The greatest sea battles of World War One

When most people think about World War One, they think about land warfare, involving trenches, bayonet charges and tanks.

However, before the war even began, most military strategists believed that any future war would be won or lost on the sea.

Why countries focused on navies before the war

The world's superpowers had focused on developing the best battleships in preparation for war.

Britain and Germany, in particular, had engaged in a naval arms race: Britain had the world's largest navy, while Germany wanted to compete with them.

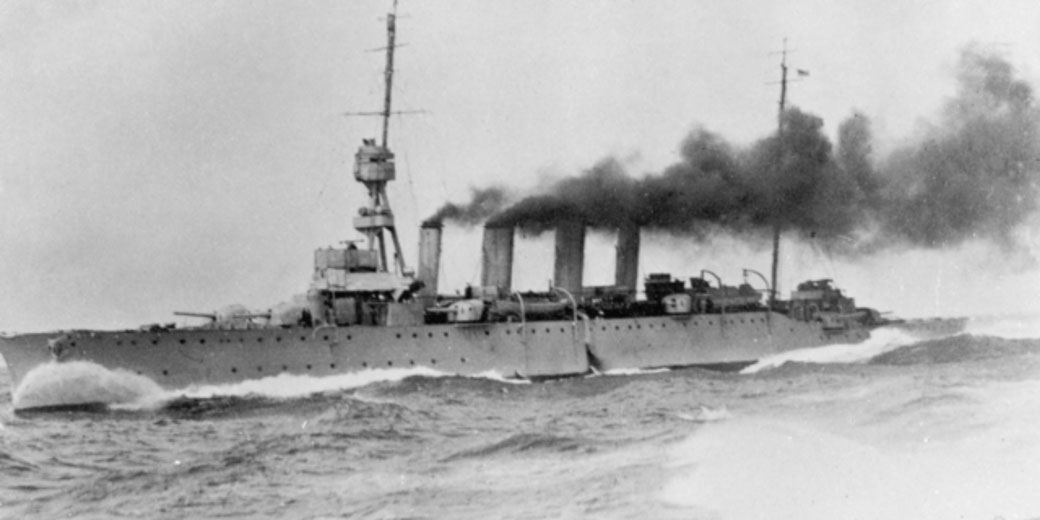

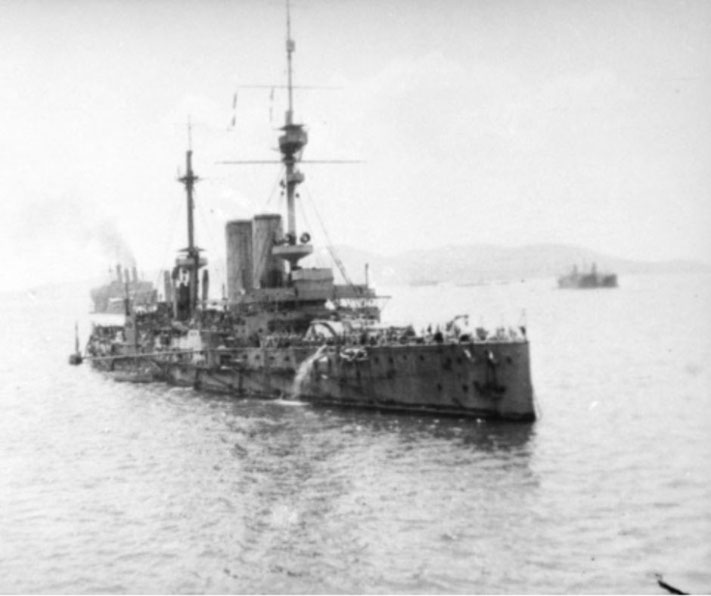

The most advanced battleship design at the time was called the 'dreadnought'.

Dreadnoughts were a revolution in ship design: they were fully metal ships, with massive gun arrays on their decks.

More importantly, dreadnoughts were characterized by their uniform, all-big-gun main battery and steam turbine engines.

This made them much faster and more powerful than older battleship designs.

When the first dreadnought was made by Britain, no other ship in the world could sink it.

Encouraged by this fact, Britain built many more dreadnoughts, while Germany rushed to have as many of its own as possible.

However, by the time WWI had begun, no-one had actually used them in battle, and all ship commanders had to 'learn on the go'.

War begins

At the start of World War One, Britain used its larger numbers of ships to control the oceans around Germany.

Most importantly, it blockaded the ports of Germany and its allies.

Such blockades prevented trade ships from reaching these countries with vital supplies of industrial materials and food.

By starving the German population and limiting the number of weapons they could build, Britain was limiting the effectiveness of their enemy's armies.

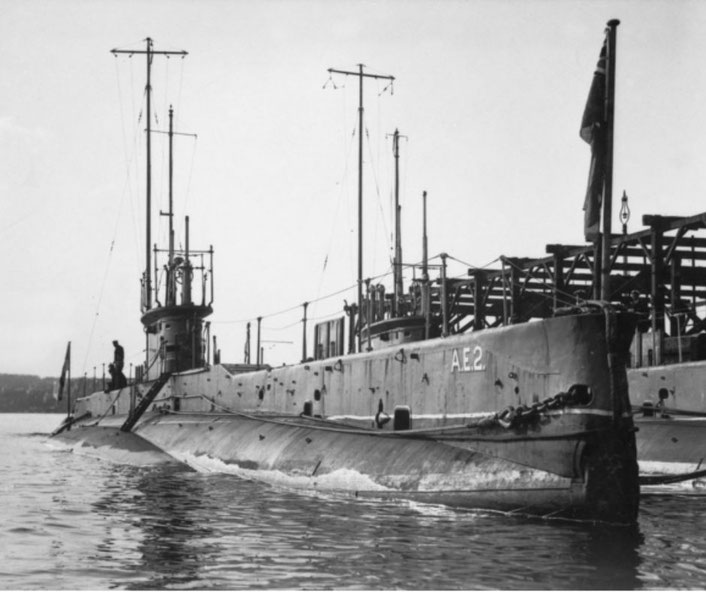

To counteract the trade blockade, Germany relied upon another new technology: submarines. In particular, German submarines were called 'U-boats'.

Before the outbreak of the war, no-one had yet developed an effective defense against submarines, and they could sink a multi-million-dollar battleship with a single torpedo.

For example, in September 1914, one German submarine U-9 that sank three British cruisers.

As a result, ship commanders became terrified of sending their expensive dreadnoughts out of the harbour in case a U-boat sunk them.

For the first two years of the war and into 1916, Britain developed a range of countermeasures to try and stop the U-boat menace.

This included minefields, nets, depth charges and scouting patrols, but they were not very effective.

As a result of the fear induced by submarines, there were no major naval battles during the first half of the war.

While there were minor skirmishes, such as the Battle of Heligoland Bight and the Battle of Dogger Bank, these only involved cruisers and destroyers, rather than the prized dreadnoughts.

However, both sides still believed that if they could get into a fight with the other side's navy, they could have a decisive victory and win the war.

What made this difficult, though, in order to get into a battle, each side had to entice the other to sail their fleets out of their harbours.

It is important to note that navies of other nations, such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, France, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, also participated in naval engagements during the war.

However, it was often on a smaller scale compared to the British and German fleets.

The Battle of Jutland

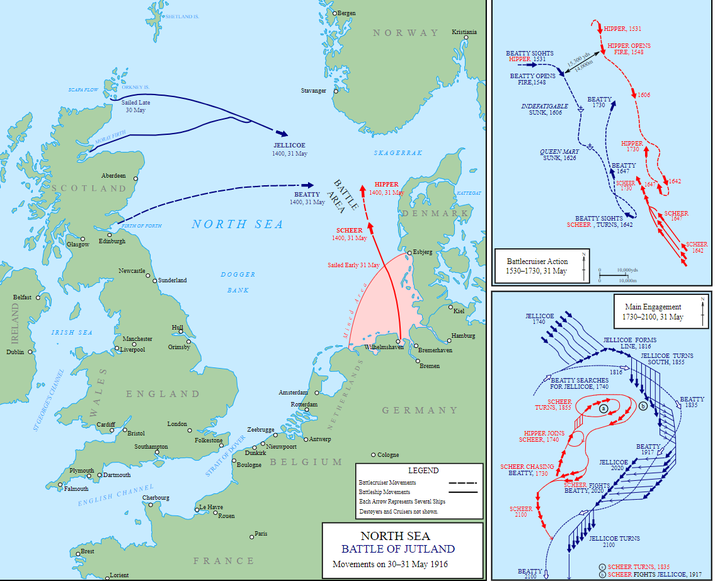

Finally, an opportunity to fight a major naval engagement with dreadnought fleets came on 31 May-1 June 1916.

The British navy was alerted to the presence of German ships in the North Sea, near Denmark, and sailed out of the harbour.

The British Grand Fleet was commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, while the German High Seas Fleet was led by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer.

The two massive dreadnought navies would clash in the Battle of Jutland

In this engagement, the German fleet had fewer ships, but the British fleet suffered the first casualties by losing two ships early.

What quickly became evident is that the guns on the dreadnought ships on both sides were so powerful, and could shoot their shells from so far away, that both fleets rarely saw each other during combat.

The ensuing gun battle lasted all day and all night. By morning, both fleets returned home, suffering significant losses.

The British Grand Fleet lost 14 ships, including three battlecruisers, three armored cruisers, and eight destroyers. An estimated 6094 British sailors were killed.

On the German side, the High Seas Fleet lost total of 11 German ships, including one battlecruiser, one pre-dreadnought battleship, four light cruisers, and five torpedo boats.

Also, around 2,551 German sailors lost their lives in the battle.

Despite these very heavy losses, the outcome of the Battle of Jutland was inconclusive.

Both sides claimed that they had achieved a victory, but neither fleet dealt a decisive blow against the other.

For the British, the loss of several battlecruisers raised questions about their design and vulnerability.

In contrast, the German fleet, although suffering fewer losses, did not manage to break the British naval blockade.

As a result, Germany didn't allow its fleet to leave harbour for the rest of the war, handing control of the North Sea to its enemy.

Surprisingly, the Battle of Jutland would be the only significant naval battle of the war.

It showed the irrelevance of battleship combat to the wider war.

Unrestricted submarine warfare

Following the Battle of Jutland, Germany returned to focusing on submarine warfare.

It believed that if it could simply sink the opponent's ships, it would no longer have to risk its own in battle.

So, on the 1st of February 1917, Germany announced 'unrestricted submarine warfare', which meant that they would sink any ship they considered to be helping the Allied cause.

This included merchant or trading ships, particularly in the Atlantic Ocean.

By doing this, Germany hoped to weaken Britain's position in the war, similar to how Britain's blockade of Germany's ports was weakening them.

In fact, the British naval blockade had led to severe shortages in Germany. Some estimates state that it contributed to the deaths of around 400,000 German civilians due to starvation and malnutrition by the end of the war.

The result of unrestricted submarine warfare was catastrophic for British shipping.

Huge numbers of merchant ships were sunk by U-boats. This meant that the British government had to limit its use of resources for the war.

To minimize the damage caused by the German submarines, Britain and its allies developed the 'convoy' system.

A convoy was a group of ships that worked together to protect merchant shipping.

Warships were sent to escort trade and passenger ships by detecting and shooting at U-boats.

By the end of 1917, this new system had effectively neutralised the U-boat threat and Britain had control of the seas once more.

Ultimately, the Allied naval blockade and control of the seas contributed to the final defeat of the Central Powers.

However, when the war finally ended, there had been significant technological advances in naval warfare.

Countries had quickly learnt how to incorporate wireless communication, improved gunnery and fire control systems, and introduced aircraft for reconnaissance and bombing missions.

These lessons would become an important element in future conflicts, including the Second World War.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.