Who was Karl Marx, the man who created communism?

Karl Marx is a rare historical figure: one who has become famous, not for his great acts or achievements, but for his thoughts.

Marx's ideas ignited revolutions and sparked debates that continue to this day.

He was born in 1818 in Trier, Germany. However, Marx's journey from a relatively obscure philosopher to a key architect of modern socialist thought is an incredible story.

Ultimately, his writings challenged the foundation and structure of modern societies.

But what personal experiences shaped his radical viewpoints?

And how did his friendship with Friedrich Engels influence his work?

Marx's early life, family, and education

Karl Marx was born into a middle-class Jewish family. He would be the oldest surviving son of Heinrich and Henrietta Marx.

His father was a lawyer who converted to Lutheranism in order to continue practicing law.

This was the direct result of the societal pressures of the time.

However, this early brush with religious and social constraints subtly influenced Marx's later views on institutions and power structures.

Young Karl Marx attended the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium for his school, where he was immersed in classical literature and philosophy.

Then, in 1835, at just 17, Marx began his tertiary studies at the University of Bonn.

He studied law, which was a path chosen more by his father’s wishes than his own inclinations.

While his time at Bonn was generally typical for most student, suffered a minor wound in a duel while he was a member atthe Trier Tavern Club.

However, realizing that Bonn's environment was more boisterous than beneficial, Marx's parents transferred him to the more serious University of Berlin in the following year.

It was in the subsequent intellectual hotbed of Berlin that Marx's true passions began to surface; he dove deeply into philosophy and works of G.W.F. Hegel.

In particular, Hegel's dialectical method, which argued that societal progress occurs through a conflict of opposing forces, profoundly impacted Marx's thinking.

As a consequent, he joined a group known as the Young Hegelians, who critically engaged with Hegel's ideas.

This group often opposed established religious and political views.

By 1841, Marx completed his doctoral thesis on the philosophy of nature in ancient Greece, titled "The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature."

Despite its academic excellence, his thesis was considered too controversial for the conservative faculty at the University of Berlin.

Consequently, he submitted it to the more liberal University of Jena, which awarded him a PhD in absentia.

How Karl Marx's views developed over time

Marx's immersion in Hegelian philosophy at the University of Berlin had already set the stage for this transformation; however, Marx diverged from Hegel's idealistic interpretation of reality, which centered on ideas shaping the world, and moved towards a materialistic approach.

In this way, he emphasized the primacy of the physical and economic conditions of life instead.

Then, Marx moved to Cologne in 1842 and began working as a journalist for the Rheinische Zeitung, a liberal newspaper.

Here, he began to apply his philosophical ideas to critique contemporary political and social issues.

He wrote on a broad sweep of topics, including poverty, censorship, and the conditions of workers.

His articles, which became increasingly radical, drew the attention of the Prussian government.

As a result, the newspaper was officially suppressed in 1843. This highlighted for Marx the negative power of the state and its ability to control and suppress dissent.

Consequently, Marx moved to Paris in 1844. At the time, the city was a center of socialist thought and he encountered various socialist and communist activists.

Quite rapidly, Max experienced a deepening of his commitment to a revolutionary approach to social change.

His collaboration with Friedrich Engels

Marx had first met Engels in 1842 in Cologne. However, it was during Engels' visit to Paris in 1844 that their lifelong partnership truly began.

Engels, having worked in his family's business in Manchester, England, brought with him firsthand observations of the cruel working conditions in the industrial heartland of the British Empire.

This experience was finally documented in his book "The Condition of the Working Class in England" (1845).

The details it included provided Marx with a concrete empirical basis for his critique of capitalism.

As a result, Marx's theoretical understanding of philosophy, economics, and history, was complemented by Engels' practical insights and organizational skills.

The two men produced their first co-authored work in 1845 called "The Holy Family", which was a critique of the Young Hegelians and contemporary bourgeois society.

This work was considered to be a success and would lay the groundwork for their later, much more significant collaborations.

How Marx saw the world

Importantly, it was in Paris that Marx refined his theory of 'historical materialism'.

This theory argued that the material conditions of a society's mode of production fundamentally determined its organization and development.

According to Marx, history progresses through a series of stages characterized by different modes of production.

Each stage contains a number of internal contradictions that will ultimately lead to its eventual downfall.

Once that happens, it is replaced by a new stage.

In his view, the capitalist system, which relies upon the exploitation of the working class (proletariat) by the owners of the means of production (bourgeoisie), would inevitably lead to a proletarian revolution.

However, Marx's stay in Paris was cut short in 1845 due to his expulsion by the French government, who had been put under pressure from Prussia to do so.

So, he moved to Brussels, where he continued his writings and further developed his ideas in collaboration with Engels.

During this time, he focused on writing of "The German Ideology" (1845). It would remain unpublished, but in it, Marx and Engels laid out the principles of what later became known as 'Marxism'.

At its core, it critiqued earlier German philosophy, and provided a materialist understanding of history and society, as outlined earlier.

Marx's growing political activism

While in Brussels, Marx also began to actively participate in socialist groups. In 1847, both Marx and Engels joined the Communist League, which was an international group of socialists who sought to encourage social revolutions in countries around the world.

This membership was a significant step in Marx's political activism, as he was now part of an organization actively seeking to implement socialist ideas.

Knowing their literary capabilities, the League commissioned both him and Engels to write a manifesto that would succinctly articulate their political principles.

Ultimately, this task led to the creation of the "Communist Manifesto," published in 1848, which has become the most famous of all of Marx's writings.

This brief document argued that all of human history was the history of class struggles and predicting the eventual victory of the proletariat over the bourgeoisie.

As a side note, the year 1848 was also significant due to the wave of revolutions that swept across Europe.

The revolutions, which were driven by a mix of economic hardship and demands for political reform seemed to confirm all of Marx's ideas about class struggle and the need for revolutionary change.

At the time the revolutions were breaking out, Marx returned to Cologne in April 1848.

It was here that he started the Neue Rheinische Zeitung: a newspaper that was intended to become a mouthpiece for his revolutionary ideas.

However, the eventual failure of the 1848 revolutions and subsequent political repression led to another expulsion for Marx.

In 1849, he was forced to leave Germany and move to London, where he would spend the rest of his life.

In London, Marx's political activism took a slightly different turn. The distance from mainly Europe meant that he was no longer directly involved in revolutionary activities.

So, instead, he focused more on theoretical work and played a significant role in the International Workingmen's Association (also known as the First International), which was founded in 1864.

The First International brought together various socialist, communist, and anarchist groups.

It would become a central hub for the international labor movement.

Marx's personal contributions to the First International were relatively significant.

He wrote its inaugural address and a host of other documents that shaped the overall direction of the organization that would become influential for the next decade.

However, internal conflicts, particularly disputes with anarchist factions led by Mikhail Bakunin, eventually led to the dissolution of the International in 1876.

Marx's other important written works

As mentioned earlier, Marx's most significant work was "The Communist Manifesto".

However, it is "Das Kapital" that stands as Marx's most profound contribution to economic theory and critique of capitalism.

The first volume, published in 1867, undertakes a detailed analysis of capitalist production. It also lays out his theory of surplus value, which suggests that the value of a product is determined by the labor required to produce it.

As a result, any profit in capitalist society comes from the exploitation of labor, as workers are paid less than the value they produce.

The subsequent volumes of "Das Kapital," edited and published posthumously by Engels, delved further into the processes of capitalist production: specifically, circulation and the overall dynamics of the capitalist system.

How his personal life influenced his work

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen in 1843: a union that is often said was both a romantic and intellectual partnership.

Jenny came from an aristocratic Prussian family, and she became a significant influence and steadfast support in Marx's life.

They had seven children together, although only three survived to adulthood — Jenny, Laura, and Eleanor.

What is often forgotten in biographies of Marx is how much the loss of their children, including the death of their son Edgar at age eight, was a source of deep sorrow for Marx and his wife.

Unfortunately, financial instability was a constant pressure in Marx's life. It was only exacerbated by his political activities and frequent exiles.

While in London in particular, his family lived in poverty for many years. As is to be expected, Jenny often struggled to manage the household in these dire financial conditions.

However, Friedrich Engels generously provided much-needed financial support, which was crucial in allowing Marx to continue his work.

Also, Marx suffered from deteriorating health, as he suffered from various ailments like liver and respiratory problems.

These were likely aggravated by his intense work habits and the increasingly poor living conditions his family endured.

However, despite these many challenges, Marx remained deeply committed to his work and often sacrificed his health in the process.

Marx's later years and death

After settling in London in 1849, Marx spent the remainder of his life there, dedicating himself to extensive research and writing.

Sadly, Jenny passed away in December 1881, and his eldest daughter, Jenny Longuet, also died in January 1883.

Obviously, these personal losses deeply affected Marx.

However, Marx remained intellectually active. He continued to correspond with fellow socialists and intellectuals, staying committed to providing guidance and commentary on the international workers' movement.

In addition, he closely followed and commented on events such as the Paris Commune of 1871, an uprising of the Parisian working class.

Then, Karl Marx passed away on March 14, 1883, in London, at the age of 64. His death was apparently attributed to bronchitis and pleurisy.

These were health conditions he had battled for several years.

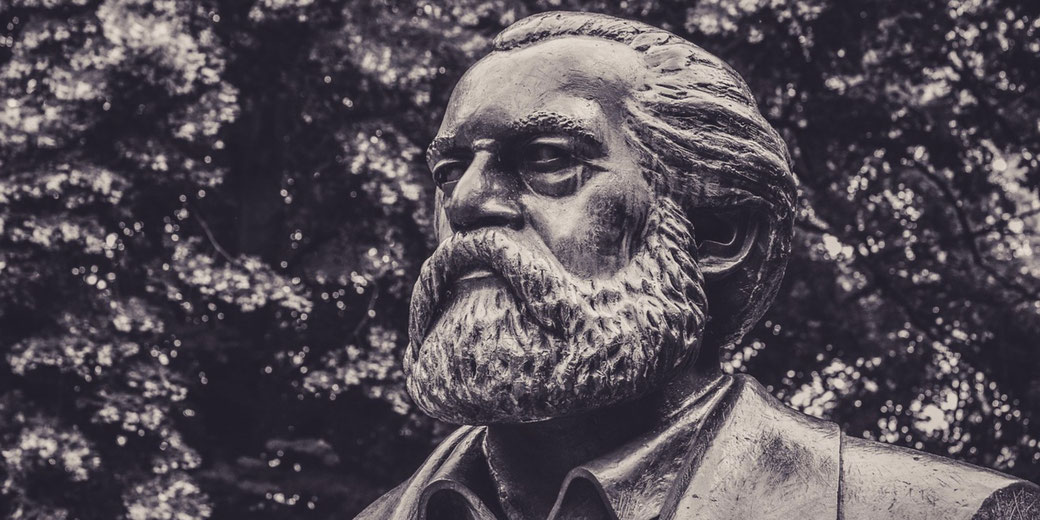

Marx's eventual passing was mourned by socialists and workers worldwide, and he was finally buried at Highgate Cemetery in London.

His grave, which became a monument that includes a large bust of Marx, has since become a sombre site of pilgrimage for those inspired by his ideas.

Why Karl Marx is an important historical figure

Marx's critique of capitalism, with its focus on the exploitation inherent in the system and the concept of class struggle, provided a comprehensive framework that has been adopted and adapted by various political movements and governments, particularly during the 20th century.

As a result, the Russian Revolution of 1917 was one of the most significant direct applications of Marx's theories.

Russia, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, saw the Bolsheviks seek to create a society based on mainly on Marxist principles.

This turning point had a significant ripple effect by inspiring numerous other socialist and communist movements worldwide: from China to Cuba, and various countries in Africa and Latin America.

Al of these movements adopted Marx's critiques, although they often adapted his ideas to fit their specific national and cultural contexts.

What is more important, is that his ideas have profoundly influenced several academic disciplines, including sociology and economics.

The concepts of class conflict, alienation, and historical materialism have since become foundational elements in these fields.

Critical theory, for instance, which emerged in the mid-20th century, drew heavily on Marx's ideology.

However, Marx's legacy is controversial. The implementation of Marxist principles in various countries, particularly in the form of Soviet-style communism, has been critiqued for authoritarian practices.

In addition, in countries which have openly adopted his ideas have been guilty of vast economic inefficiencies and human rights violations.

This has fueled ongoing debates about the real interpretation of Marx's ideas and their application in practice.

To what extent is Marx directly responsible for these problems, or is it simply due to those who implemented them erroneosly?

Maybe only time will tell.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.