The brutal reality of Aztec warfare

The Aztec civilization is known for its impressive architecture, sophisticated social structure, and rich artistic traditions. However, one aspect of Aztec culture that is often overlooked is their military prowess.

War played an important role in Aztec society, and it was the primary way that they maintained control over their neighbours.

Their warfare was not only a means of gaining power and resources but was also deeply connected to their religious beliefs and rituals, involving human sacrifice and bloodshed on a massive scale.

The road to war

The Aztec culture went to war in a methodical fashion: they had a sequence of steps that they followed in order to justify conflict.

Firstly, before going to war, the Aztec emperor consulted with a group of people called the pochteca.

The pochteca were a powerful merchant class who made the majority of their wealth through trade between the Aztec Empire and the kingdoms on their borders.

As a result, they were often used to help gather intelligence on neighbouring city-states, such as the kind of valuable goods that could be found there, which they would then report back to the Aztec emperor.

The pochteca would also provide detailed reports on the military capabilities and alliance of their neighbours, allowing the Aztecs to make informed decisions about which enemies to engage in battle.

If the proposed land was deemed to be wealthy enough, and the likelihood of victory high enough, the emperor would then send an ambassador to the city.

The ambassador would deliver a message from the Aztec emperor and offer the ruler the chance to voluntarily join the Aztec Empire in return for regular monetary tribute, valuable goods, labor, or military support.

The potential target was then given 20 days to respond. If they didn't choose to join, the Aztec envoy threatened them with war.

If this didn't change their mind, the Aztec considered the fault to be with the foreign land and they declared war on them.

Sending an ambassador before declaring war was a common practice among many ancient civilizations, and it allowed for the possibility of a peaceful resolution to conflicts.

Military training

The Aztecs did not have a full-time, professional army of soldiers. Instead, every male in Aztec society was considered a potential warrior.

Therefore, they began military training from childhood. Young boys were educated in schools called telpochcalli, where regular physical exercise, marching drills and weapons practice formed key parts of their lessons.

Once they were adults, they participated in coordinated drills with other warriors so that they were prepared to fight in battle.

There were also rewards to being involved in war. Aztec men who excelled in bravery, or captured a significant number of enemies for sacrifice, received gifts and titles.

It was even possible for peasants to rise through the social classes if they were gifted soldiers.

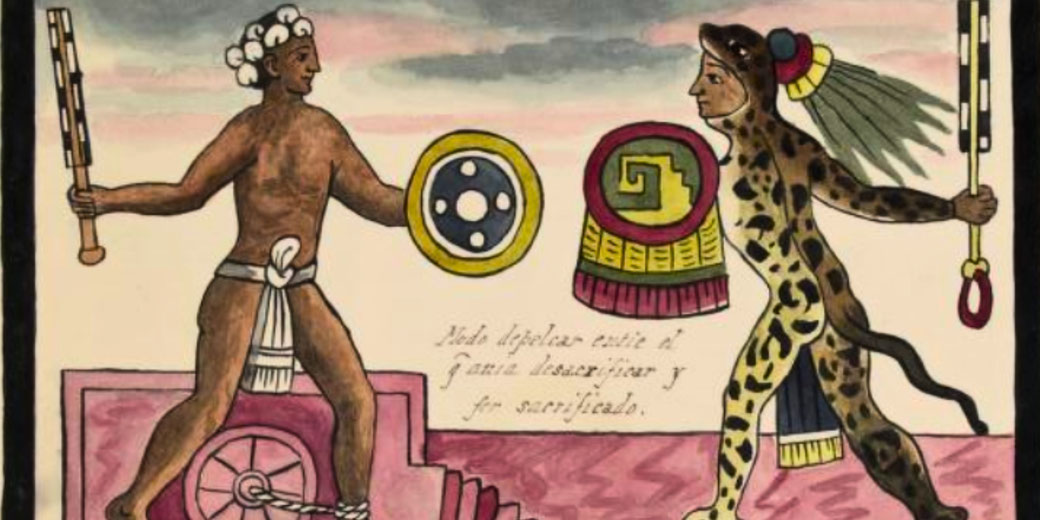

In preparation for battle, the warriors would perform a sacred dance with their weapons and armor.

This included head-dresses that represented ferocious animals like eagles, jaguars, serpents, and even coyotes.

Their shields also bore images of the same beasts and decorated with brightly colored feathers.

It was believed that by associating with the spirit of nature, the soldiers would gain some of their powers and secure an advantage over their enemies.

In battle

When the Aztecs finally met their enemies on the battlefield, they used prepared tactics to try and win the conflict.

As the armies approached each other, they would try and weaken their opponents by using atlatls (spear throwers), shooting arrows or throwing stones.

Once engaged, the Aztec would attack using macuahuitl, a wooden club edged with shards of razor-sharp obsidian.

The primary aim of battle was not to kill as many as possible, but instead, to capture as many enemies as they could to take back to Tenochtitlan to be sacrificed at their temples.

If the Aztec won the battle, they would march on the defeated city. Once there, they would destroy the main temple and then take some of the men, women and children, tie them together, and march them in them in long lines back to Tenochtitlan.

The Aztec would allow the city to survive, as long as the leaders swore allegiance to Tenochtitlan and agreed to pay regular taxes.

If an individual warrior excelled in a battle, he would receive recognitions and rewards for both himself and his family.

Any slaves and wealth he captured remain his, and if he wanted to, he was allowed to marry several wives.

Even a person born a commoner could be promoted to the level of a quauhpilli (an 'eagle lord') or enter into the nobility.

The Flower Wars

The Flower Wars (also known as the “Flowery Wars” or “War of Flowers”) were a unique type of ceremonial warfare.

These wars were not fought for territorial gain, but rather as a religious practice to satisfy the Aztec gods of war and the sun.

During a Flower War, the Aztecs would choose a neighbouring city-state to engage in battle with, often one with which they had a pre-existing alliance or a peaceful relationship.

The two sides would agree upon a time and place for battle, and the objective was not to kill or conquer the enemy, but to capture as many prisoners as possible.

The captured prisoners would then be marched back to their enemy’s cities, where they would be sacrificed to the gods.

The origin of the Flowers Wars is not precisely known. Some scholars believe that the practice may have emerged among the peoples of central Mexico before the rise of the Aztec Empire.

Others believe the wars were a way for the Aztecs to test the miliary capabilities of their warriors and to prepare them for more serious battles.

The more famous Aztec Flower Wars occurred from around 1450 reportedly in response to several years of severe drought.

A series of poor harvests led to starvation, and the Aztec believed the gods needed more human sacrifices to fix the problem.

It was decided that to gather enough victims for a necessary sacrifice, a war had to take place.

Tlaxcala, a nearby city, who had also suffered starvation, agreed to the war.

The Flower War was considered a success and the environmental conditions improved.

The practice became an important part of Aztec culture and religion, and it continued to be practiced until the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.