Steel predators: The silent threat of German U-boats in WWI

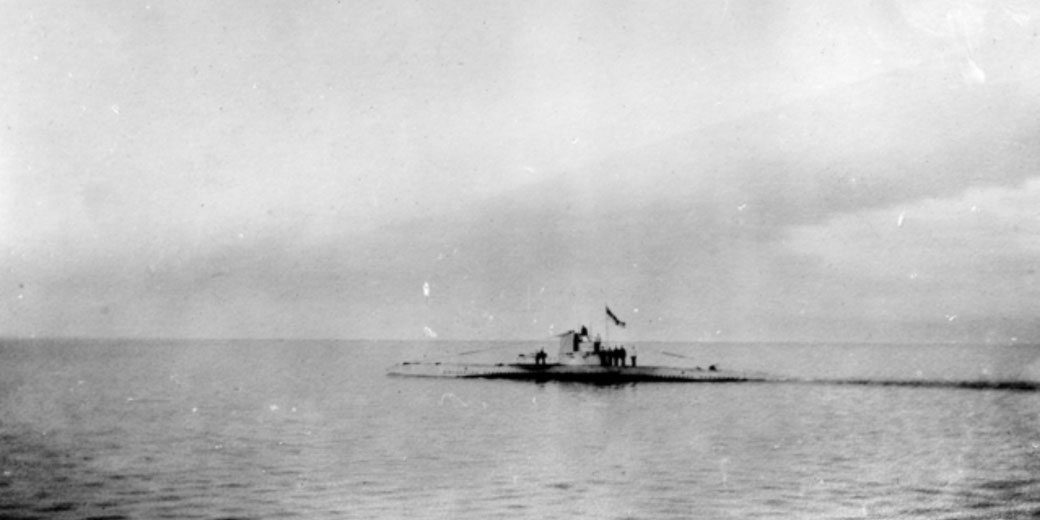

At the dawn of the 20th century, a new weapon emerged from the depths of the ocean, forever altering the course of World War I.

The German U-boat, a stealthy hunter lurking beneath the waves, introduced a level of unseen terror and strategic disruption on the high seas.

As these underwater vessels silently patrolled the Atlantic, they established conventions of maritime combat.

How did these submarines transform the nature of naval warfare?

What innovative tactics and technologies did they employ?

And how did the Allies scramble to adapt to this underwater menace?

What were 'U-boats'?

German U-boats, or Unterseeboote, were specifically designed for stealth and lethality.

Before World War I, surface battleships and cruisers dominated naval warfare, with engagements typically involving direct, visible confrontations between opposing fleets.

However, the advent of the U-boat disrupted this status quo. German U-boats, which were equipped with torpedoes, allowed for a form of warfare that was both secretive and devastating.

Operating unseen beneath the waves, they could attack enemy vessels without warning.

This made these submarines an unpredictable and fearsome adversary.

Initially, the U-boats' initial role was primarily defensive. Their aim was to protect the German coastlines and harbors.

However, as the war progressed, Germany began to deploy them in offensive operations across the broader expanses of the Atlantic.

This shift was partly driven by the British Royal Navy's formidable surface fleet, which significantly outnumbered and outgunned Germany's battleships.

In response, Germany leveraged its U-boats to target Allied merchant and military ships.

Why they were the technical marvel of their age

At the outbreak of the conflict, submarines were relatively primitive; their operational and tactical value was largely unproven.

Early submarines were limited by their rudimentary propulsion systems. They relied heavily on a combination of electric batteries for underwater operation and diesel engines for surface travel.

These initial power sources were inefficient and offered limited range and speed.

However, throughout the war, improvements in engine and battery technology allowed for longer missions.

This increased range and operational flexibility were pivotal in allowing German U-boats to venture far into the Atlantic.

Also, early submarine models were equipped with a limited number of torpedoes. In a similar way, their launch systems were often unreliable.

But, innovations in torpedo technology, including improvements in their accuracy, range, and explosive power, greatly enhanced the offensive capabilities these weapons.

In addition, the development of deck guns on top of the U-boats allowed the submarines to engage targets on the ocean surface in good weather.

The strategic importance of U-boats in WWI

At the onset of the conflict, traditional surface fleets dominated naval warfare.

However, U-boats offered Germany a means to challenge British naval supremacy despite its smaller surface fleet.

As the German U-boats was to disrupt Allied shipping, the hoped to force Britain into submission.

Consequently, U-boats became a constant threat to transatlantic shipping routes.

The unpredictability and stealth of U-boat attacks created a pervasive sense of vulnerability among Allied and neutral shipping.

Fear of U-boat attacks complicated naval operations and merchant shipping, which forced the Allies to devote considerable resources to anti-submarine measures.

The deployment of convoys, development of new detection technologies, and increased naval escorts were direct responses to the U-boat threat.

Moreover, U-boats were used to support the Ottoman Empire, an ally of Germany, by disrupting supply lines to the Middle Eastern theaters.

The brutal nature of unrestricted submarine warfare

The Unrestricted Submarine Warfare Campaign, which began in 1915, was when Germany announced that its U-boats would sink any ship, whether enemy or neutral, found in the war zone around Britain and Ireland.

This decision was a clear departure from established naval warfare norms, particularly those respecting the treatment of neutral and civilian vessels.

The brutality of this tactic became quickly evident. On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sand the RMS Lusitania, a British civilian ocean liner.

The attack resulted in the deaths of 1,198 passengers, including 128 Americans.

In the face of global condemnation, Germany temporarily halted unrestricted submarine warfare to avoid further antagonizing neutral countries, particularly the United States.

However, by early 1917, with the war dragging on and no decisive victory in sight, Germany decided to resume and intensify its unrestricted submarine warfare strategy.

The ultimate goal was to cut off Britain from its overseas resources and force a swift end to the war.

German military leadership believed that by using their U-boats to sever supply lines, they could starve Britain into submission within a few months.

This became increasingly important, as United States was about to join the conflict on the Allies' side.

This renewed campaign had immediate and significant effects. In April 1917 alone, U-boats sank nearly 900,000 tons of Allied and neutral shipping.

This success, however, came at a considerable cost. The indiscriminate nature of the attacks, particularly those on neutral ships, led to severe diplomatic repercussions.

The most notable consequence was the entry of the United States into the war on April 6, 1917.

This was largely in response to the unrestricted submarine warfare and the sinking of several American merchant ships.

How the Allies responded to the U-boat threat

Initially caught off-guard by the effectiveness of the German U-boat campaign, the Allies eventually developed a series of countermeasures that proved crucial in mitigating the threat.

One of the most significant developments was the introduction of the convoy system.

This method involved grouping multiple merchant vessels together and escorting them using warships.

By traveling in groups, the merchant ships could reduce their chances of being targeted individually by submarines.

Additionally, the presence of armed escort ships deterred such enemy attacks.

Initially, there was resistance to this idea, as some naval officers believed that by travelling in larger groups, it would make ships easier targets.

However, the system, fully implemented by the British in May 1917, and significantly reduced losses.

For example, in April 1917, before the convoy system, U-boats sank nearly 900,000 tons of Allied shipping.

However, by July, monthly losses had dropped to around 500,000 tons.

Another key aspect of the Allied response was technological innovation. The development of depth charges, first used in combat by the British in March 1916, provided an effective means of attacking submerged submarines.

Hydrophone systems, which detected the sound of U-boat engines, and improved sonar technology, also played crucial roles in locating and attacking U-boats.

To help out, the American Navy provided additional ships for convoy escorts. They also introduced tactics like the "hunter-killer" groups, which actively sought out and engaged U-boats.

Air patrols were another innovative response to the threat. By 1918, aircraft were increasingly used to spot U-boats and direct naval forces to their locations.

Although the effectiveness of aircraft in directly damaging U-boats was limited, their presence increased the risk to submarines operating near the surface.

This forced them to spend more time submerged, where they were less effective.

The decline and end of the U-boat menace

By 1918, the effectiveness of German U-boats had significantly diminished, culminating in the end of their dominance in the Atlantic.

The German Navy's own shortcomings contributed to this decline. The high demand for U-boat operations led to rapid production and deployment, often at the expense of training and maintenance.

The U-boat campaign officially ended with the Armistice of November 11, 1918.

The terms of the armistice required Germany to surrender its U-boats, and in total, 176 German submarines were handed over to the Allies.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.