How was Medieval Japan Unified?

From 1467 to 1615, Japan experienced a long period of civil war called the Sengoku Jidai, which means 'The Warring States' period.

During this time, individual daimyo fought each other using large samurai armies in order to be named shogun (supreme military commander) by the Japanese emperor.

If a shogun was not powerful enough to fight off his rivals, it encouraged others to attempt to take control as well.

Three particularly successful daimyo managed to seize power during this time, with each one gradually controlling larger sections of the country.

These three were known as the 'unifiers of Japan' and are examined in more detail below:

Oda Nobunaga (AD 1534-1582)

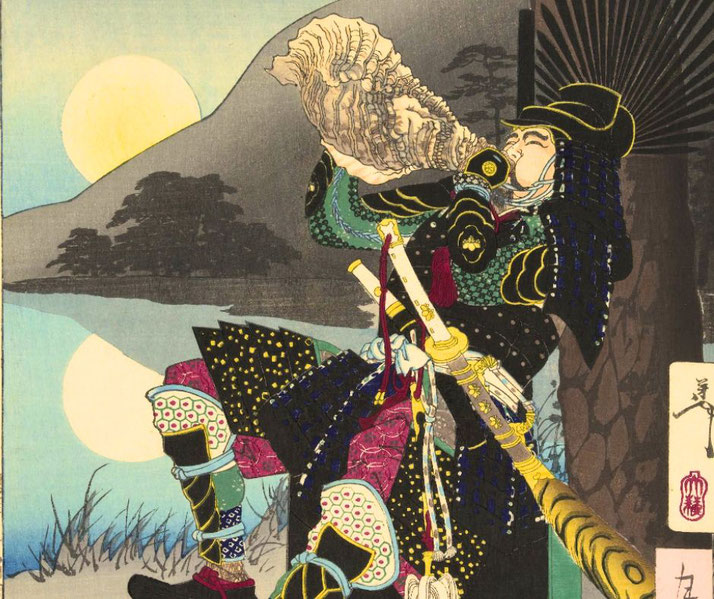

Oda Nobunaga came from Nagoya, in the region of Owari in Japan. Nobunaga had a reputation as a ruthless warlord who willingly experimented with new tactics to gain an advantage over his rivals.

Most famously, he adopted western gunpowder weapons which had appeared in the country following trading missions from the Portuguese in 1543.

Throughout his rise to power, Nobunaga struggled against the political power of some Buddhist monasteries that had their own 'warrior monks', who resisted him.

On some occasions, Nobunaga attacked these religious buildings and slaughtered the monks in them, which shocked the rest of Japan.

Nobunaga achieved his greatest success after winning the Battle of Nagashino in 1575, which led to the destruction of the once-powerful Takeda clan.

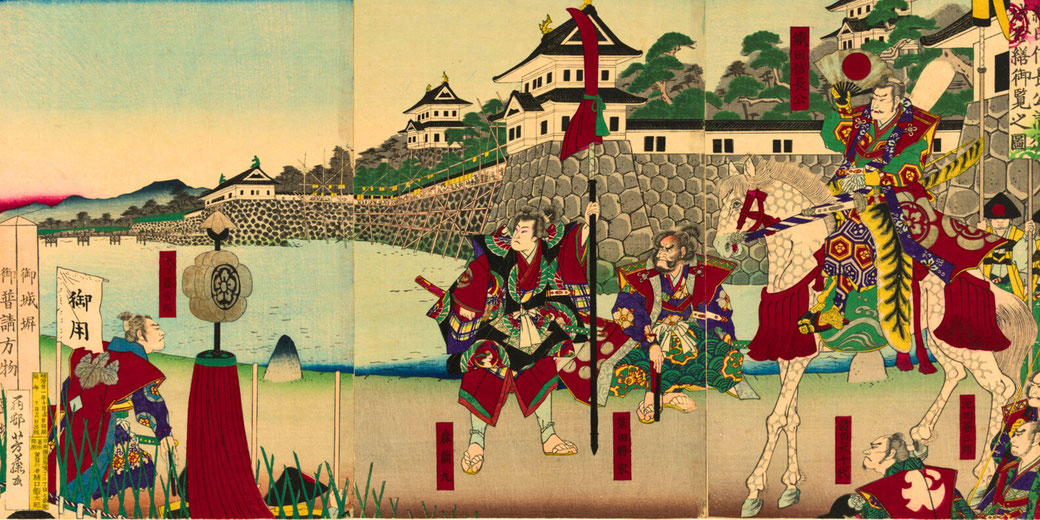

Subsequently, Nobunaga was able to seize control of the imperial city of Kyoto.

However, his brutal reputation led to his downfall, as one of his own military commanders, Akechi Mitsuhide, betrayed him, and Nobunaga was forced to commit suicide in a temple while his enemies burnt it down.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (AD 1536-1598)

The next 'unifier of Japan' arose after Oda Nobunaga and was named Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Hideyoshi actually served under Oda Nobunaga and had been promoted due to his gift for military matters.

By the time of Nobunaga's suicide, Hideyoshi was one of the most respected generals in his army.

Hideyoshi felt that it was his duty to avenge his former master's betrayal and death.

He launched a series of wars against his enemies and, by 1590, had become the most powerful daimyo in Japan.

Hideyoshi established his capital at Osaka and planned to expand Japanese power internationally by invading the Korean peninsula.

He launched two invasions, beginning in 1592, but by 1598, his forces had little success, and the conquest was abandoned upon his death in 1598.

Hideyoshi's most lasting impact on Japanese history is the enforcement of a strict class system that is akin to European feudalism.

He created laws that made it illegal for peasants to carry weapons and limited people from leaving their assigned social class.

Tokugawa Ieyasu (AD 1543-1616)

The greatest and final of the three unifiers was the daimyo of the Mikawa region: Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Ieyasu served as a general in Nobunaga's army and regularly achieved victories on the battlefield.

After Nobunaga's suicide, Ieyasu became a commander in Hideyoshi's forces as well.

When Hideyoshi died in 1598, Ieyasu became the protector of Hideyoshi's son, and he utilized his strong power base and support from various daimyo to rise to power.

Hideyoshi's other generals were angered by this move.

In 1600, Hideyoshi's former generals brought their combined armies against Ieyasu at the decisive Battle of Sekigahara.

This is one of the most famous battles in all of Japanese history, with over 200,000 soldiers involved.

However, Tokugawa Ieyasu used clever tactics to defeat his rivals, and his victory in the Battle of Sekigahara consolidated his rule and marked the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

The final resistance against Ieyasu was removed in 1615 with the fall of Osaka Castle.

Ieyasu established the Tokugawa Shogunate in Edo, which is the modern-day city of Tokyo.

This shogunate lasted from 1603 to 1868, enduring for more than 250 years.

The Tokugawa Shogunate

Successive Tokugawa shoguns created new laws to prevent any other daimyo from seizing power.

The daimyo were each assigned regions and government positions based on their loyalty.

Also, every daimyo had to pay for a private house in Edo, where members of their families were held as diplomatic hostages.

Every few years, all daimyo had to visit Edo, which was an expensive journey. In this way, the Tokugawa shogunate hoped to keep the daimyo poor enough that they would not rise in rebellion.

Ultimately, these strategies worked, and there was no significant rebellion against the Tokugawa until the middle of the 19th century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.