What was the Industrial Revolution?

The Industrial Revolution was a period of time that began around 1760 and continued into the 19th century that resulted in significant changes in transport, manufacturing and power production that changed the modern world forever.

This revolution took place in Britain due to its easy access to coal deposits and a culture of experimentation.

Background

Before the 18th century, British manufacturing, that is the making of items, only existed on a small scale.

Clothes production mostly occurred in people's own homes or cottages. As a result, it was referred to as a 'cottage industry'.

For most of British history, people made their own clothes, shoes, and household items.

This work was usually carried out by women in the home, and, on some occasions, they could sell any excess items to other members of their community.

By the dawn of the 18th century, a series of new ideas and technologies began a rapid transformation of the creation of products.

Following a revolution in agricultural practices, which increased the life expectancy and population size of Britain, people began moving from rural areas into large cities to find work.

At the same time, the creation of new factories required a lot of workers.

Therefore, the factories hired many people at low wages to run the new factory systems.

Steam power

During the Middle Ages, most sources of power were based upon nature: wind power, or water wheels.

As a result, these power sources were unreliable and would change throughout the year.

Some people tried to use more consistent sources of power, like horses, to create machines to mill flour, but the machines were slow.

Then, in the early 1700s, several inventors started experimenting with steam, produced from heating water, to create more reliable power sources.

Around 1712, a man named Thomas Newcomen created the first steam-powered engine.

It was initially used to pump water out of deep coal mines. However, Newcomen's engine was too large and was hard to move to new locations, so others continued to improve upon his design.

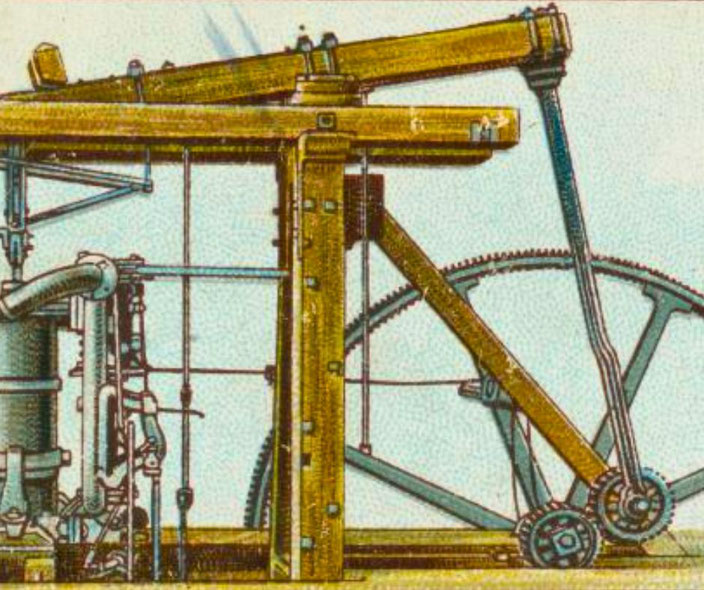

A Scottish engineer, James Watt, and an English manufacturer, Matthew Boulton, made significant improvements to existing steam engines and, at the end of the 18th century, made one of the most efficient systems available.

It used less coal to produce more power and required less repairs. The Boulton and Watt engines were sold to factories all around the world.

These new steam engines created a far more consistent source of power so that machines could now be run all day and night, as long as they had a constant source of coal to run their fires.

As a result, many steam engines were built close to coal mines.

Textile factories

With the creation of consistent power sources, other inventors began improving upon the old cottage industry for cloth creation.

In 1769, Richard Arkwright created, what he called, the ‘water frame’.

This was a powered machine that could spin cotton thread by itself. Following this, James Hargreaves created a ‘spinning jenny’, which did the same thing, but on a much larger scale.

In the 1780s, Edmund Cartwright created the 'power loom', which was able to mass produce cheap cloth much quicker than had been possible before.

When factory owners connected steam engines to these machines, the quantity of cloth produced escalated rapidly.

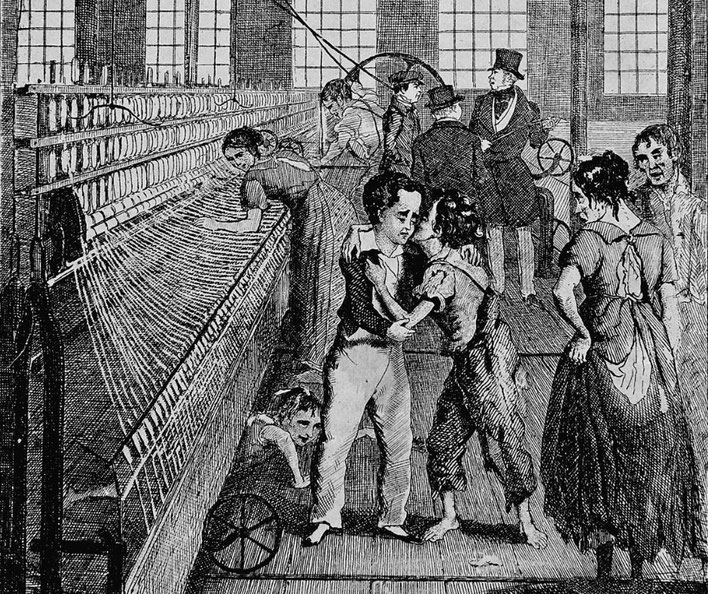

Large factory buildings with rows of textile machines could now produce products around the clock.

If factories were designed well enough, just one steam engine could power dozens of machines at a time.

So many machines running at once for so long needed constant repairs. As a result, most factories needed to hire teams of people to supervise textile production.

Factory owners tried to keep costs down by paying the lowest cost possible for workers.

Children became a common employee option, not only because they could be paid less, but also because they were small, they could easily fit inside machines to fix them.

Transportation

As cloth production increased, the need to transport the new products to shops also increased.

Likewise, as factories needed more coal to fuel their steam engines, owners wanted a quicker way of moving it to their businesses.

To solve this problem, new inventors began exploring ways of improving the aging, dirt-road systems that had existed in Britain for millennia.

One of the first solutions was to use the river systems that crossed Britain. By building long, thin boats, they could move goods quicker than the roads allowed.

Unfortunately, rivers rarely connected to each other.

So, engineers began constructing artificial rivers, called canals, to connect natural river systems and major cities.

One of the most famous examples of this was in 1761, when the Duke of Bridgewater connected his coal mine at Worsley to the city Manchester with a new canal.

As a result, Manchester became one of the most important cities for industrial production.

By the year 1815, an estimated 2,000 miles of canals were created throughout Britain.

With the increased income from canals, towns also wanted to improve the road system to cash in on the transport revolution.

Local communities applied for a government initiative called the ‘Turnpike Acts’.

This gave authorities the permission to build new roads that could be paid for by charging a fee to those who travelled on them.

With more efficient modes of transport, sources of power and manufacturing technologies, Britain was able to become the wealthiest trading power in the world.

The industrial revolution was one of the main causes of the British Empire's global dominance throughout the 18th century.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.