The revolutionary WWI convoy system that outsmarted the deadly German U-Boats

Imagine the dread that spread across the Atlantic as merchant ships vanished beneath the waves, torn apart by the silent hunters of the sea. German U-boats stalked the waters and sank Allied vessels without warning.

By 1917, the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare meant no ship was safe, and losses mounted with terrifying speed. Could the Allies continue to fight a war if their ships never made it across the ocean?

With their backs to the wall, they needed a new strategy—one that could not only defend the merchant fleet but also restore hope in a war spiraling toward disaster.

The devastating German U-Boat menace

By early 1917, German U-boats had sunk an alarming number of Allied merchant ships, with over 1,000 vessels lost between February and April alone.

Merchant ships were easy targets, and shipping losses skyrocketed. An average of 25 percent of British-bound merchant vessels were sunk every month.

These staggering losses jeopardized Britain's ability to import food, fuel, and raw materials.

To address this crisis, the British government reconsidered the defensive strategies it had in place.

Lloyd George, Britain’s Prime Minister, advocated for the adoption of a convoy system to counter the deadly efficiency of the German submarines.

However, many, including senior figures in the British Admiralty, believed that convoys would make merchant vessels easier targets for U-boats by grouping them together.

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe in particular worried that U-boats could attack convoys en masse, and cause devastating losses.

For months, this view dominated the thinking of British naval planners, who favored individual ship movements over the idea of convoys.

There were also logistical concerns about whether there were enough escort ships to protect large convoys.

Britain’s fleet of destroyers, sloops, and corvettes had been stretched thin by other naval commitments.

Organizing and coordinating the movement of dozens of merchant ships in a single convoy seemed daunting, as any breakdown in communication could lead to chaos.

In addition, the navy feared that convoys would slow down shipping, reducing the overall volume of goods transported and causing delays in vital supplies reaching Britain.

Eventually, the sheer scale of merchant losses forced the Admiralty to reconsider.

By early 1917, shipping losses from U-boat attacks had reached unsustainable levels.

Lloyd George, Britain’s Prime Minister, became a vocal advocate for the convoy system, convinced it was the only solution to the crisis.

However, it took significant pressure from the government to overcome the opposition within the navy.

How the WWI convoy system worked

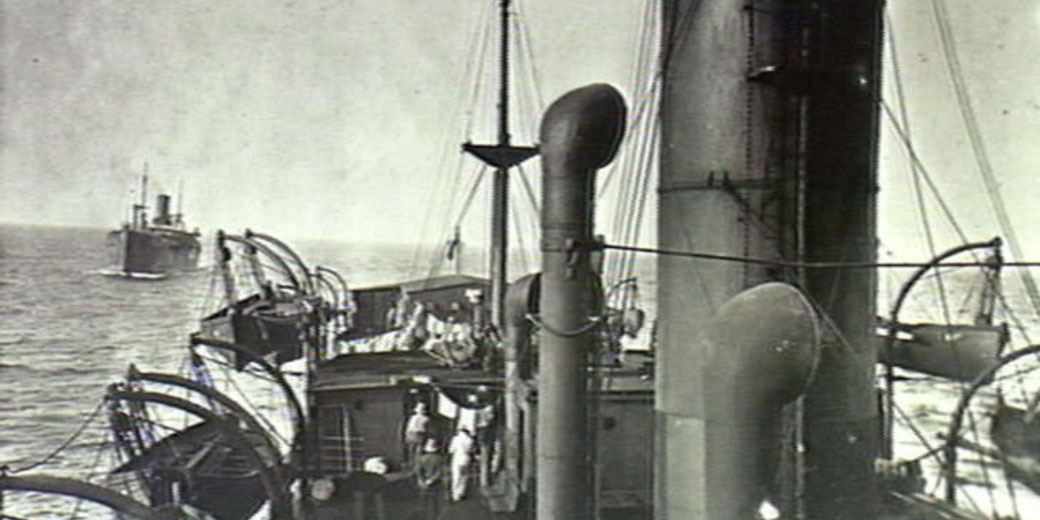

Prior to the introduction of convoys, merchant ships had sailed individually and were easy targets for submarines.

Now, merchant vessels were grouped together into convoys, often numbering anywhere from 20 to 50 ships.

These convoys traveled in tightly controlled formations, with ships maintaining fixed positions to avoid confusion or collision.

The lead ship, known as the commodore’s vessel, guided the convoy along pre-determined routes.

Each ship had to follow its exact place in the formation, and any straying from the convoy was considered dangerous.

To protect these convoys, naval escorts accompanied them on their journeys.

Destroyers, the most common escort ships, were equipped with depth charges and fast engines, allowing them to chase down and attack submarines.

In addition to destroyers, sloops and corvettes often reinforced the escort groups, providing extra firepower and defense.

Also, at specific intervals, escort ships would rotate in and out to ensure that fresh vessels accompanied the convoy as it passed through dangerous waters.

On approach to Allied ports, air support sometimes joined the escorts.

The convoy system relied on several key tactics and technologies to outmaneuver German U-boats.

One of the primary tactics used was zigzagging, where ships altered their course at random intervals to confuse enemy submarines.

U-boat commanders depended on predicting the path of their targets to launch accurate torpedo attacks.

With zigzagging, merchant ships made it much harder for submarines to line up a direct shot.

In addition, at night or in poor visibility, convoy commanders used a tactic called ‘darkening ship’, where all lights were extinguished to make it difficult for U-boats to spot their targets.

This tactic reduced the effectiveness of the submarine’s visual targeting and allowed convoys to move through dangerous areas with greater stealth.

Was the convoy system successful?

In June 1917, when the system became fully operational, fewer than 2 percent of ships in convoy were lost to U-boats, compared to nearly 10 percent of unescorted vessels.

To maintain the flow of goods, the British government prioritized critical cargoes such as grain, coal, and munitions.

Convoys allowed these valuable resources to be transported across the Atlantic, from North America to Europe, where they sustained both civilian populations and military operations.

As a result, Britain avoided the famine and fuel shortages that could have crippled the war effort.

In fact, by the end of 1918, nearly 16,500 ships had traveled in convoy, with only 150 sunk.

This level of protection allowed the Allies to maintain the steady flow of supplies necessary to wage a global conflict.

Moreover, the convoy system ensured that trade routes remained open, preventing economic collapse.

Without it, the loss of merchant ships would have brought transatlantic commerce to a virtual standstill.

How the convoy system changed naval warfare

The convoy system developed during World War I successfully demonstrated that grouping merchant ships under the protection of naval escorts could effectively counter submarine threats.

So, during World War II, when German U-boats once again targeted Allied shipping, the convoy system was immediately reintroduced.

This time, it was adopted from the outset, avoiding the initial hesitation seen in World War I.

Although, the convoy system had now evolved to include new technologies and tactics.

Radar and sonar allowed for better detection of submarines, while aircraft carriers escorted convoys to provide air cover over longer distances.

In addition, the introduction of anti-submarine warfare tactics, such as 'hunter-killer' groups, allowed escort ships to be more aggressive in tracking and destroying U-boats.

As a result, the convoy system became an essential part of Allied strategy throughout the Battle of the Atlantic.

Even after World War II, navies continued to incorporate convoy tactics into their strategic thinking, particularly during the Cold War.

The fear of submarine warfare remained prominent, and the development of nuclear submarines made convoy defense even more critical.

In modern naval operations, convoys continue to be used to protect shipping in areas threatened by piracy or conflict.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.