Destroy the machines! The Luddites' violent reaction to new technology.

During the early 1800s, Britain entered a new industrial age that changed how goods were made and how labour was valued.

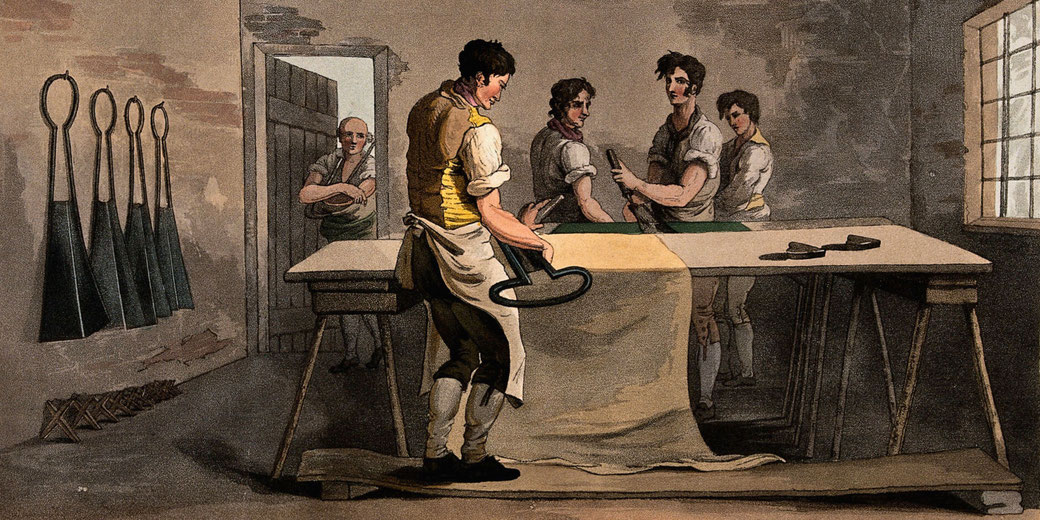

Textile factories, which had once relied on skilled handloom weavers, were increasingly filled with machines such as the spinning mule, power loom, and water frame, which had evolved from earlier innovations like the spinning jenny.

Factory owners often used these inventions to increase output and reduce costs during the hardship of the Napoleonic Wars, which placed a great strain on the economy through trade blockades and inflation that led to severe food shortages.

Victims of progress?

As machines replaced skilled workers in many areas, thousands of men lost their livelihoods.

The value of craftsmanship often fell, and in many places wages collapsed. Many workers, once respected in their communities for their trade, now found themselves forced to compete with unskilled labourers, including women and children, who could operate machines for a fraction of the cost.

For this reason, resentment built in many towns across Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and Lancashire.

No legal help was generally available, and their protests received little sympathy from employers.

When economic despair offered no peaceful outlet, some workers turned to violence.

The formation of the Luddite movement

Organised resistance first appeared in 1811 when machine-breaking began in Nottinghamshire.

Protesters destroyed stocking frames that were used in the hosiery trade and signed letters in the name of “Ned Ludd.”

No reliable record confirmed that 'Ned Ludd' existed. Some accounts claimed he was a Leicestershire apprentice who smashed a frame in 1779, but that story likely came later and was probably invented.

Regardless of historical accuracy, he became a widely recognised symbol of defiance.

His name gave frightened and angry workers a cause to unite around and an identity that the authorities could not easily stop.

Because factory owners had often ignored written appeals and had continued to use machines that undercut wages, Luddites increased their response.

They targeted specific workshops that had dismissed experienced artisans or had reduced pay to near-starvation levels.

Under those conditions, they believed that the agreements between master and craftsman had been broken.

As a result, In many instances, machine-breaking became a form of economic protest.

Rather than acting at random, Luddites aimed their destruction at machines that had displaced honest labour.

The rapid spread of their violent protests

As news of the Nottinghamshire attacks spread, Luddite activity reached Yorkshire in February 1812 and Lancashire shortly afterwards.

Raids had begun to occur more frequently and had involved increasingly larger groups of masked men.

When they struck at night and destroyed power looms and spinning frames in places like Leeds and Huddersfield, Luddites made sure their actions could not be ignored.

At the same time, mill owners increased security by hiring guards, and they also appealed to the government for help.

Tensions reached a peak in April 1812 with the attack on Rawfolds Mill near Huddersfield.

William Cartwright, who owned the mill, had expected an attack, so he stationed armed guards and soldiers inside the building.

When the Luddites arrived, a violent skirmish broke out and two of the attackers, John Booth and Samuel Hartley, were killed, while many others were wounded.

The failed raid showed that factory owners would no longer stand by passively.

They now fought back with deadly force.

Shortly afterward, a group of Luddites ambushed and killed William Horsfall, a manufacturer who had openly condemned their cause and boasted that he would ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood.

His assassination, which took place near Huddersfield on April 28, confirmed that the unrest had moved from property damage into targeted political violence.

Because of this escalation, local officials demanded wider powers, and the government largely responded with harsh measures.

How the British government tried to stop the Luddites

In 1812, Parliament introduced the Frame Breaking Act, which made the destruction of industrial machinery a capital crime.

Government ministers argued that such harsh punishment was necessary to restore order and protect economic progress.

For this reason, the law permitted execution for machine-breaking, even if no one had been injured during the act.

To enforce the law, the government sent more than 12,000 troops into areas affected by Luddite attacks, a domestic deployment that matched the size of some expeditionary forces then engaged against Napoleon on the Iberian Peninsula.

As troops entered manufacturing towns across Yorkshire, Lancashire, and the Midlands, magistrates had issued arrest warrants, had raided homes, and had paid informants to identify suspected ringleaders.

At the same time, government spies and undercover agents posed as members of Luddite groups to gather intelligence, and several informants, who played important roles in identifying local organisers, helped to find them.

Because the government feared a wider rebellion, it largely treated the movement as a direct threat to the state rather than a protest against unemployment.

Captured Luddites were tried in heavily guarded courtrooms. In many cases, prosecutors had relied on witness testimony from paid informants.

Trials had generally been swift and punishments had often been harsh. Dozens of men had received sentences of transportation to penal colonies in Australia, including New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land (later renamed Tasmania), where difficult conditions often amounted to lifelong exile.

Others had been publicly hanged in towns like York and Lancaster to deter further resistance.

As a result, fear spread among workers, and open defiance became increasingly rare.

What happened to the Luddites?

By 1813, the Luddite movement had largely collapsed under the weight of government repression.

The public hangings, mass arrests, and widespread troop deployments left no space for organised resistance.

At the York Assizes in January of that year, twelve convicted Luddites, including George Mellor, Thomas Smith, and William Thorpe, were executed.

Their deaths, which were intended as a public warning, ended the most violent phase of the protests.

Afterward, industrialisation continued quickly in many regions as machines replaced more skilled workers, and wages remained low across the textile industry.

Most of the surviving Luddites had returned to whatever work they could find, often under worse conditions than before.

Others, unable to adapt, sank into long-term poverty. The world they had tried to defend, which was based on mutual obligation between master and craftsman, disappeared.

Despite their failure, the Luddites forced people to consider the human cost of economic change.

Their story showed how industrial advancement, which was often introduced without protections or compassion, could sometimes destroy entire communities.

For this reason, the memory of their rebellion lasted in some communities.

Why the Luddites still impact us today

Over time, the word “Luddite” became a label used to mock those who question or oppose new technology, but that meaning ignores the original movement’s purpose.

The Luddites did not resist innovation because they feared change. They resisted because the change had largely impoverished them while enriching others.

They demanded fair wages and job security and insisted that skilled labour should receive respect.

Since they received none of these, they fought back.

In the present day, new forms of automation and artificial intelligence threaten many jobs in transport, retail, logistics, and manufacturing.

Driverless trucks, self-service checkouts, and AI-generated journalism now raise the same fears of redundancy that once haunted textile workers.

Workers who fear replacement face the same uncertainty that haunted the Luddites two centuries ago.

As machines continue to change economies, many still ask who benefits from this progress and who pays the price.

Historians now view the Luddites not as irrational saboteurs but as early voices in the long debate over the ethics of industrial capitalism.

Writers such as E.P. Thompson, in works like The Making of the English Working Class, have argued that the Luddites acted with reason and purpose.

They ultimately failed to stop the march of mechanisation. They exposed the danger of ignoring the workers whose lives changed because of it.

Their protests, which echo in every age of major technological change, remind us that the future must be planned with justice as well as profit in mind.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.