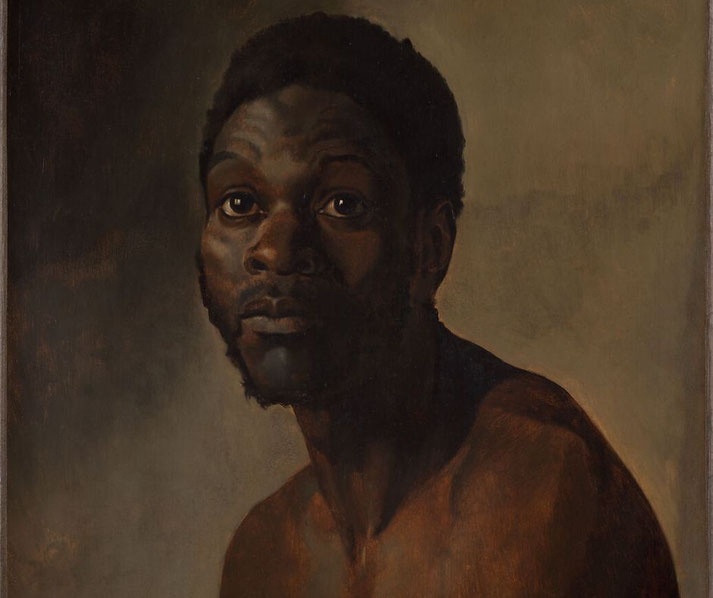

The horrifying reality for the enslaved people transported across the Middle Passage

For millions of enslaved Africans, the Middle Passage was a journey of unimaginable suffering: packed tightly into the filthy holds of European ships, they endured weeks of hunger, disease, and violence.

Death hovered over them at every moment as the air reeked of human waste and decay. Those who survived the passage faced an unknown future, their fates decided by the whim of a brutal system.

The Middle Passage was a human tragedy that helped fuel the economies of the New World but left behind a legacy of pain and exploitation.

What was the Middle Passage?

The Middle Passage referred to the harrowing sea voyage that transported enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas.

It was the central leg of the triangular trade that linked Europe, Africa, and the New World.

During this journey, ships carried human cargo from African ports, where millions had already faced violent capture or coercive sale, in horrifically overcrowded ships.

Simply put, European merchants profited enormously from this leg of the trade by buying and selling enslaved individuals as commodities for labor in the sugar plantations, tobacco fields, and other industries of the American colonies.

To fund the purchase of other human beings like this, European goods such as textiles, firearms, and manufactured items were traded in Africa for the enslaved individuals, who were then shipped across the Atlantic.

Once they reached the New World, these Africans were sold into slavery, and the ships then returned to Europe laden with valuable colonial produce, including sugar, cotton, and tobacco.

As a result, the Middle Passage facilitated the rapid growth of plantation economies in the Americas, which were heavily reliant on slave labor.

How were people captured and sold into slavery?

People were captured and sold into slavery through a violent and systematic process that often began deep within the African continent itself.

In many cases, African rulers played a significant role in the capture and sale of enslaved people.

Leaders like King Tegbesu of Dahomey, who was heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade during the 18th century, built wealth and power through their participation.

Some kingdoms, such as the Oyo Empire and the Ashanti Confederacy, became major players in the export of human lives.

However, it also meant that local rulers and warlords frequently waged wars of expansion to capture new prisoners.

Ultimately, it was European demand for labor drove much of this violence, and African leaders exploited these opportunities to strengthen their own political power.

Raiding parties that were organized by these local leaders or rival groups would descend upon villages where they would seize men, women, and children.

These raids were swift and brutal and left devastation in their wake. Once captured, enslaved individuals were subjected to dehumanizing treatment as they were prepared for sale.

They were often branded with hot irons to signify their ownership. The captives were then marched to the coast, sometimes for hundreds of miles, in chains.

Sadly, many did not survive the journey.

Once the survivors arrived at the coastal trading posts, they were sold to European traders and placed in makeshift barracks or dungeons along the coast, awaiting the arrival of European ships.

The infamous ‘Slave Coast’ of West Africa, particularly areas like Elmina Castle in modern-day Ghana, became hubs for this trade.

Here, European traders worked closely with local rulers to negotiate the purchase of enslaved people, who would then be forced aboard the ships for the Middle Passage.

Packed like cargo: Conditions aboard the slave ships

Aboard the slave ships, conditions were atrociously overcrowded. Captains packed as many enslaved people as possible into the lower decks to maximize profit, which often meant that each person had less than five feet of horizontal space and barely three feet of vertical space.

Men, women, and children were chained together, with no room to move or lie comfortably.

Forced into such confined spaces for weeks or months, the enslaved endured unimaginable discomfort.

Captives had to relieve themselves where they sat or lay. The lack of ventilation in the ship's hold made the air stifling and thick with the stench of human waste.

Enslaved people were often fed only once or twice a day and received meager portions of rice, yams, or beans.

These rations were barely enough to sustain life and were often of such poor quality that many captives found them inedible.

Furthermore, dehydration became a significant issue, as water supplies were limited and often tainted.

As days turned into weeks, the lack of nutrition and clean water caused many to grow weak.

This made them even more vulnerable to disease.

Furthermore, the psychological toll on enslaved individuals began the moment they were captured, especially given the fear as they faced the terrifying unknown of being torn from their homes and communities.

Many feared not only for their lives but also for their dignity, knowing they had no control over their fate.

The trauma of family separation only compounded this anguish. They were often torn from their spouses and children, as well as their communities.

In fact, this disintegration of familial and social bonds was deliberate, as it was designed to weaken resistance and prevent unity among the enslaved.

Why did so many die on the Middle Passage?

Mortality rates during the Middle Passage were alarmingly high due to the spread of common diseases.

Confined to the cramped and unsanitary holds of ships, enslaved individuals were exposed to rampant infections that thrived in such conditions.

Diseases like dysentery, which was often referred to as ‘the bloody flux’, spread quickly through the close quarters, which was exacerbated by the lack of hygiene and fresh air.

Smallpox, measles, and scurvy also claimed many lives. Sadly, the absence of basic medical care meant that even minor infections could prove fatal.

Estimates suggest that up to 15% of all captives died from disease during the voyage, with some ships losing nearly half their human cargo to illness alone.

Then, starvation and suicide also contributed significantly to the high death toll on board.

As a way of maximizing profit, ships captains often rationed food sparingly. Some enslaved individuals refused to eat in an act of defiance, preferring death to the horrors of enslavement.

In response, crews resorted to brutal force-feeding, using devices like metal ‘speculums oris’ to pry open the mouths of those who resisted.

Suicide, though difficult to quantify, was common. Many enslaved people threw themselves overboard in a desperate bid to escape their fate, sometimes chained together in large groups.

Punishment for attempted rebellion or resistance was severe, and the routine use of flogging and torture led to additional deaths during the passage.

Across the duration of the transatlantic slave trade, it is estimated that between 1.8 and 2 million enslaved Africans perished during the Middle Passage.

These deaths accounted for approximately 10-20% of those forcibly transported across the Atlantic.

Some voyages saw even higher losses, especially when ships encountered storms or prolonged delays, which worsened the already dire conditions on board.

Did slaves fight back?

Acts of defiance began almost immediately after capture and continued on board the ships.

Many enslaved people engaged in silent acts of resistance, such as attempting to break their shackles or sabotage the ship’s equipment.

Some women who were forced into sexual exploitation by the crew resisted through physical struggle or by attempting to harm their captors.

Larger scale revolts aboard slave ships were perhaps the most dramatic form of resistance.

Some organized mutinies involving dozens or even hundreds of people. One well-known example occurred on the ship Amistad in 1839, where captives led by Sengbe Pieh (also known as Joseph Cinqué) successfully overthrew the ship’s crew.

Though the Amistad rebellion took place later in the history of the slave trade, it represented the general desperation and courage of those who revolted on many other vessels.

Another, on the Little George in 1730, became famous when captives overtook the vessel before being recaptured by the crew.

The outcomes of these rebellions varied, as some were brutally suppressed, with captives being killed or thrown overboard as punishment, while others, like the Amistad revolt, ended in legal battles and freedom for those involved.

Even when revolts failed, the threat of rebellion terrified European crews. As such, captains took extreme precautions, such as keeping the enslaved chained in pairs, restricting their movement on deck, and arming themselves heavily to prevent mutinies.

Such revolts disrupted the trade and sometimes caused financial losses for the slave traders, which made them fear the potential for uprising at any moment.

What were the crews and slave traders like?

In general, crewmen saw enslaved people as cargo rather than human beings, which meant they were treated with ruthless disregard.

Officers and sailors were responsible for maintaining order on board, which often translated into the use of extreme force: regular beatings and physical abuse.

Crews were tasked with overseeing the daily management of hundreds of captives, and, in their view, violence was a necessary tool to control a population they perceived as rebellious and dangerous.

Many captains, such as Captain Hugh Crow, who was known for his involvement in the late 18th-century slave trade, emphasized strict discipline to prevent rebellion.

His officers organized frequent inspections to ensure the enslaved remained shackled and controlled and the crew members received orders to flog anyone who appeared uncooperative.

As a result, the crew’s constant readiness to employ violence created a volatile environment on board, where any sign of dissent could result in swift and brutal retaliation.

Furthermore, the crew members themselves, particularly those of lower social status, frequently suffered from some of the same poor conditions and harsh discipline.

Many sailors, such as those employed on ships owned by traders like John Newton, who later became a vocal critic of the slave trade, endured brutal working environments.

As a consequence, these sailors felt like they had no choice but to lash out at the captives under their watch.

What happened when they arrived in the Americas?

Upon arrival in the Americas, enslaved Africans underwent a harsh ‘seasoning’ period that was aimed at preparing them for their future roles as laborers.

This process took place on plantations or in slave camps, primarily in locations such as the Caribbean islands or the southern colonies of North America.

During this period, overseers forced the enslaved to adapt to new labor systems, language, and environmental conditions.

Many enslaved individuals, who were already weakened by the Middle Passage, struggled to survive this additional period of intense exposure.

As a result, mortality rates remained high, as the physical and emotional trauma continued to break down their bodies and spirits.

The ‘seasoning’ process also involved separating those who were deemed more ‘compliant’ from those who showed resistance.

Once seasoned, enslaved people were sold through auctions that often took place in major ports like Charleston in the American colonies or Kingston in Jamaica.

Captives were paraded before potential buyers, examined like livestock, and often subjected to humiliating inspections of their bodies.

Families that had managed to survive together during the voyage were routinely torn apart during this process.

The buyers specifically selected individuals based on age, sex, and physical condition, which meant that children were separated from their parents and siblings from one another.

After the auction, enslaved Africans were transported to their new homes, often on plantations across the southern United States, Brazil, or the Caribbean.

There, they were subjected to further dehumanization as they were integrated into the brutal labor systems of sugar, cotton, or tobacco production.

The process of family separation did not end at the auction block. Many enslaved individuals faced repeated sales and separations throughout their lives, depending on their owners' financial status or the success of the plantation.

In these regions, places like Virginia and Louisiana became infamous for their role in expanding the internal slave markets.

The long shadow of the Middle Passage on the world

The long-term consequences of the Middle Passage on African societies were devastating and far-reaching.

Entire regions suffered population loss due to the capture and exportation of millions of people.

Many communities faced repeated raids, which led to the collapse of local economies and social structures.

As a result, villages were abandoned, and warfare between neighboring groups increased as rival factions sought to capture more individuals for trade.

This disruption weakened many African kingdoms, particularly those that resisted involvement in the slave trade.

For example, regions like the Congo Basin experienced profound instability as powerful states like the Kingdom of Kongo fragmented under the pressures of internal conflict and external European demand for slaves.

In the Americas, the arrival of enslaved Africans provided a constant source of labor for plantations, which were essential to the production of cash crops such as sugar, cotton, and tobacco.

As a result, wealthy plantation owners accumulated vast fortunes, which enabled the expansion of European colonial empires.

Also, the reliance on slave labor entrenched racial hierarchies within colonial societies, and created a deeply stratified social order based on race.

In places like Virginia, where large-scale tobacco plantations dominated the economy, enslaved Africans became the foundation of agricultural production.

This led to the development of laws that institutionalized slavery and racial discrimination.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.