The miraculous Christmas Truce of 1914: When WWI soldiers on both sides (briefly) stopped war

The Christmas Truce of 1914 is one of the most remarkable and unexpected events in military history. For many people who hear about it, it restores our collective faith in humanity: even in the darkest times.

In the first year of World War I, a conflict that would eventually claim millions of lives, a spontaneous ceasefire took place in the frozen trenches of the Western Front.

On Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, soldiers from opposing armies, primarily the British and Germans, set aside their weapons and hostility to share a fleeting period of peace and goodwill.

What led to this remarkable, if temporary, call of peace?

And why did the war continue for another four horrific years?

Why the world was at war in 1914

World War I had started as a result of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary on June 28, 1914, in the city of Sarajevo.

This single tragedy set off a rapid chain reaction among the major European powers.

In the weeks following, a series of diplomatic and military maneuvers led to the escalation of tensions.

On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. It seems that they believed that the Serbian government had been involved in the plot to assassinate the Archduke.

Then, Russia, which was bound by treaty to Serbia, began to mobilize its forces.

Like falling dominoes, this lead Germany, an ally of Austria-Hungary, to declare war on Russia on August 1st.

Then, France, allied with Russia, found itself at war with Germany and, by extension, Austria-Hungary.

This conflict ultimately became global when Germany invaded Belgium on August 4th.

Belgium was an ally of the United Kingdom. So, Britain declared war on Germany in response to the violation of Belgian neutrality.

The first five months of the war saw a series of increasingly bloody battles. However, neither side was able to gain an upper hand.

Instead, by the end of 1914, the initial war of movement seen on the Western Front had given way to gruelling trench warfare, leading to a prolonged stalemate.

The war had become a costly struggle of attrition, with both sides constructing complex trench systems that extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border.

Why did the Christmas Truce happen?

By December 1914, soldiers on both sides were exhausted, demoralized, and bogged down in the muddy, frigid trenches.

In the face of the ongoing conflict, the festive season brought a sense of nostalgia and a longing for peace.

As Christmas Eve approached, a calm descended over parts of the Western Front. Both sides seemed to hope for a reprieve.

The strange event began with the Germans, who initiated the truce by decorating their trenches.

People from the time claimed that they adorned their positions with candles and small Christmas trees.

Across no-man's-land, the British and French troops observed these activities with curiosity and cautious optimism.

The atmosphere changed further as the German soldiers started singing Christmas carols.

It was at this moment, that disbelief was replaced by something more heart-felt.

Moved by the spirit of the moment, British and French soldiers chose to respond with their own carols.

In a strange moment, the two sides sung together: in different languages, but the same songs.

Men who were, just days prior, trying to kill each other, now shared in a rare moment of solidarity.

The remarkable events of Christmas Day 1914

The next day, Christmas Day itself, the spirit of goodwill took a more tangible form.

German soldiers, in a bold and perhaps foolhardy gesture, left their trenches and approached the Allied lines, calling out "Merry Christmas" in English.

Initially met with skepticism, the fear of a trap soon gave way to the realization that the Germans were unarmed.

Their intentions were peaceful.

The Allied soldiers reciprocated and also climbed out of their trenches.

As more soldiers joined, the no man's land, usually a place of immense danger, transformed into a common meeting ground.

The men exchanged gifts of cigarettes, food, and souvenirs. They showed each other pictures of their families and spoke about their homes.

They discovered commonalities despite their different languages and allegiances.

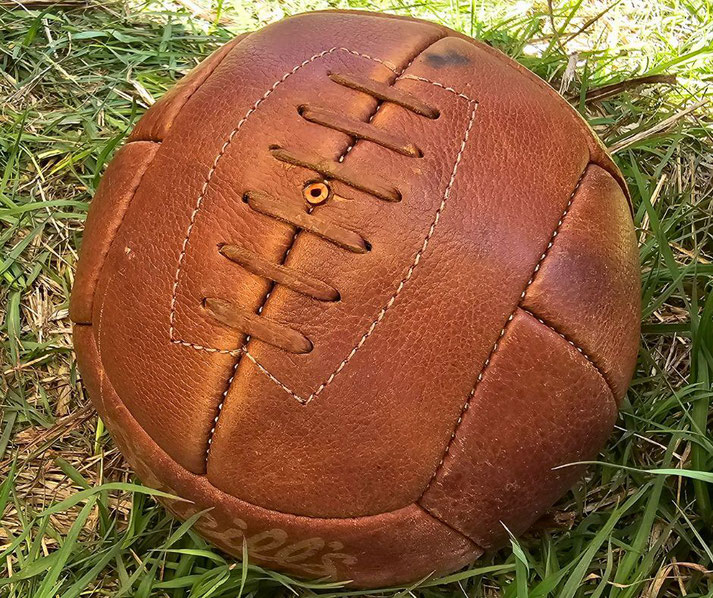

Accounts of the time mention that in various locations along the front, troops from both sides set up impromptu football games in no man's land.

These matches were played with makeshift balls, which were made from bundled cloth.

The games were friendly, and the scores mattered little; what was significant was the spirit of sportsmanship and the temporary sense of normality.

However, not all of the activities that day were about fun and festivities. Some soldiers used the cessation of hostilities to recover the bodies of their friends that still lay in no man's land.

Then, joint burial ceremonies were held, with troops from both sides paying their respects.

Why did the war continue despite the truce?

In many sectors, the truce came to an end on December 26th. Commanders on both sides, concerned about the fraternization weakening their troops' resolve to fight, ordered the resumption of hostilities.

In some instances, this order was met with resistance from the troops, who had developed a sense of camaraderie with their adversaries.

However, the strict discipline and structure of the military eventually compelled the soldiers to return to their roles as combatants.

The return to fighting often began with symbolic acts, such as firing shots in the air, to signal the end of the truce.

In some cases, soldiers shouted warnings to their erstwhile comrades in the opposing trenches, signalling to them that the fighting would recommence.

In other areas, the truce lasted a bit longer, extending into the first week of January 1915.

These extended truces were particularly prevalent in quieter sectors of the front, where the intensity of combat was lower.

Why was the Christmas Truce an important event?

The Christmas Truce is a curious moment. It does raise questions about the nature of obedience and discipline in the military context.

The fact that the truce was not officially sanctioned and occurred spontaneously across various parts of the front suggests a temporary breakdown of military discipline.

From a sociological perspective, the truce underscores the influence of cultural and traditional practices, such as Christmas celebrations, in fostering a temporary peace.

The shared cultural significance of Christmas for both the German and Allied soldiers enabled them to view each other through a lens of common cultural practices rather than as enemies.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.