Why the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan was truly remarkable

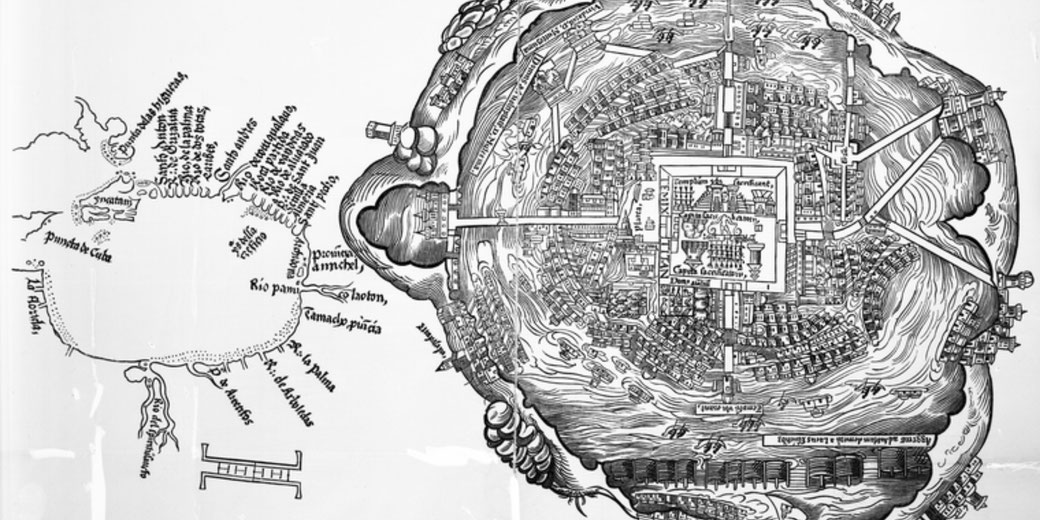

Surrounded by shimmering waters and crowned by towering temples, Tenochtitlan rose like an island dream in the centre of Lake Texcoco.

The city gleamed with vibrant colors, its plastered walls painted with bright murals and its markets alive with the clamor of trade.

Engineers shaped floating gardens that transformed the lake into fertile farmland, while broad causeways connected this watery wonderland to the surrounding shores.

At its center stood the imposing Templo Mayor, a monumental symbol of brutality and colonial power.

Why did the Aztecs build their city on a lake?

In the early 14th century, a group of Nahuatl-speaking people known as the Mexica began searching for a new home and they wandered through the central valley of Mexico.

They were motivated by the divine prophecy of their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli, who, according to a sacred vision, told them that they were to establish their city where they found an eagle perched on a cactus, clutching a snake in its talons.

By 1325, they reached the swampy shores of Lake Texcoco, where they finally witnessed this extraordinary sign and began the construction of their city, which they named Tenochtitlan.

By the early 16th century, Tenochtitlan had grown into a sprawling metropolis, covering an estimated five square miles and housing a population of approximately 200,000 people.

This made it one of the largest cities in the world at the time. Its scale required a highly organized infrastructure to sustain such a dense and diverse population.

The city’s layout, which was divided into calpulli districts, facilitated efficient administration and resource distribution.

Each district functioned as a self-contained unit, complete with residential areas, temples, and marketplaces.

These districts were carefully arranged around the central ceremonial precinct.

They provided structure and order to the sprawling metropolis.

To support this immense population, Tenochtitlan relied on a network of public amenities that ensured the city’s functionality.

Housing varied across social classes, with the nobility residing in large stone homes decorated with murals and mosaics, while commoners lived in adobe structures with thatched roofs.

Sanitation was maintained through an advanced waste removal system, which included public latrines and workers who transported waste out of the city to be used as fertilizer.

Fresh water, brought in through aqueducts from springs on the mainland, supplied homes, public fountains, and baths.

Ingenious solutions: How the Aztecs turned water into land

The Aztecs created chinampas, which were floating gardens that transformed the swampy environment of Lake Texcoco into a productive agricultural system.

These chinampas were rectangular plots constructed with layers of mud, lake sediment, and organic material, which were supported by wooden stakes and rooted in the shallow lakebed.

This design, which was both efficient and sustainable, provided fertile soil for crops such as maize, beans, and squash.

The canals separating the chinampas allowed for irrigation and easy access to the plots by canoe.

This meant that food production could flourish despite the challenging conditions and was critical to supporting the city’s growing population.

A network of canals facilitated efficient transportation and commerce. They crisscrossed the city like streets, which enabled the movement of goods and people in a highly organized manner.

Canoes were the primary mode of transportation, as they glide through the waterways to deliver agricultural produce, trade items, and building materials.

The canals also connected to the wider lake system, which meant that trade routes extended seamlessly beyond the city’s borders.

This dynamic waterway network allowed Tenochtitlan to function efficiently as both a residential hub and a thriving commercial center.

The integration of canals into the city’s design reflected an exceptional understanding of how to adapt urban planning to the challenges of its environment.

To connect Tenochtitlan to the mainland and ensure reliable transportation, the Aztecs also built sturdy causeways, which were raised stone roads extending across the lake.

They included removable wooden bridges, allowed for secure access during times of peace and could be retracted during invasions to protect the city.

The construction required immense labor and precise engineering to stabilize the roads on the water.

Additionally, these causeways helped trade and communication that meant that Tenochtitlan remained connected to the broader region.

Furthermore, the Aztecs implemented dikes and aqueducts to manage water levels and supply the city with clean drinking water.

In particular, the dike of Nezahualcoyotl, which was a monumental barrier constructed to separate fresh and brackish water, safeguarded the agricultural zones from contamination and regulated flooding.

Aqueducts, which were built with stone and wood, also carried fresh spring water from the mainland directly into the city.

A marketplace like no other: The bustling trade of Tlatelolco

One of the most important parts of the city was known as Tlatelolco. It was the marketplace and it thrived as a dynamic center of commerce that supported the economic needs of Tenochtitlan and the surrounding region.

This vast open space could accommodate up to 60,000 merchants and buyers daily according to historical records.

It was carefully organized into sections specializing in specific goods. Vendors offered items such as cacao, maize, obsidian tools, and brightly colored textiles. Luxury items included quetzal feathers and jade ornaments.

It functioned through the use of barter, with cacao beans often serving as a form of currency.

In addition, Aztec officials were stationed in the market, and they ensured order and fairness by regulating transactions and resolving disputes.

Tenochtitlan also played a significant role in regional and long-distance trade networks that connected the empire to distant territories.

Merchants known as pochteca were skilled intermediaries who traveling vast distances to acquire rare and valuable goods.

These traders brought back items such as tropical bird feathers, gold, turquoise, and exotic animals, which were prized within the capital.

Tenochtitlan’s central location within the lake system allowed it to serve as a hub where goods from across Mesoamerica converged.

Canoes transported items to the city’s docks, where they were unloaded and distributed through the markets.

This trade network, supported by the city’s advanced infrastructure, which ensured the flow of resources that sustained the empire’s population and enriched its ruling elite.

Why the Spanish were amazed by Tenochtitlan

When the Spanish first glimpsed Tenochtitlan in 1519, they were struck by its immense size and elaborate structure, which contrasted sharply with their expectations.

The city appeared to float on the water of Lake Texcoco and gave the city a striking resemblance to Venice.

The city’s enormous scale immediately impressed the Spanish, who later recorded their amazement in their personal accounts.

They noted the vibrant colors of the textiles, which were woven from cotton and often adorned with intricate patterns.

Golden jewelry and polished obsidian tools demonstrated the high level of craftsmanship among Aztec artisans.

The Spanish were equally intrigued by the presence of live animals for trade, including turkeys and small dogs bred for food.

As they entered the city, the Spanish marveled at its well-organized layout and the vibrant markets.

In particular, at the Tlatelolco marketplace, the Spanish noted the variety of goods available, from basic foodstuffs.

As they explored further, the Spanish were astonished by the exotic animals kept in the city’s royal menagerie.

This collection included jaguars, pumas, and colorful birds such as macaws and quetzals.

These animals, which were brought from distant regions, were housed in specially designed enclosures that mimicked their natural habitats.

The quetzal feathers, which were highly valued for their rarity and used in ceremonial headdresses, symbolized both wealth and power.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.