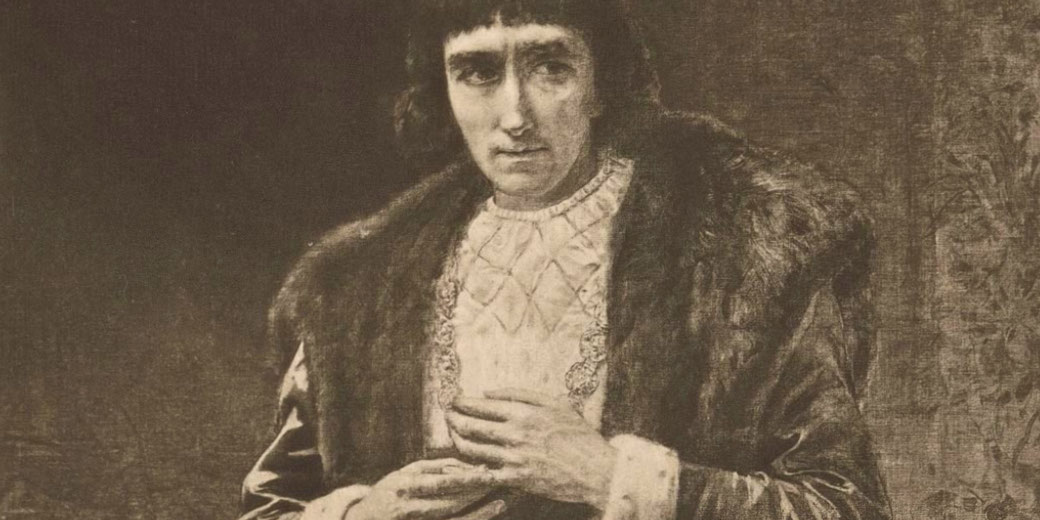

Richard III: Ruthless tyrant or victim of history?

Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England, remains one of the most polarizing figures in British history. Ascending to the throne in a time of civil strife known as the Wars of the Roses, he ruled for a brief but tumultuous two years, from 1483 until his defeat and death at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

His reign, while short-lived, was fraught with drama, political intrigue, and allegations of tyranny. Yet, beyond the monarch we often encounter in historical texts and Shakespearean drama, lies a figure shrouded in layers of myth and conjecture.

The very name "Richard III" evokes images of a hunchbacked villain, a usurper, and the supposed murderer of his young nephews, commonly referred to as the "Princes in the Tower."

However, modern scholarship often questions this narrative, presenting a more complex portrait of a king who was also a legal reformer, a brave soldier, and by some accounts, a victim of Tudor propaganda.

Richard's childhood and upbringing

Born on October 2, 1452, in Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, Richard was the youngest of three sons born to Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville.

His birth came at a time when England was on the brink of a devastating civil conflict known as the Wars of the Roses—a series of battles fought for control of the English throne between the Houses of York and Lancaster.

Richard's early life was shaped by this tumultuous backdrop, as his family was deeply enmeshed in the Yorkist cause.

In his childhood, he witnessed his father and elder brother, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, lose their lives in the struggle against the Lancastrian faction.

The young Richard was subsequently sent to the Netherlands for his safety, along with his older brother George.

As he grew older, Richard, like his brothers, was drawn into the familial quest to secure the throne for the House of York.

His eldest brother, Edward, eventually became King Edward IV in 1461, signaling a momentous Yorkist victory.

Richard was still a young teenager at this time, but he demonstrated considerable martial skill and a fierce loyalty to his family.

He was knighted at a young age and given significant responsibilities, including governance of the North of England.

Despite his youth, he proved himself an able administrator and military commander, earning the respect and allegiance of the northern nobles.

His closeness to Edward IV helped solidify his place in the political landscape, but it was his own competence that truly distinguished him.

As a young adult, Richard married Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, thereby linking himself to another powerful family in the Yorkist fold.

The union was not just a political alliance; by many accounts, it was a loving marriage, a rarity in the high-stakes matchmaking of medieval nobility.

Richard and Anne had one son, Edward, although the child would not live past his adolescence, leaving Richard without a direct heir—a circumstance that would complicate the already fraught issue of royal succession.

The dramatic way that Richard seized the throne

When Edward IV died unexpectedly in April 1483, the landscape of English politics was thrown into immediate disarray.

Richard, then Duke of Gloucester, found himself at a critical juncture. Edward IV's eldest son and Richard's nephew, also named Edward, was just a child of 12, and the realm braced itself for a potentially unstable minority reign.

Richard, known for his loyalty to his late brother, was initially named Lord Protector for young Edward V.

Yet, the situation quickly escalated into a power struggle between different factions within the Yorkist court, most notably involving the Woodville family, to whom young Edward's mother belonged.

Richard had long been wary of the Woodvilles, who had gained considerable influence during Edward IV's reign.

Within a few months of his brother's death, Richard made the stunning move to declare his nephews illegitimate, claiming that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville had been illegal due to a pre-existing contract the late king had with another woman.

This claim was solidified in the English law by an act of Parliament known as Titulus Regius.

As the boys were declared illegitimate, Richard, then the highest-ranking legitimate heir, was offered and accepted the crown, becoming Richard III.

The swift and calculating manner in which he seized the throne shocked many contemporaries and has been the subject of historical scrutiny ever since.

Had Richard been planning this coup all along, or was it a reactionary move prompted by the perceived threat of the Woodville faction?

What happened to the princes in the tower?

Perhaps one of the most enduring and haunting mysteries of English history revolves around the fate of the "Princes in the Tower," Edward V and his younger brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York.

The boys were placed in the Tower of London in the spring of 1483, following the death of their father, Edward IV.

Ostensibly, they were there in preparation for Edward V's impending coronation. However, as weeks turned into months, the princes were seen less and less, until eventually, they vanished entirely from the public eye.

The Tower, originally a royal residence, had increasingly become associated with imprisonment and death, and as the boys' visibility diminished, speculation about their fate reached a fever pitch.

No discussion of Richard III's reign can be complete without grappling with the enigma of the Princes in the Tower.

After Richard declared the boys illegitimate based on claims that their father's marriage was invalid, and subsequently took the throne, the princes became a liability.

While they remained alive, they would be a focal point for rebellion and a threat to Richard's rule.

Their sudden disappearance, therefore, cast a long, dark shadow over Richard's reign, leading many contemporaries and later historians to suspect that he had ordered their murder.

Despite extensive investigations, no concrete evidence has been found to confirm Richard's guilt or innocence.

Some theories even suggest that the boys may have been murdered on the orders of Henry Tudor, who would later become Henry VII, to solidify his own claim to the throne.

Richard III's reign

Richard III's reign, although lasting a mere two years from 1483 to 1485, remains one of the most intensely debated and scrutinized periods in English history.

Upon his accession, Richard faced a multitude of challenges, not least of which was the shadowy cloud of suspicion that hung over the fate of his nephews, the Princes in the Tower.

Yet, despite the adversity and the storm of controversy that surrounded him, Richard proved to be an able ruler in many respects.

He implemented legal reforms that made the judicial system more accessible to commoners, reflecting perhaps a pragmatic understanding of the importance of popular support.

One of his most notable contributions was the introduction of bail, designed to mitigate the harsh conditions of imprisonment before trial.

His reign also saw the advancement of printing, which would eventually lead to the broader dissemination of knowledge and the English language.

Nevertheless, Richard's political challenges were monumental. From the onset, his claim to the throne was met with resistance from various quarters.

The disappearance of his nephews lent urgency to the whispers of discontent, and various factions began to coalesce against him.

Among these was Henry Tudor, a distant relative of the Lancastrian line, who saw in Richard's vulnerability an opportunity to claim the throne.

While Richard made efforts to consolidate power and secure loyalty among the nobility, the undercurrent of opposition persisted, exacerbated by economic difficulties and the ever-present question of succession, given the death of his only legitimate son and heir, Edward, in 1484.

As the months passed, Richard found himself increasingly isolated, both politically and personally.

His wife, Anne Neville, died in March 1485, plunging him into grief and leaving the kingdom without a queen. It was a personal tragedy that also carried significant political repercussions, as it raised questions about the future of the Yorkist line.

Any hope of remarriage and producing an heir was complicated by the dark cloud of rumors and accusations that continued to hover over his rule.

Richard's reign was a ticking clock, and time was not on his side.

Finally, in August 1485, the proverbial sword hanging over Richard's reign fell. Henry Tudor, who had been living in exile in France, landed on the shores of Wales with a force of French and Scottish troops.

The Battle of Bosworth Field and Richard's death

The Battle of Bosworth Field, fought on August 22, 1485, marked not just the end of Richard III's brief but tumultuous reign, but also the conclusion of the Wars of the Roses, the long-running series of conflicts between the houses of York and Lancaster for control of the English throne.

Richard III, the last Yorkist king, faced off against Henry Tudor, a somewhat obscure claimant from the Lancastrian line whose maternal lineage gave him a tenuous claim to the throne.

Although Richard commanded a larger force and had the advantage of incumbency, the loyalties of key allies were uncertain, a reflection of the broader instability that had characterized his reign.

As the two armies met on the field, the tension was palpable. Richard's troops were better trained and equipped, but the morale was a different matter entirely.

Henry Tudor, on the other hand, had little military experience but was buoyed by the promise of change and the support of disaffected nobles, including the influential Stanley family.

The Stanleys' decision to intervene on Henry's side at a critical moment of the battle is often cited as a decisive factor in its outcome.

Richard, in a desperate bid to end the battle quickly, led a charge aimed at killing Henry Tudor. This daring move proved to be his undoing; Richard was cut down.

The death of Richard III on the battlefield led to the immediate proclamation of Henry Tudor as King Henry VII.

The new monarch's first act was to declare himself king by right of conquest, effectively backdating his reign to the day before the battle and ensuring that those who fought against him could be attainted as traitors.

Henry's victory at Bosworth was followed by his marriage to Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV, thereby uniting the warring houses and giving birth to the Tudor Rose as a symbol of this reconciliation.

This marriage, and the dynasty it inaugurated, represented a new chapter in English history, one that would include the reigns of such notable monarchs as Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

Why is Richard III still hotly debated today?

Few figures in English history have generated as much controversy and debate as Richard III.

For centuries, scholars, historians, and even playwrights like William Shakespeare have contributed to the formation of a highly polarized image of the last Yorkist king.

Shakespeare’s portrayal of Richard as a malevolent, deformed tyrant has had a lasting influence, shaping public opinion for generations and turning Richard into a caricature of villainy.

This dramatic representation, however, is far removed from the complexities of the historical figure, a man who was both a product and a victim of the turbulent times in which he lived.

One of the most contentious points of debate surrounding Richard III is his involvement in the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower.

The fate of his nephews, Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury, has been a subject of speculation for centuries, with theories ranging from murder at Richard's behest to escape and exile.

The lack of definitive evidence leaves room for multiple interpretations, each influenced by the historian's own perspective and often reflecting broader views on Richard's character and reign.

The issue has become so charged that it has divided scholars and enthusiasts into rival camps, sometimes referred to as "Ricardians" and "anti-Ricardians," each presenting arguments to exonerate or implicate Richard in this enduring mystery.

Another topic of heated discussion is Richard's usurpation of the throne. The legal maneuvers that declared his nephews illegitimate on the grounds of an allegedly bigamous marriage between their parents, Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, are seen by some as a necessary act to correct a line of succession tainted by illegitimacy.

Others view it as an unforgivable power grab, symptomatic of Richard's ruthless ambition.

The latter interpretation often aligns with broader criticisms of his character, including allegations of treachery against his brother, George, Duke of Clarence, who was executed for treason during Edward IV's reign.

Moreover, Richard III’s brief reign is often scrutinized for its administrative reforms and domestic policies.

Advocates point to his efforts to democratize the English legal system and the introduction of important legal innovations, such as the concept of bail, as evidence of enlightened governance.

Detractors argue that these initiatives were largely self-serving, designed to shore up faltering support rather than enact meaningful change.

Additionally, Richard's foreign policy, particularly his relations with France and Scotland, is a matter of ongoing investigation and debate, with interpretations often hinging on broader assessments of his strategic acumen and political integrity.

In recent years, the discovery of Richard III's remains has added a new dimension to these debates, inviting reconsideration of long-standing controversies.

The forensic evidence, which neither fully supports nor completely refutes the traditional accounts of Richard's physical deformities and manner of death, has fueled renewed interest and speculation.

This breakthrough has inspired a wave of both academic and popular reevaluations, extending the scope of debates to include ethical questions surrounding the reburial of historical figures and the role of modern science in shaping our understanding of the past.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.