The Silk Road: Ancient superhighway connecting Europe and Asia

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes that connected the East and West for centuries. It facilitated the interaction between many diverse cultures and empires over the centuries.

This vast network wasn't a single road but a series of pathways and trade routes that stretched over 4,000 miles, linking China with the Mediterranean Sea.

It connected the powerful Chinese, Roman, Persian, and later Byzantine and Ottoman empires, among others. This interaction led to the cities along the Silk Road becoming melting pots of culture and knowledge, where scholars and traders from different parts of the world could meet and exchange ideas.

When and why did the Silk Road begin?

The Silk Road began around the 2nd century BCE, following the efforts of the Han Dynasty in China to establish trade and diplomatic relations with Western countries.

This initiative, spearheaded by the Chinese emperor Wu, was driven by the desire to secure allies and trade goods, especially horses, that were crucial for the military.

The mission of Zhang Qian to the Western regions, which aimed to form alliances against the nomadic Xiongnu tribes, marked a significant starting point.

Although Zhang Qian's mission did not succeed in its immediate diplomatic goals, it opened the routes and information about the rich trading opportunities beyond China's borders.

How goods travelled between Europe and Asia

The Silk Road spanned thousands of miles, connecting the East with the West, and included several key locations critical to its function as a network of trade routes.

Starting from the ancient capital of Xi'an in China, the Silk Road branched out through the Gansu corridor and stretched across the deserts of Central Asia, including the Taklamakan Desert, known for its harsh conditions and the oasis cities that dotted its edges, such as Kashgar, Hotan, and Dunhuang. These cities served as vital rest and trade hubs for caravans.

From Central Asia, the routes extended further west, passing through cities like Samarkand and Bukhara in present-day Uzbekistan, which were central to trade and cultural exchanges due to their strategic locations and rich resources.

The road then forked towards the south through the Iranian Plateau, including cities like Tehran, and to the northwest through the Caucasus and Anatolia regions, reaching Byzantine Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey), which acted as a gateway between Asia and Europe.

Another branch moved southward from Central Asia into the Indian subcontinent, linking to ports on the coast of India, thereby connecting to maritime trade routes.

This intricate network of trade routes not only linked major empires and cities but also enabled remote regions to interact with the wider world, making places like Xi'an, Samarkand, Bukhara, and Constantinople key locations in the history of global trade and cultural exchange.

What items were sold and traded along the Silk Road?

The Silk Road facilitated the exchange of a wide variety of goods that were highly prized in different parts of the world, creating a global network of trade that was unprecedented in its scope and diversity.

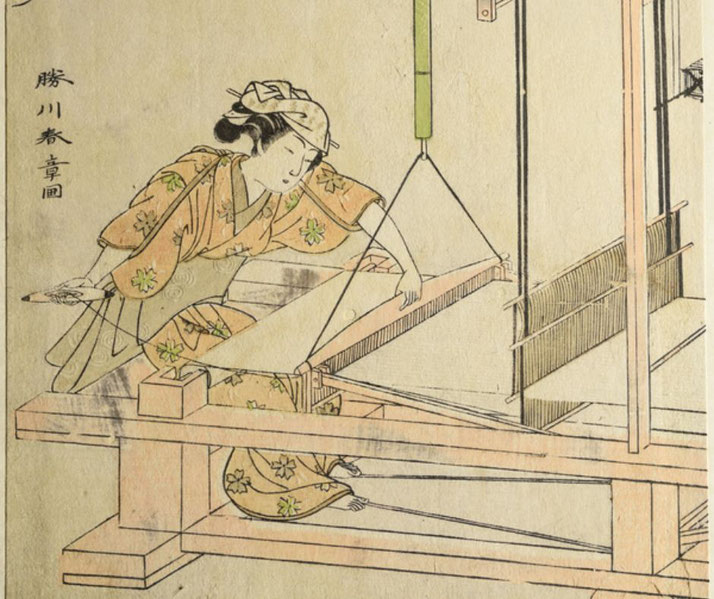

Silk, as the name of the route suggests, was one of the most sought-after commodities, originating from China and highly valued in Rome, Persia, and other parts of Europe for its beauty and luxury.

However, the trade was far from being limited to silk. Goods such as spices, including pepper, cloves, and cinnamon from India and Southeast Asia, were in high demand in Europe for their use in flavoring and preserving food.

Precious stones and metals also moved along these routes, with gold and silver from Europe traveling eastward, and jade, rubies, and lapis lazuli moving west from Asia.

Textiles, including fine woolen goods from Central Asia and cotton from India, were traded extensively, along with carpets, tapestries, and other artisanal crafts that represented the diverse artistic traditions of the Silk Road cultures.

In addition to these material goods, the Silk Road was instrumental in the exchange of knowledge, culture, and religion.

Technologies such as papermaking and gunpowder, as well as the practice of printing, spread from China to the West, significantly impacting European societies.

Religious beliefs and practices, including Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, were also disseminated along these routes, influencing spiritual and cultural landscapes across continents.

Agricultural products, including various grains and fruits, were traded locally and over long distances, introducing new food crops to distant lands.

Medicinal herbs and knowledge of their uses were exchanged between healers and scholars, contributing to the spread of medical knowledge.

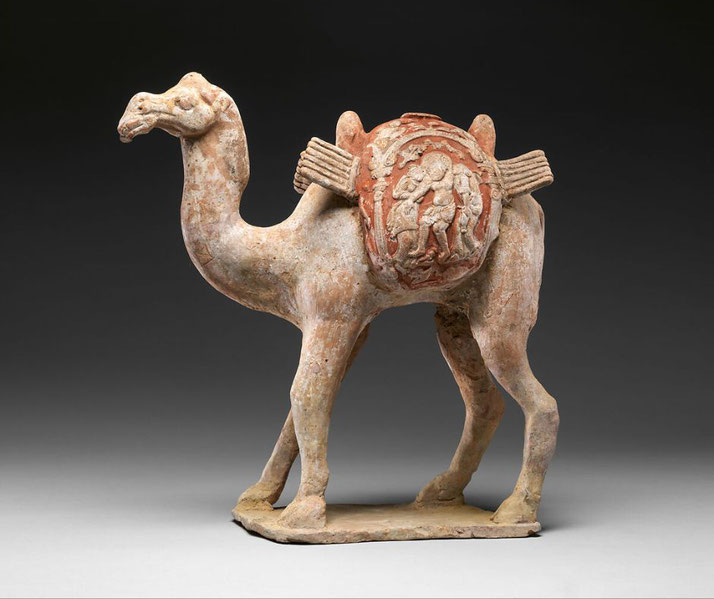

Horses, camels, and other livestock were highly valued both as transport animals and for their role in warfare and agriculture, moving primarily from the steppes of Central Asia to markets in China and the Middle East.

Why did the Silk Road disappear?

By the end of the 15th century, European explorers such as Vasco da Gama had discovered sea routes to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope, offering a faster, cheaper, and safer means of transporting goods than the overland Silk Road.

The spread of the Black Death in the 14th century also played a crucial role in diminishing the Silk Road's usage.

The pandemic, which traveled along the trade routes from Asia to Europe, resulted in the deaths of millions, disrupting trade and causing economic turmoil.

Furthermore, the Mongol Empire, which had provided a measure of stability and safety for traders on the Silk Road in the 13th and early 14th centuries, began to fragment after the mid-14th century.

This fragmentation led to increased risks for traders due to the lack of a unifying power that could ensure safe passage across the vast territories.

Finally, political changes in the regions surrounding the Silk Road further contributed to its decline.

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 and the subsequent control of the surrounding regions made the traditional land routes to the East more difficult and costly for European traders.

The Ottomans' monopolistic practices and taxes increased the costs for European merchants, which incentivized the search for alternative trade routes.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.