The key thinkers of the Enlightenment and their revolutionary ideas

Curiosity about the natural world, human society, and the role of reason sparked a profound intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries.

This period witnessed thinkers across Europe and the Americas developing ideas that challenged tradition and promoted progress.

Through discussions on philosophy, politics, science, and even economics, they sought to encourage individuals to question authority and rely on reason as a guide to knowledge.

During this time, key figures emerged who proposed influential concepts that redefined government, rights, and freedom.

From John Locke’s natural rights to Rousseau’s advocacy for the general will, their ideas set a course that influenced revolutions and modern democracies.

What was the Enlightenment?

During the late 17th and 18th centuries, a vibrant intellectual movement swept across Europe, known as the Enlightenment.

It emerged during a period of scientific discovery, political upheaval, and philosophical inquiry.

In the wake of earlier events like the Scientific Revolution and the Reformation, thinkers began to advocate for reason and empirical evidence as the primary means of understanding nature and society.

This movement challenged longstanding traditions and established authority, leading to debates that redefined key concepts such as government, human rights, and personal freedom.

At the heart of the Enlightenment was a belief in the transformative power of knowledge.

Thinkers like Isaac Newton and René Descartes laid the groundwork for this shift by demonstrating that observation and logic could unravel nature's mysteries.

Their work inspired philosophers to apply similar methods to broader questions about humanity.

During this period, intellectuals met in salons and coffeehouses in cities like Paris, London, and Amsterdam, where cultural exchange flourished in a relatively open environment.

By the mid-18th century, Enlightenment ideas had reached a remarkable level of influence.

Writers and philosophers such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau produced works that criticized absolutist monarchies and proposed alternative political systems grounded in liberty and equality.

As a result, their arguments resonated deeply with readers in Europe and the Americas.

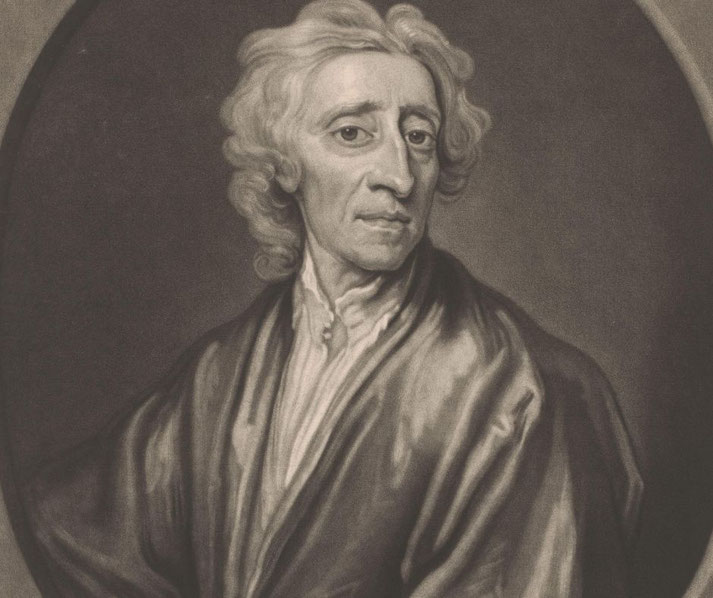

John Locke and the fight for natural rights

During the 17th century, John Locke, who was an influential English philosopher, articulated ideas that became foundational to modern political thought.

In his writings, particularly Two Treatises of Government (1689), Locke argued that all individuals possessed natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

He asserted that these rights were inherent and could not be taken away without due cause.

By grounding his arguments in reason and observation, Locke challenged the traditional belief in divine right monarchy, presenting a rational alternative that prioritized individual freedom and dignity.

Through his concept of the social contract, Locke explained the purpose of government as a mechanism to protect these rights.

He proposed that legitimate authority originated from the consent of the people it governed, not from hereditary privilege or divine ordination.

Governments, according to Locke, existed to safeguard the welfare of their citizens, who retained the right to withdraw consent if rulers became oppressive.

His logical framework directly opposed absolutist rule and provided a blueprint for establishing systems that prioritized accountability and representation.

Locke’s practical influence inspired revolutionary movements in both Europe and the Americas.

His writings deeply influenced figures like Thomas Jefferson, who incorporated Locke’s principles into the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Later, Locke’s emphasis on liberty and equality resonated with leaders of the French Revolution, who were seeking to dismantle an oppressive monarchy.

Voltaire: Should we dare to speak freely?

During the Enlightenment, Voltaire, who was a prolific French writer and philosopher, became a fierce advocate for freedom of speech and religious tolerance.

Through his essays, letters, and plays, he criticized the power of organized religion, particularly the Catholic Church, which he accused of fostering ignorance and intolerance.

His use of sharp wit and satire highlighted the abuses of authority by religious institutions and called for a more rational and humane approach to spiritual matters.

Voltaire believed in deism, which meant that he saw God as a creator who did not interfere with human affairs, rejecting the dogmas of established faiths.

As a result of his relentless critique of absolutism, Voltaire defended individual liberty as essential to a just society.

He openly condemned the arbitrary rule of kings who suppressed dissent and maintained rigid hierarchies.

In works such as Candide (1759), he exposed the hypocrisy and cruelty of those in power.

By advocating for reason, Voltaire sought to empower individuals to think independently, which was a bold position in a period where censorship and persecution were common tools of control.

Voltaire’s influence on European political thought was extensive, particularly through his correspondence with leaders like Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia.

His ideas inspired reforms aimed at reducing the power of the Church and promoting education.

Philosophers and revolutionaries drew heavily from Voltaire’s writings to support broader movements for civil rights and justice.

Why did Montesquieu believe power must be divided?

In 1748, Montesquieu published The Spirit of the Laws, which was an extensive analysis of political systems and their underlying principles.

In this work, he introduced the concept of separation of powers, which divided authority among legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

Montesquieu argued that this structure prevented any single branch from becoming overly powerful.

By establishing a system of checks and balances, where each branch could limit the others, he believed that individual freedoms could be better protected.

His detailed exploration of various governments, including ancient Rome and England, provided practical examples that reinforced his arguments.

In addition, Montesquieu profoundly influenced the development of modern democratic systems, particularly in the United States.

The framers of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 adopted his principles to design a government with distinct branches that would operate independently.

This structure created a framework where Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court each held separate responsibilities while maintaining the ability to check abuses of power by the others.

By incorporating Montesquieu’s theories, the Constitution ensured that no single institution could dominate the political process.

His emphasis on balancing power between institutions became foundational to democratic practices around the world.

Montesquieu’s work also influenced debates in Europe, particularly in France, where his critiques of absolutism inspired calls for reform.

His advocacy for rational and fair systems of governance resonated with those seeking to limit the authority of monarchs and promote broader participation in political decision-making.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the idea of the social contract

Jean-Jacques Rousseau published The Social Contract, which presented a radical vision of political organization grounded in the principles of popular sovereignty and the general will.

He argued that legitimate authority arose from the collective agreement of all citizens, who formed a social contract to govern themselves.

According to Rousseau, the general will, which represented the common interests of the people, should guide laws and policies.

In his vision, direct democracy was essential because it allowed citizens to participate actively in shaping the laws that governed their lives.

This concept challenged hierarchical systems and introduced an egalitarian approach to governance.

Rousseau also critiqued social inequality and highlighted the moral and societal impacts of wealth disparities.

In Émile, published in 1762, he outlined his views on education, proposing that children should learn through experience and develop their natural instincts before being introduced to formal instruction.

He believed that unequal access to education perpetuated societal divisions and argued for a system that cultivated virtue and independence.

This innovative approach placed importance on nurturing individual potential as a way to create a more just and balanced society.

Rousseau’s ideas profoundly influenced revolutionary thought, particularly during the French Revolution.

Leaders such as Maximilien Robespierre cited his work to justify their vision of a republic based in equality and the general will.

His critiques of privilege and advocacy for collective decision-making inspired broader movements seeking to dismantle feudal systems and establish democratic institutions.

Immanuel Kant: The role of reason

In 1784, Immanuel Kant published his influential essay What Is Enlightenment?, which addressed the intellectual foundations of the Enlightenment and the role of reason in human progress.

He defined enlightenment as humanity’s emergence from self-imposed immaturity, caused by a lack of courage to use one’s intellect without guidance from others.

Kant urged individuals to think independently and critically, emphasizing that freedom of thought was essential for intellectual growth.

His argument placed reason at the center of human advancement.

Throughout his philosophical writings, Kant developed a theory of moral autonomy and the categorical imperative, which was central to his ethical philosophy.

He argued that moral actions were not guided by personal desires but by universal principles that could be applied consistently by all rational beings.

According to Kant, individuals must act in ways that could be universalized without contradiction.

This framework established an objective basis for morality, which was independent of cultural or personal bias.

His emphasis on the capacity of individuals to determine moral principles through reason had profound implications for Enlightenment ideals, as it reinforced the importance of rationality and responsibility in ethical decision-making.

Kant’s insistence on reason as a tool for human liberation resonated with contemporaries seeking to challenge existing power structures.

Furthermore, his work became a foundation for later philosophical developments, particularly in German idealism and modern ethical theory.

As a result, Kant’s writings helped to deepen the intellectual framework of the Enlightenment, encouraging debates about human potential and the responsibilities of rational beings in a rapidly changing world.

Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ and the birth of modern economics

Adam Smith’s published work known as The Wealth of Nations was a groundbreaking work that laid the foundation for modern economics.

In this book, he introduced the concept of the ‘invisible hand’, which explained how individuals pursuing their self-interest could benefit society as a whole.

Smith argued that free markets, where supply and demand operated without interference, were the most efficient way to allocate resources.

He believed that competition encouraged innovation and productivity, which ultimately led to economic prosperity.

He specifically critiqued mercantilism, which meant that Smith challenged the dominant economic theory of his time, which was based on government regulation and the accumulation of wealth through trade restrictions.

He rejected the idea that nations should prioritize hoarding gold and silver through protectionist policies, arguing that this approach hindered economic growth.

Instead, he advocated for specialization and the division of labor, which increased efficiency and allowed nations to benefit from trade.

Smith’s detailed analysis demonstrated that free trade and open markets encouraged cooperation between nations and created mutual economic advantages.

In fact, Smith’s insights into production, pricing, and market dynamics became the foundation for capitalist economies that emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Governments and economists began adopting policies that reflected his belief in limited interference and economic freedom.

Meanwhile, The Wealth of Nations influenced policymakers in Britain and beyond.

Denis Diderot and the encyclopedia that changed the world

In 1751, Denis Diderot began compiling The Encyclopédie, which was a monumental project aimed at collecting and disseminating the intellectual achievements of the Enlightenment.

As the editor, Diderot worked tirelessly to bring together contributions from leading thinkers, including Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau.

He envisioned the encyclopedia as a tool for challenging ignorance and spreading rational thought.

Comprising 28 volumes by its completion in 1772, the work sought to provide comprehensive knowledge across a wide range of subjects, including philosophy, science, art, and politics.

Through its detailed articles and illustrations, it presented Enlightenment ideals in an accessible and systematic format.

By making advanced ideas available to a broader audience, The Encyclopédie transformed the accessibility of philosophical and scientific knowledge.

Previously, such information had been restricted to universities and elite institutions, which meant that the general public had limited access to new discoveries and ideas.

Thanks to the wide circulation of the encyclopedia, ordinary citizens and professionals could engage with groundbreaking concepts, including critiques of traditional authority and calls for progress.

The work also became a political statement, as many of its entries subtly challenged the Catholic Church and absolute monarchies.

As a result, it faced censorship and opposition from conservative factions, which only heightened its impact as a symbol of intellectual freedom.

Diderot’s efforts influenced the spread of Enlightenment thought across Europe and beyond.

In France, The Encyclopédie inspired debates that would later fuel revolutionary ideas.

Based upon his vision and persistence, Diderot turned an ambitious intellectual project into a powerful tool for change that advanced the Enlightenment’s goals of knowledge and progress.

Did the Enlightenment include women? Mary Wollstonecraft’s answer

Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in the year 1792, which was a bold and systematic critique of societal attitudes toward women.

She argued that women deserved the same education as men. This meant that they could develop their reason and virtue to contribute fully to society.

Wollstonecraft rejected the idea that women should be confined to roles dictated by tradition or superficial accomplishments.

Instead, she emphasized the need for equal opportunities, particularly in education, which she believed was essential for achieving true equality.

By advocating for gender equality in this way, Wollstonecraft expanded Enlightenment ideals to include women.

Enlightenment philosophy often promoted liberty and reason but failed to extend these principles to women.

Wollstonecraft directly confronted this exclusion, arguing that excluding women from political and intellectual life weakened society.

She pointed out that educating women would benefit families and nations, which meant that both individuals and institutions had a stake in promoting equality.

Her ideas reflected the broader Enlightenment commitment to reason and progress, but she applied these principles in a way that highlighted the systemic injustices faced by women.

As a result, Wollstonecraft became an early and influential voice in the development of feminist thought.

Her critique of patriarchal structures inspired later activists and writers, including figures in the 19th-century women’s suffrage movement.

Ultimately, Wollstonecraft’s emphasis on rationality and equal opportunity provided a foundation for ongoing debates about women’s rights.

How did Enlightenment thinkers inspire revolutions?

During the late 18th century, the ideas of Enlightenment thinkers directly influenced political revolutions across the Atlantic world.

The American Revolution, which began in 1775, drew heavily on the writings of John Locke, whose principles of natural rights and government by consent inspired the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Similarly, the French Revolution, which began in 1789, reflected the influence of Rousseau’s concept of the general will and Montesquieu’s separation of powers.

In 1791, the Haitian Revolution became another example of Enlightenment ideals in action, as enslaved individuals fought for liberty and equality.

Clearly, Enlightenment thinkers changed the intellectual foundations of modern political and social systems.

Philosophers such as Voltaire advocated for freedom of speech and religious tolerance, which were later enshrined in democratic constitutions. In particular,

Enlightenment emphasis on reason also encouraged secular approaches to policymaking, which reduced the dominance of religious institutions in political affairs.

However, during the 19th century, critics questioned whether Enlightenment ideals adequately addressed issues of inequality and oppression.

Furthermore, colonial powers often invoked Enlightenment principles to justify imperial expansion, which contradicted the movement’s emphasis on liberty.

These contradictions, which became apparent in practice, sparked debates about the limitations of Enlightenment philosophy.

As a consequence, the movement’s legacy remained influential but also subject to continuous re-evaluation.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.