What was the Enlightenment and why did it change the world?

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a bold movement swept across Europe, which introduced the idea that you could challenge authority, tradition, and centuries of established thought.

Known as the Enlightenment, it inspired an entire generation of thinkers, scientists, and revolutionaries. They argued that the collection of knowledge was life’s highest pursuit, and the individual—equipped solely with the power of ‘rational thought’—stood at the center of this intellectual revolution.

As a result, kings and religious leaders, who had long been considered divinely appointed to their positions of power, suddenly faced the scrutiny of a range of new political theories.

So, what drove these men and women to reject thousands of years of tradition and how did they create the modern society we know today?

Why the Thirty Years' War undermined the authority of the Church and kings

The Thirty Years' War, which had raged from 1618 to 1648, had been started by religious conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in the Holy Roman Empire as a result of the Protestant Reformation.

However, the conflict quickly evolved into a broader struggle over political and territorial ambitions.

Due to the war’s widespread destruction, the moral authority of the Church gradually came into question.

This is because religious leaders had described the war as a divine struggle, but the horrific scale of violence and suffering eroded the belief that God favored either side.

Importantly, the document which officially ended the war, known as the Peace of Westphalia, made the revolutionary decision that individual rulers could determine the religion their people would follow: a principle known as cuius regio, eius religio.

It was believed that this would avoid any further wars over religious differences.

However, this led to a further decline in the Church’s ability to dictate religious matters across borders.

As a result, religion no longer served as the primary basis for political alliances.

The war also severely damaged the authority of monarchs who had relied on divine right as the foundation of their rule.

Monarchs like Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire had used religion to justify their wars, but the conflict's failure to resolve religious tensions cast doubt on the legitimacy of divine right.

The enormous human and economic costs of the war led to widespread disillusionment with rulers who had driven their nations into ruin.

This led to an increased demand for accountability and the rise of political systems that sought to balance power between monarchs and representative institutions.

The core ideas of the Enlightenment

As a consequence of this weakening of both religious and monarchical authority, the Thirty Years' War opened the door for Enlightenment thinkers to challenge traditional structures of power.

The war had exposed the dangers of mixing religion and politics, and the chaos it caused led to a rethinking of the role of government and the rights of individuals.

Philosophers began to advocate for systems of governance based on reason, natural law, and the consent of the governed, rather than divine will or hereditary rule.

Consequently, the intellectual fallout from the war created an environment in which both the Church’s and monarchs’ unquestioned authority could be scrutinized and reformed.

Thinkers of the time viewed reason as the most reliable tool for understanding the world and improving human life.

They rejected the notion that knowledge came from tradition or divine revelation. Instead, they insisted that individuals could discover truth through rational thought and empirical observation.

This emphasis on reason challenged existing structures of power, particularly the dominance of the Church and monarchies, which often relied on faith and unquestioned authority to maintain control.

As a result, philosophers believed that every person possessed inherent rights and potential for intellectual and moral growth.

Rather than viewing individuals as subjects bound by class, religion, or tradition, Enlightenment thinkers saw them as capable of self-determination.

John Locke's idea of natural rights reflected this belief. According to Locke, people had the right to life, liberty, and property, and governments existed to protect these rights, not to grant them.

The pursuit of liberty was central to the Enlightenment's intellectual project.

Enlightenment thinkers believed that societies could only progress if individuals were free to express their ideas and challenge old assumptions.

New political ideas

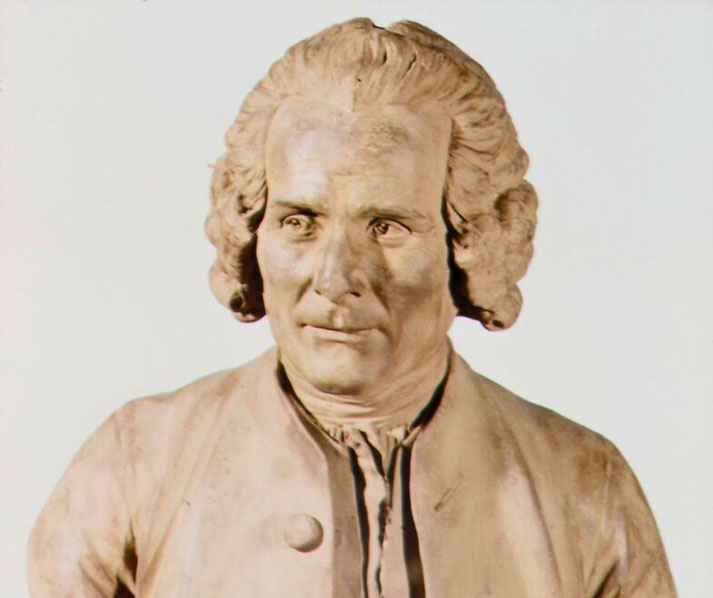

More than anything, the Enlightenment revolutionized political thought. One of the most influential ideas to emerge was the concept of the ‘social contract’, popularized by thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The social contract proposed that governments had their authority from an agreement among individuals to create a society where their rights would be protected.

Hobbes, in his 1651 work Leviathan, argued that in the absence of government, life would be "nasty, brutish, and short", so people in the past essentially agreed to submit to a powerful ruler.

Locke, however, contended that government existed to protect natural rights, and if it failed to do so, the people had a right to rebel.

These ideas laid the groundwork for modern democracy. Locke’s emphasis on natural rights—life, liberty, and property—inspired political movements that sought to limit the power of monarchs and expand the role of the people in running countries.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England and the subsequent Bill of Rights reflected these principles.

Locke’s theories also heavily influenced the American Revolution. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence echoed his belief that governments existed to secure the rights of the people and that unjust rulers could be overthrown.

Human rights, another central concern of the Enlightenment, became a focus as philosophers began to advocate for universal principles that transcended class, race, or religion.

Rousseau’s The Social Contract of 1762 argued for the ‘general will’ of the people, suggesting that legitimate government must reflect the collective interests of its citizens.

Enlightenment political thought also encouraged a reevaluation of monarchy and absolute rule.

Montesquieu, in his 1748 work The Spirit of the Laws, argued for the separation of powers within government to prevent tyranny.

He proposed that power be divided among different branches—executive, legislative, and judicial—each acting as a check on the others.

In fact, this concept of balanced government became a cornerstone of modern constitutional systems, influencing the creation of the United States Constitution and shaping democratic institutions worldwide.

The Enlightenment challenge to religion

The Enlightenment brought with it a sharp critique of organized religion, particularly the power and influence of the Catholic Church in European society.

Thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot attacked the Church for its role in suppressing intellectual freedom and maintaining control through superstition.

Voltaire, in particular, despised religious intolerance, denouncing the persecution of religious minorities and the Church’s heavy involvement in political matters.

Many Enlightenment thinkers, while critical of organized religion, did not reject the idea of a higher power altogether.

Instead, they promoted ‘deism’, a belief in a rational and distant creator who did not interfere in human affairs or violate the laws of nature.

Figures like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin embraced this view, seeing God as a watchmaker who set the universe in motion but left it to run according to natural laws.

Deism allowed thinkers to reconcile their belief in reason with a form of spiritual understanding, which appealed to many who had grown weary of religious dogma yet still sought a moral order.

By advocating for a more personal and rational belief in God, Enlightenment thinkers helped pave the way for secularism and the separation of church and state.

This shift can be seen in revolutionary movements, especially in America, where the First Amendment to the Constitution prohibited the establishment of a state religion.

Enlightenment ideals influenced the development of religious tolerance, as thinkers argued that morality could exist independently of religious authority.

How the Enlightenment led to violent revolutions

In the American colonies, Enlightenment ideas about liberty, equality, and self-government gained popularity in the mid-18th century.

Thinkers like John Locke influenced colonial leaders with his arguments that government must protect natural rights, and that power resided in the people.

By the time tensions escalated between the colonies and Britain in the 1760s, Locke’s ideas about the social contract and the right to overthrow tyrannical governments resonated with many.

The Declaration of Independence, written in 1776, explicitly drew upon Enlightenment ideals, declaring that "all men are created equal" and endowed with "unalienable rights" to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The success of the American Revolution further amplified Enlightenment ideals in Europe, particularly in France.

In the years leading up to the French Revolution of 1789, philosophers like Rousseau and Voltaire openly criticized the oppressive monarchy and the rigid social hierarchy that defined French society.

The French Revolution also drew inspiration from Enlightenment principles in its call for universal human rights.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in 1789, echoed the themes of liberty and equality, arguing that sovereignty resided in the people, not in a monarch.

It proclaimed that all citizens were entitled to freedom of speech, religion, and the protection of the law.

While the American Revolution established a constitutional republic and provided a practical example of Enlightenment ideas in action, the French Revolution took these ideas further, challenging not just political power but the entire social order.

The revolutionaries sought to replace the old structures of power with a new vision based on Enlightenment ideals, even as the process itself descended into brutality.

Was the Enlightenment a good or bad thing?

The Enlightenment, while revolutionary in its ideals, faced significant criticism for its Eurocentrism.

Many Enlightenment thinkers assumed that European culture and ideas represented the pinnacle of human achievement, often dismissing the value of non-European societies.

Philosophers like Voltaire and Kant, despite their progressive ideas, sometimes portrayed non-Western cultures as primitive or inferior.

This narrow focus on Europe limited the Enlightenment's claim to universalism, as it often failed to recognize the contributions and complexities of civilizations outside the Western world.

Also, it tended to exclude women from the intellectual and political debates of the time.

While philosophers championed reason and individual rights, they often restricted these ideas to men.

Thinkers like Rousseau, in his work Émile, argued that women’s education should focus on their roles as wives and mothers, to reinforce traditional gender roles.

Mary Wollstonecraft, in her groundbreaking A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), directly challenged these ideas, arguing that women were rational beings deserving of the same rights and education as men.

Furthermore, although it advocated for human rights, many Enlightenment thinkers failed to condemn slavery or the exploitation of colonized peoples.

While the movement laid the intellectual groundwork for later abolitionist efforts, key figures such as Locke and Jefferson owned slaves.

Enlightenment ideals of liberty and progress often coexisted with the brutal realities of colonialism and racial discrimination, particularly in the Americas and Europe.

Finally, critics have also pointed to the Enlightenment’s overreliance on reason as a serious limitation.

While the movement celebrated human rationality, it often downplayed the importance of emotion, tradition, and spiritual beliefs in human life.

Figures like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, though an Enlightenment thinker himself, criticized the movement’s focus on reason alone, arguing that it ignored the emotional and communal aspects of human existence.

Rousseau believed that the Enlightenment’s emphasis on individualism risked alienating people from their communities and cultural traditions.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.