Why the widespread revolutions of 1848 failed

The year 1848 witnessed a sudden wave of political revolutions that swept across Europe like wildfire. During this year, the continent was engulfed in turmoil, as the common people cried out for constitutional reforms in their lands, as well as economic relief.

In many cities, the citizens rose up against particularly oppressive leaders by demanding greater freedoms and national unity.

At one point, the unrest led to the fall of the French monarchy, while the German states faced fierce opposition from conservative forces, and the Austrian Empire feared that its empire would fracture along ethnic lines.

Ultimately, however, the Revolutions of 1848, despite their initial promise, were swiftly crushed.

So, what went wrong?

What caused the revolutions of 1848?

In the years leading up to 1848 Europe was experiencing widespread social, economic, and political unrest.

The continent was grappling with rapid industrialization, which had brought significant economic changes as rich company owners profited while the poorer working class suffered.

This led to stark class divisions. Many workers lived in grim conditions, facing low wages and poor working environments.

To add to their plight, between 1845 and 1847, Europe experienced a severe economic crisis, with poor harvests (such as the potato blight of 1845) that led to food shortages, rising grain prices, and increased discontent.

As unhappiness increased, various governments had to rely upon political repression to maintain control.

In fact, the absolute monarchies and conservative governments often used censorship and secret police to stifle any dissent from their own people.

Regardless, demands for political reform and national self-determination grew louder.

By the start of 1848, these simmering tensions were about to erupt into full-scale revolts.

How events in France began the revolutions

The final trigger for the revolutions was the French Revolution of February 1848.

On February 22, thousands of Parisians took to the streets to protest against King Louis Philippe's government, which had banned a political banquet where opposition leaders planned to demand electoral reforms.

The protesters demanded the same political reforms and an end to government corruption.

By February 24, the pressure mounted, and King Louis Philippe decided to abdicate the throne. He fled to England for safety.

In his place, a provisional government was quickly formed on the same day, which proclaimed the creation of the Second Republic.

Under this new government, France saw the implementation of several progressive reforms.

Universal male suffrage was introduced: this allowed more citizens to participate in the political process.

Furthermore, the new republic aimed to address unemployment in Paris by establishing the National Workshops to provide wages for poor workers.

The workshops initially employed several thousand people, but their numbers grew rapidly and reached over 100,000 by June 1848 which had cost 14 million francs.

This strained government finances and rumors began to spread that the program would be cancelled.

Tensions escalated when the government decided to close the National Workshops on June 21.

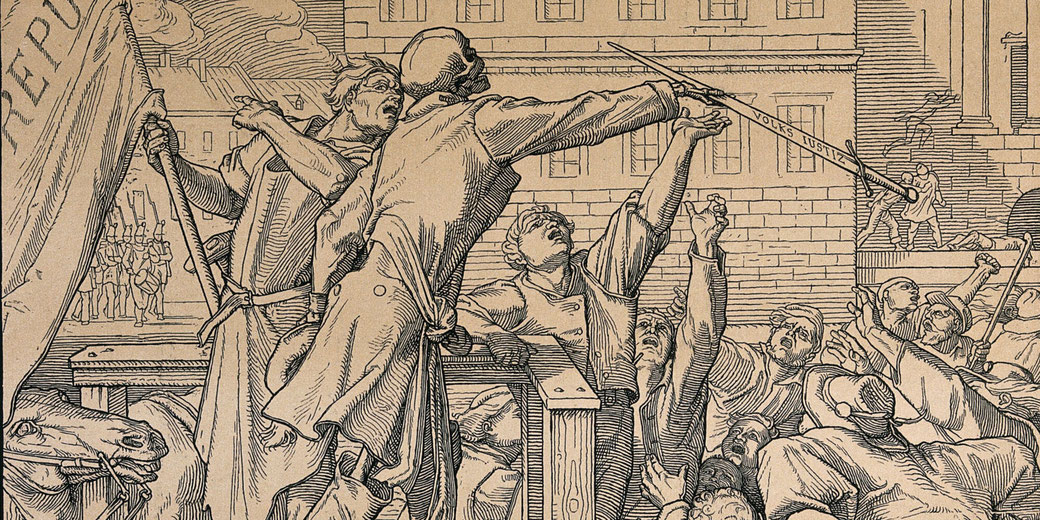

The widespread outrage among the workers led to the violent June Days Uprising from June 23 to June 26, during which time Paris witnessed brutal street battles between the workers and government forces.

By the end of the conflict, between 1500 and 3000 people had died, but the government emerged victorious.

However, the violent suppression highlighted the deep divisions within French society.

In the aftermath of the June Days Uprising, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, became an important figure.

In the lead up to the December 1848 presidential election, he promised to restore order, support religion, family, and property, while also addressing workers' needs with vague progressive economic ideas.

Meanwhile, his main rival, General Cavaignac, was associated with the violent suppression of the June Days uprising, which alienated many voters.

Ultimately, Louis-Napoleon won a decisive victory with 74% of the vote, but his presidency led to a more authoritarian regime.

On December 2, 1851, he carried out a coup d'état, during which he dissolved the National Assembly and took up dictatorial powers as President of France.

Exactly one year later, on December 2, 1852, he declared himself Emperor of the French under the title Napoleon III, which began the Second French Empire.

What happened in the German States?

Soon after the initial outbreak of revolution in France, in March 1848, unrest spread to the German states.

The German people called for a democratic government rather than their monarchy.

In Berlin in particular, the Prussian king Frederick William IV faced massive demonstrations that challenged his rule.

So, the Frankfurt Assembly convened for the first time on May 18, in St. Paul's Church (Paulskirche), Frankfurt.

This assembly, which included powerful leaders like Robert Blum, aimed to draft a constitution for a unified Germany without requiring the king.

It was attended by delegates from various German states and hopes were high that this was the first step to a new democratic system.

However, disagreements over the structure of the new state and its boundaries plagued the proceedings.

Ultimately, these internal conflicts constantly hindered the assembly's progress.

Although King Frederick William IV of Prussia initially made concessions to revolutionaries in March, including the promise of a new constitution, he began to rely on the Prussian military to crush uprisings in Berlin, Saxony, and Baden, restoring conservative rule.

For example, when Friedrich Hecker led an uprising in Baden in April 1848, known as the 'Hecker Uprising', which specifically sought to establish a republic to replace the king, his movement was defeated by Prussian government forces near Kandern.

At the heart of the problems was the issue of including Austria in the new German state.

Some delegates supported a "Greater Germany" that included Austria, while others favored a "Lesser Germany" without it.

In March 1849, the Frankfurt Assembly adopted the Paulskirche Constitution, envisioning a unified Germany under a constitutional monarchy.

On the 3rd of April, 1849, the assembly offered the imperial crown to King Frederick William IV, who rejected it stating he would not accept a crown "from the gutter", since it lacked the legitimacy of divine or princely authority.

This refusal dealt a severe blow to the revolutionary movement.

In the light of these failures, the Frankfurt Assembly was dissolved on May 31. Reactionary pro-monarchy forces quickly moved to restore order and suppress any revolutionary activities.

By the summer of 1849, most revolutionary efforts had been quelled. The German states reverted to conservative rule, and the dream of a unified, liberal Germany was postponed.

The revolutions in the Austrian Empire

Meanwhile, the Austrian Empire faced internal strife as Hungarian, Italian, and Czech nationalists sought greater autonomy or independence.

In March, the capital city of Vienna erupted in protests, leading to the resignation of the influential Chancellor, Prince Klemens von Metternich, on March 13.

With Metternich's fall and escape to England, the revolutionary fervor spread rapidly.

Soon after, various ethnic groups within the empire, such as Hungarians, Czechs, and Italians, demanded greater autonomy and rights.

In Hungary, Lajos Kossuth led the movement for Hungarian independence. On March 15, 1848, Kossuth delivered a passionate speech in Budapest, which inspired the Hungarian Diet to declare autonomy from Austria.

By April, the Hungarian army had mobilized almost 180,000 troops to defend its newly proclaimed rights.

However, the Austrian government refused to accept Hungary's demands.

Similarly, in Habsburg-controlled regions of northern Italy, cities such as Milan and Venice rose against Austrian rule.

During the Five Days of Milan in March 1848, Austrian troops retreated from the city on March 22, 1848.

Subsequently, the Venetians declared a republic in Venice on March 22.

To counter these revolts, the Austrian Empire had to divert significant resources and troops, which complicated its efforts to maintain control.

Nevertheless, Austrian troops later returned and retook the city in August 1848.

In Prague, Czech nationalists demanded greater autonomy within the Austrian Empire.

The first ever Pan-Slav Congress was held from June 2 to June 12 and brought together representatives from various Slavic regions.

They sought to promote unity and cooperation among Slavic peoples. However, the Congress's aspirations were soon interrupted by violent clashes in the city of Prague itself.

On June 12, 1848, the Austrian military crushed an uprising in Prague.

Further south, in the Balkans, the Romanian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia witnessed significant revolutionary activities.

Wallachian revolutionaries adopted the Proclamation of Islaz, which demanded political and social reforms.

By October 1848, the situation in Vienna grew more dire. On October 6, a violent uprising erupted in the capital, leading to the death of Austrian Minister of War Theodor Baillet von Latour.

As a result, Emperor Ferdinand I fled the city and left it in the hands of the revolutionaries.

In response, the Austrian military under General Windisch-Grätz, launched a brutal counter-offensive to take back control.

On the 31st of October, Vienna was retaken, and the revolutionary leaders faced harsh reprisals.

Meanwhile, the Hungarian revolution continued into 1849, with Hungarian forces scoring several victories.

In desperation, Austria sought assistance from Russia to suppress the uprising.

Fearing the spread of revolutionary instability into his own lands, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia sent an army of 200,000 troops into Hungary in June 1849.

A combined force of 300,000 Austrian and Russian troops crushed the Hungarian forces in a variety of battles over the next few weeks.

Outnumbered and outgunned, the Hungarian army surrendered at Világos on August 13, 1849, which ended the revolution and reasserted Austrian control.

The 1848 revolution in Italy

In March of 1848, the revolutions reached Italy. Throughout the Italian Peninsula, the desire for Risorgimento, or 'resurgence', became a powerful force.

In the Kingdom of Sardinia, King Charles Albert responded to the revolutionary spirit by declaring war on Austria.

His aim was to unite northern Italy under Sardinian leadership. To achieve this, the kingdom mobilized its forces and achieved initial successes against Austrian troops.

However, at the Battle of Custoza on July 24-25, 1848, Charles Albert's forces suffered a decisive defeat, but Sardinia fought Austria again in March 1849 before finally being defeated at Novara on the 23rd of March 1849.

As a result, King Charles Albert of Sardinia abdicated in favor of his son, Victor Emmanuel II.

Elsewhere, Rome experienced its own revolutionary fervor. In November 1848, the assassination of Count Pellegrino Rossi, a conservative minister, sparked unrest.

Subsequently, Pope Pius IX fled the city, and revolutionaries established the Roman Republic in February 1849.

It was led by figures such as Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Under their direction, the new republic sought to implement dramatic democratic reforms.

However, before it could achieve them, the new government faced immediate threats from foreign intervention.

The French, in particular, were eager to restore papal authority and sent a military expeditionary force to Rome.

By late April of 1849, French troops laid siege to the city and, although Garibaldi and his forces mounted a valiant defense, the French army proved too strong.

After intense fighting, Rome fell to the French on July 3, and was officially occupied on July 4, 1849. The revolution in Italy was over.

By this time, Austria had also crushed the last pockets of resistance and regained control over its lands in northern Italy in August of 1849.

However, the ideals of the Risorgimento continued to inspire many Italians as figures like Mazzini and Garibaldi remained committed to the cause of unification.

Central and eastern Europe

The Revolutions of 1848 also affected Central and Eastern Europe, where nationalistic and liberal movements surged.

For example, in the Polish territories, the quest for independence from Prussian control continued.

Poznań experienced a brief uprising in March 1848, however by April, the rebellion had been suppressed.

The impact of the 1848 revolutions also extended into Transylvania, where Hungarian nationalists aimed to integrate Transylvania into Hungary, but the region's Romanian population opposed this move.

Violent clashes erupted, including the key battle of Sighisoara in July 1849. Austrian and Russian forces decisively defeated them, leading to the reassertion of Habsburg authority.

Why did the 1848 revolutions fail?

By 1849, most revolutionary movements in the various countries across Europe had been suppressed by government forces and had restored conservative rule.

Although the revolutions did not achieve their immediate goals of achieving liberalism, nationalism, and social reforms, they did leave a lasting memory in European politics.

In many states, the ruling elites recognized the need to address some of the grievances that had fueled the uprisings.

Consequently, incremental reforms began to take shape. For example, Prussia implemented limited constitutional changes, which provided hope for more extensive reforms in the future.

And in France, the establishment of the Second Empire under Napoleon III saw a focus on economic modernization and public works projects.

These efforts hoped to stabilize their societies by addressing some of the underlying economic issues.

The desire for national self-determination would become one of the most powerful forces in European politics.

It would eventually contribute to the unification of Italy in 1861 and Germany in 1871.

The revolutions also influenced the spread of new ideologies, such as socialism and communism, which gained traction as alternative visions for society.

In particular, the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which had originally been published in the Communist Manifesto in February 1848, continued to inspire revolutionary fervor for the rest of the 19th century.

In fact, their ideas found a willing audience among those disillusioned with the failures of the 1848 revolutions.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.