledging the realities of the modern nation-state system.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.