Voyages of despair: The harsh reality of life aboard 18th century convict ships to Australia

There's a gruesome story at the heart of modern Australian history, a whisper of shackles and sails, borne of an era when Britain sought to alleviate its overflowing prisons by banishing convicts to the farthest reaches of its empire.

Between 1788 and 1868, over 160,000 people were dispatched on an epic journey across perilous seas to a land almost beyond imagination.

But what was life truly like within the dank confines of these floating prisons?

And how did the convicts endure the trials of their sea voyage and the realities of an unknown land?

Welcome aboard, prisoner...

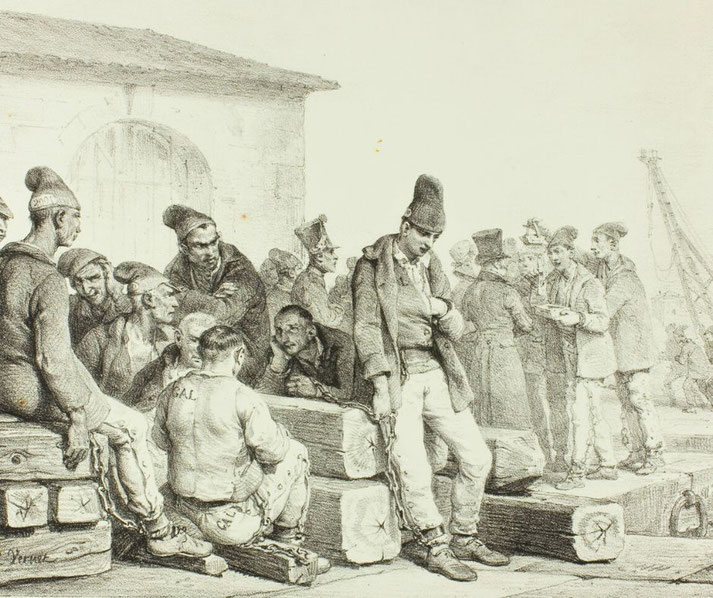

The moment of embarkation marked the beginning of a journey full of uncertainty, hardship, and survival.

Men, women, and sometimes children, convicted for crimes ranging from petty theft to murder, were uprooted from their homes, thrust into the gloom of ship holds, and set sail for a distant land.

Conditions aboard the convict ships varied, but a common theme was overcrowding.

The hulks were often crammed with individuals chained together, the pungent scent of unwashed bodies, illness, and despair permeating the atmosphere.

Convicts were typically held below decks, their quarters being poorly ventilated, dark, and damp.

How bad were the conditions?

Hygiene was a major concern, with scurvy and dysentery being common maladies due to a lack of fresh fruits and vegetables and unsanitary conditions.

Despite this, ship surgeons did their best to preserve the health of the convicts, their efforts often influenced by a monetary incentive - they were paid based upon the number of convicts who arrived alive.

Daily life was regimented, including forced exercise on deck when weather allowed, and meals that were basic and monotonous.

Hardtack biscuits, salted meat, peas, and oatmeal made up the typical diet. Punishments for misconduct were harsh and could include flogging, solitary confinement, or the withholding of rations.

The mental toll was equally severe. Many convicts, disoriented by the rolling waves and sickened by their conditions, succumbed to melancholy and despair.

Some turned to religion for solace, with ship chaplains providing spiritual guidance.

Others took solace in companionship, creating bonds with fellow convicts.

Attempts to improve things

Despite these hardships, the journey also marked the start of new lives for many convicts.

The threat of rebellion was ever-present, as convicts found themselves in a social hierarchy where solidarity was sometimes stronger than the chains that bound them.

Notable mutinies such as those on the ships Hercules in 1802 and the Batavia in 1829 underscored the convicts’ desperate yearning for freedom.

Over time, regulations were introduced to improve the conditions aboard these ships.

The 'Surgeon's Charter' of 1802 decreed that every convict ship should have a surgeon on board, that convicts should be given adequate food and water, and that women should be overseen by a matron.

By the mid-19th century, the conditions had markedly improved, with mortality rates dropping significantly.

The journey on a convict ship to Australia was one of the most challenging experiences that a person could undergo in the 18th and 19th centuries.

It was a journey filled with hardship and deprivation, yet it was also a transformative one. As Australia evolved from a penal colony to an independent nation, these former convicts and their descendants would form the backbone of a burgeoning society.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.